Reminiscences

of my 60 years in South America | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

From

Schoolboy to Apprentice | |||||||||||||||||||||||

"we're

shut.. so get out" | |||||||||||||||||||||||

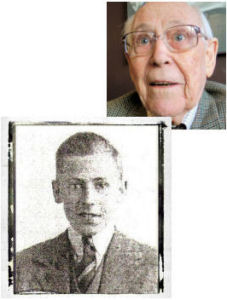

Cranleigh School, Surrey, England,1931 It was the start of the summer term. A rather small boy had been called to the Headmaster's study. Inside, the Headmaster was pacing back and forth, a sheaf of papers in his hand. The boy entered. The Headmaster stopped pacing. The Headmaster was a tall man. He stared at the boy looking down upon him from his height, his bushy eyebrows in an ominous frown. Suddenly

he waved the papers in his hand as if to blot out all sight of the little boy

standing in front of him. His face turned red as he bellowed Without pausing for breath, the Headmaster continued "Your Spanish teacher reports that if you studied Spanish for a hundred years, you would never learn to speak it." Pulling a sheet of paper from the bunch in his hand, he shouted "Look what your Form Master writes. 'This boy has had the audacity to write down in his Latin Translation 'The messengers came down with the flight of wings and played hornpipes with their feet!' "You must be a perfect idiot!" The boy paled visibly. Then he remembered that he had been stuck for the translation of the word 'gramibus'. Somehow he had associated it with the word 'gramophone' but of course there were no gramophones in Roman times but they did have 'hornpipes'. He looked at the Headmaster out of the corner of his eye. He wondered where all this was going to lead. He had never seen the Headmaster look so angry. Would he be canned or expelled or what? He was conscious that the Headmaster was speaking. "……and where did you get that crazy idea that the Order of the Bath was a law that everyone had to have a bath on Friday nights?" There was a dead silence. The boy felt that no reply was needed. The Headmaster turned to stare out of the window. The boy fidgeted and looked down at his feet. Perhaps the interview was ended. Should he creep out. The Headmaster turned and in a very calm and steady voice, pronouncing each word as though to make it's meaning crystal clear said "Other Headmasters would probably wash their hands of you but your parents have no doubt made great sacrifices to send you to this school in order that you should pass your School Certificate. I will not defraud them. You will no longer learn Greek or Spanish. Instead you will concentrate on the basic minimum subjects for the School Certificate. Each afternoon you will report to me, here, and I will set lessons which you will do in the Reading Room. You will not be disturbed by anyone or anything. Do you understand? I don't care if you never play another game of rugby or cricket but by Heavens I am going to see that you pass your School Certificate. Now go and get out!" Hurriedly the boy left the room. Phew! Lucky it was not worse. He had never been enthusiastic about learning. His parents had sent him to school to learn. They paid the teachers to teach him. Whilst he was not prepared to go out of his way to help them in their task, if they actually succeeded in teaching him something, he would respect them for it and might even learn something. The remedy put in place by his Headmaster worked. Latin, French, Maths, History and Geography were rammed into him. When the exam results were published in the newspapers, he had passed! On the last day before the end of term when he was leaving the school for good, he went up to the Headmaster to say goodbye. The Headmaster smiled at him, put his hand on his shoulder and said "Well, my boy, now you go out into the wide world. I hope that the School has taught you something. It is now up to you. Best of luck and Heaven help you." January

1932 He was full of optimism. He had passed his School Certificate

Now to find a suitable place for his talents. He scanned the advertisements in

the newspapers. He wrote to firms offering places for Assistant Managers, Accountants,

Directors, Company Secretaries and even Consultants. With each letter he enclosed

his CV neatly written in his best handwriting. These included He

liked that last bit. A little Spanish could cover a multitude of sins. Working for nothing Timidly I asked "What salary are you going to pay me?" The man looked at me. Then he shouted "Pay you. You don't know anything, You will pay us two shillings and sixpence per week until you are competent. Then we will talk about wages" I was stunned. That evening I told my father. He said "My son. Take it. It is a job and be thankful." I duly reported for work. I sat at a high desk. Alongside me was a young lad with two large books in front of him. He was entering some invoices or something into one of other of the books, then passing the papers on to me and I had to file them in one of two folders. A few days later I suggested that he gave me one of the books to enter papers into and so we could do the work faster. On Friday the head of the department came over and asked what I was doing. I told him. On the following Monday, the other lad wasn't there. The head of the department said to me "From now on you will enter up both books and do the filing. Incidentally, from next week, you will receive five shillings per week wages."

Upon joining the staff of the Booth Steamship Co I was now earning about £1.0 per week. Obviously I could not afford to live by myself so, in return for living at home, my father gave me to understand that henceforth it was up to me to pay my own expenses. He suggested that I pay my mother six pence a week towards my food. Mother bought me a navy blue overcoat and bowler hat so at least I could start off well dressed as I already had a new pin-striped suit. With the help of my father, we worked out how much I needed for my fares, lunches which I calculated as 9d per day and 3 pence for sandwiches on the Saturdays when I played hockey. Most Wednesdays, my father would invite me to have lunch with him so I used the 9 pence which I thus saved, to take the bus home in the evenings, the fare was one penny , to save me the walk of about one mile. After allowing for a little entertainment, fares when playing hockey and the occasional cinema, I found I could save up to two shillings a week which I placed in a Post Office Savings Account for use on my holidays or for extra expenses. My first job in the office was as office boy and messenger. It was my duty to take the mail to the Post Office, deliver letters to firms in the city and collect letters which had been typed and take them to the departments concerned. After 6 months I was transferred to the Cables Department where I learnt to code and decode messages from the North Brazil Agencies. I quickly became very efficient at coding and soon could read many messages without having to decode them. When, later, I was promoted to the Passengers Department, one of my jobs was to take the passports of the Tourist Passengers to the Brazilian Consulate to obtain the necessary visas. One day I arrived at the Consulate just before closing time. As I entered the offices, a clerk called out "We're shut so get out." As I made no motion to leave, he shouted "The Consulate is closed, do you understand?" I dug my heels in and replied "I'm not leaving without the passports and I'm staying right here." At that he picked me up and literally threw me out of the door and locked it. I was furious so back at the office I complained to the Manager about the treatment which I had received. The Manager thereupon phoned the Brazilian Consul General and lodged an official complaint, The result was that I was invited to return to the Consulate where the Consul General himself showed me in. After profuse apologies, he gave me a cup of tea whilst he stamped all the passports and handed them back to me. There were times, I believe, when the firm sincerely doubted the wisdom of having employed me. I recall two such incidents very vividly. As a new Junior, it was one of my tasks to take tea in the afternoons for the Directors. I was given precise instructions as to how to lay the clean white tablecloth exactly 15 inches from the edge of the table, place the teapot on the right, then the milk jug followed by the sugar basin on the left. Four cups and saucers with teaspoons were to be placed in a row in front so that the Chairman, Mr Charles Booth, could serve the tea. One afternoon, as usual, I picked up the large tray with all the tea things from the telephone operator who made the tea and carried it to the door of the Boardroom. The door was shut. It was a warm afternoon and the Boardroom windows were wide open. Pushing the door open, I entered. At that moment, the wind caused the door to slam shut. As it did so, it caught the edge of the tray and the milk jug fell over. The table cloth was sopping wet. I laid the tea things out but without the table cloth. When I went to take away the tea things, Mr. Booth remarked "You forgot to lay out the table cloth." "I'm sorry, Sir, but unfortunately the door hit the edge of the tea tray and the milk got spilt on to the table cloth. As the cloth was wet I couldn't put it on the table as it might spoil it." "Quite right, my boy, it was an accident. Don't worry. It was fortunate that there was still some milk left." I hesitated, then blurted out " There wasn't any milk left so I poured what was left on the tray in to the jug and then I wrung the rest out of the teacloth." I saw from his face that I had said the wrong thing so hurriedly left the room. I was very keen on playing Hockey at that time and apart from playing for Oxton Hockey Club in Birkenhead where I was Captain of the 3rd Xl, on Sunday afternoons myself and a number of other lads and girls, all good players, would gather on the shore at Hoylake in front of the lifeboat station for a game on the sand. These were very popular and many people came to watch. We even held matches against a similar team in Wallasey. The

next occasion that I blotted my copybook was when I was in my second

year. As mentioned above I played Hockey for Oxton Hockey Club. On Saturdays as

I could not afford to have my lunch at a restaurant or café, I would bring

some sandwiches to the office. As soon as everyone had left, I would lock the

main door, then go into the Chairman's office where he always had a warm fire

in winter and, sitting in his armchair, put my feet up, read his newspaper and

eat my sandwiches in peace. Next Saturday, as I was eating my sandwiches, I heard a banging and shouting. I took no notice. Monday morning, I was called to Mr. Booth's office. He did not seem to be in a good mood. "Did you by any chance lock the door of the private lift on Saturday?" I could not tell a lie. "Yes, Sir." "Why?", he asked. "I didn't want you coming in to disturb me." He then proceeded to tell me that such goings-on were not tolerated in an office. That henceforth I was to eat my sandwiches OUTSIDE the office. Convinced that he was deadly serious about this, on subsequent Saturdays I took the precaution of sitting close to the front entrance to the office and hidden from view in such a way that I could see Mr. Booth should he walk out into the main office from his private lift but he would have difficulty in seeing me. If necessary I could always nip out of the front door before he could come close enough. In spite of the depression, Charles Booth had much faith in the future and in 1931 he ordered the building of a new passenger liner with a certain amount of cargo space, the "Hilary", to be built by Cammell, Laird & Co in Birkenhead. She was to supplement the "Hildebrand", a luxurious passenger vessel built in 1911 for the famous "1000 Miles up the Amazon" tourist trade. Alas! the business climate was not appropriate and in 1932 the "Hildebrand" which had been moored at Queens Dock, sailed for Milford Haven where she was laid up. In 1934 this lovely ship was sold for scrap. A list of furniture and fittings was pinned up in the office in case any of the staff would like to buy something. I treasured the ship bell but at £10 it was way beyond my means so I decided upon a wash basin outfit. This consisted of a tall narrow piece of furniture. At the top was a metal tank to be filled by a steward each morning with cold fresh water. Beneath was a mirror and small ledge to hold a tumbler, toothbrush etc. Beneath this was a flap which opened revealing a wash basin. A tap allowed water to flow from the tank into the basin. When finished washing, the flap would be shut and the dirty water spilt into another metal tank underneath. I put my name down for it for two shillings but it was pointed out to me that the bottom would need to be cut level since it was built to accommodate the cant of the deck! As a result I settled for a lovely mirror in a mahogany frame for 6 pence. My most interesting job was in the Freight Departments where I had to calculate the freight rate of many exotic cargoes. This entailed working out such calculations as 2 Tons, 3 hundredweight, 1 quarter, 12 lbs, 9 ounces @ 243 shillings and 6 pence per ton. The firm did provide a calculating machine which consisted of a barrel with numbers from 1 to 10 in 10 rows. One had to move small levers to the correct number, then turn a handle at the side by the number one was multiplying by. However, like computers today, they are only accurate according to the information fed into them. Having made one mistake which was pointed out to me by the Head of the Department, henceforth I always checked my results by hand, a practice which I continue to do even today. Charles Booth did not fully believe in telephones. He used to say "How do you know that what you say into the phone, comes out at the other end? Always confirm your conversations in writing." When invoices had been made out (all freights both inward and outwards were paid in Liverpool) I had to take the invoices round to the various shippers or importers which gave me a good insight into the streets of the city. From time to time I had to visit Queens No.2 dock which was where all the Booth ships lay. I would usually take the Overhead Railway there but if there was a Hackney Carriage [horse drawn taxi ed] when I came out of the dock gates, I preferred to return in style in a horse drawn cab [taxi]. England in the thirties was in the grip of the Great Depression. Cargoes were few and far between and more and more of the Booth ships were laid up or sold for scrap. The pride of the fleet, the s.s."Hildebrand" which was laid up for a long time in South Wales was finally sold. At Christmas time, Mr Booth would come into the main office, wish each Junior a Merry Christmas and hand him a crisp brand new £1 note, a princely sum for we Juniors at that time. Mr Charles Booth used to take a great interest in the welfare of his employees and especially the Juniors. We were encouraged to go to Night School and he would pay the fees and if we passed our exams would give us two shillings and six pence . I went to Night School in Hoylake to learn Bookkeeping, English and Shorthand. I still do not know why I opted for this last subject and I was certainly no good at it. Charles Booth's eldest son, John Booth, came into the firm as Manager and immediately insisted that everyone improve their English. No more "ults" and "Insts" and remember "I before e" etc. Dictionaries were provided and if we were not sure how to spell a word, then we had to look it up. Any letter which contained a spelling mistake, meant a ticking off by him as though we were still at school! We juniors had our lunch break from noon till 1 pm sharp. The seniors, that is the permanent staff, went out at 1 pm and returned anytime after 2 pm, often as late as 2.20 pm. During this time, we Juniors would play games such as Dover Patrol or play with yo-yos. Due to the lack of cargoes, more and more ships were laid up and sold. Nevertheless , with an eye to the future, Mr Booth ordered several new vessels. The "Basil", "Benedict" and "Boniface" were launched between 1928 and 1930 and the luxury liner "Hilary" was launched in 1931 to replace the "Hildebrand" which was too large for the few tourists and passengers. I recall one day in 1933. The "Hilary" was moored at Princes Landing Stage prior to sailing. John Booth told everyone who could be spared to go on board and keep walking around the decks to make it look as though the ship was full of passengers. When the call came "All those not sailing, please go ashore", it was as though everyone was abandoning ship! By 1935, conditions were improving and cargoes of Brazil nuts began to arrive. These were shipped in bulk and Brazilian labourers, known as 'trimmers' were employed to constantly turn over the nuts during the voyage. One day I managed to scrounge a couple of nuts when I went aboard the "Boniface". They were lovely and juicy. However, the next day I learned that new Brazil nuts are laxative! In 1935 a new part cargo, part passenger ship, the "Anselm" was launched at Dumbarton. I was thrilled to see her as she arrived in the Mersey. By the time that I sailed for Brazil, the Booth fleet consisted of only 9 vessels. When my salary was increased to £80 per annum, I was politely informed that henceforth the money would be deposited in a savings account with Alfred Booth & Co. Ltd, the firm's investment office, where it would earn 5% interest per annum. It was RECOMMENDED that I did not draw out all the money at once but only so much as I needed. There should always be some money over at the end of the month! In this way we Juniors were taught to be thrifty! At the end of the year I was horrified to be told that money had been deducted from my account for Income Tax! I considered this to be downright robbery! How dare the Government deprive me of my hard earned savings to pay for their pleasures! Discovering that I could reclaim the money since I didn't earn enough to pay income tax, I proceeded as fast as I could to the Income Tax Office in India Buildings. An officious gentleman wanted to know what I wanted. "I wish to reclaim Income Tax illegally deducted from my Savings Account" He handed me a form so I returned it. "I don't understand such forms. Please be so kind as to fill it out for me." We went into a private room where he asked me all sorts of ridiculous and impertinent questions such as "Are you married?, When were you born? How much do you earn" etc. When he had finished, he asked "And how much income tax are you claiming back? "Eight pence", I replied. I thought he was going to explode. "What! You mean to say I have been wasting almost an hour of my time, just for 8 pence?" "Sir, I answered, "it is not the amount but the principle. If I don't claim back 8 pence, when I need to claim back £1000 you can retort 'you didn't claim back 8 pence so you cannot claim back £1000 now ' He had no answer for that and asked the number of my bank account. " I have no bank account. I will take the money in Cash". In the end we settled for a cheque to be sent to my father. During my last year, I had the task of entering up one of the ledgers of the Brazilian Agencies. One day I entered up something wrong. The Chief Accountant noticed this and said "Take it out immediately." Taking him at his word, I ripped out the page! The Chief was not very pleased. Towards the end of my apprenticeship, one of the overseas staff from the Manaus office came home on leave. He confided to me that he had just resigned saying that he had accepted a position with the Bank of London & South America, also in Manaus. Without a moment's hesitation, I walked into Mr. Moon's office, he was the Manager, saying "Sir. I understand that Charles Reade has just resigned. I would like his position." Mr Moon looked at me for a moment, then he asked "How old are you?" " I'm 20 and a half" I replied. "Well wait until you are 21, then ask me again." On

the 28th February 1936, I went to the office of Mr. Charles Good, the General

Manager of Booth & Co (London),Ltd in Pará, who was doing his 6 month's

stint in the Liverpool office. "Sir. I am 21 today and I would like to go

to Brazil. May I go?" When not in Brazil, he lived with his wife and two

daughters in Meols and I knew them very well. "You still have 2 months left

of your contract. However, if you are so keen to go, I will arrange it with the

company. Meanwhile, it would be a good idea if you started to learn Portuguese." So that was that. The firm gave me £50 to buy myself suitable tropical clothes and a list of what they recommended. At least the list was concocted from ideas given by a Director who had spent 6 weeks in North Brazil in 1898 and a Mr Shipton who had spent 6 months in Manaos in l904. As a result, amongst items recommended were flannel pyjamas (the tropical nights are quite cold) 6 hats including one for wet weather, 24 white linen shirts with separate collars and 12 stiff white collars. Shoes a size larger than normally worn (feet swell in hot weather) and 50 yards of white linen to be made up in white suits in Brazil. The only time I had had anything to do with the Grand National was in l933 when, I believe, Golden Miller won. The firm received from their New York office, the winning ticket which belonged to one of their clerks. The money had been deposited in Midland Bank in the name of Alfred Booth & Co. Ltd and I was detailed to go to the bank and collect it. The money would then be transferred to the New York office where the lucky clerk would receive it. I went to the bank with a cheque for £30,000 and I remember that I was paid in 28 bank notes of £1000 each and four of £500. The one and only time I ever handled such large bank notes. When I was moved into the Cash Department, I wondered why it was necessary to have two cashiers. Few passengers actually came into the office to book their passages, shippers usually sent a boy round with a cheque to pick up the Bills of Lading and not many firms sent someone to receive payment for some invoice or other. Then I discovered that the second cashier's job was to pay the allotments to the seamen's wives and pay off the seamen at the end of voyages. The firm didn't want rough looking seamen in the office nor their wives for that matter, so they rented a room in the basement. Maggie Booth, the wife of the Chairman, used to be present when the seamen were signed on a vessel. She would badger the men until they agreed to provide a reasonable sum of money from their pay to be kept back for payment to their wives whilst they were at sea. Batchelor seamen were persuaded to have part of their pay kept back for when they returned from a trip thus preventing them from spending all their money on wine, women and song. When, each week, the wives would come to the office in the basement for their week's allotment, Maggie would ask how they were. If they or their children were sick, Maggie would see that food was sent to them and even medicines. All seamen received a copy of the Bible to take with them. My principal work in the Cash Department was to enter up the Cash Book and balance it at the end of the day. I was not allowed to go home until the books had been balanced. One day, fiddling around in the cash drawer, I came across two black Bradbury pound notes and some loose change. I asked the second cashier what it was there for. In a whisper, he said "Shorts and Overs". Then he explained that if they were unable to balance the Cash at the end of the day, they would use the 'shorts and overs' to complete the balance until the following day when they had more time to sort out the error. I collected Coins so asked if I might exchange one of the Bradbury notes for a current note. It was agreed. Later, I began to think that £1 was a lot of money to spend on a piece of paper which might get lost, burnt or otherwise destroyed. Taking the note to a shop I tried to buy something but the shopkeeper refused to accept it. Then I took it to the Bank of England in Fenwick Street. The cashier seemed to think I had stolen it! Anyway, he finally agreed to change it. The

weeks before sailing to Brazil, I spent going around England visiting all my aunts,

uncles, cousins and friends to say good-bye.

A pocket compass to find my way in the forest All those items were duly packed and I still have the pocket compass (never used).One of the last things I did was to call at the Liverpool Tropical School of Medicine for a medical check-up. After the doctor had examined me, he told ne that I was a very lucky young man "You will probably never be worried by the insects in South America as your blood has the wrong taste for them. Strange though it may seem, but I was never bitten whilst in Brazil or Peru save for the night in Cascavel in Brasil when I was bitten by a vampire bat. Doubtless the bat died a horrible death as a result. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|