Why Bolivia?.....

I'm not sure I can answer in a word and so not to let you glaze over I'll move

on to the story. The most I can say upfront is that Why Bolivia? is the

working title of a book I began in the mid-1990s and never completed. Why? I am

uncertain but thankfully I have the oral history on paper as two of the principal

characters are no longer with us....They were good story-tellers.

Bolivia

will forever be etched on my memory as I met Marion, my wife in La Paz the capital

back in 1963. Now comes the memory lane bit and it's short. I promise.

Bolivia

is a land about twice the size of France and back in the early 1960s it was just

about off the map. Roughly a third of the country is Andean with splendid snowcapped

mountains and the rest is lowland, often forested with huge rivers leading to

the Amazon or River Plate. Only one road was surfaced and that was  shattered

by countless potholes for the full 480 kms. Just three and a half million people

lived there and they were largely the ethnic Aymara or Quechua indigenous to the

central Andes. shattered

by countless potholes for the full 480 kms. Just three and a half million people

lived there and they were largely the ethnic Aymara or Quechua indigenous to the

central Andes.

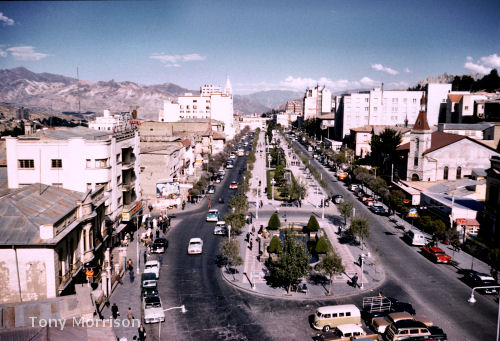

La Paz nestling high in the mountains numbered about 300,000 - not much more than

many large towns today. The photo on the right of the main streeet, El Prado,

was taken in 1961.

So

far so good? There are no more stats and I'll move on with two unforgettable characters

who very sadly have left the stage. Dr. Franz [Pancho] Ressel, a cancer specialist

and Alfredo La Placa [Freddie] one of South America's leading artists.

1961

La Paz

In 1961 I visited Bolivia with five other graduates from my University and we

were given a splendid welcoming party by the British Ambassador, Gilbert Holliday,

a slight, wiry and cheerful person. Oh yes - they put on a show in those days

as even getting to Bolivia was a challenge.

The

guests were varied with some from the UN Project we were to study and half a dozen

Britishers in grey suits surviving from the heyday when British-built trains were

running on the same British-built railways which had crossed the mountains since

Victorian times. In those days grey suits suggested the trains ran to time.

Other

guests were varied ....' 'Meet George' ....stocky and bespectacled. 'He imports

scotch whiskey..' and 'meet Archie'..... gaunt and receding hair ... 'He runs

a bank... the exchange part y'know'... 'And here's Dr.Ressel he is one of our

British Council funded scholars and just back from England. He speaks English

very well'.

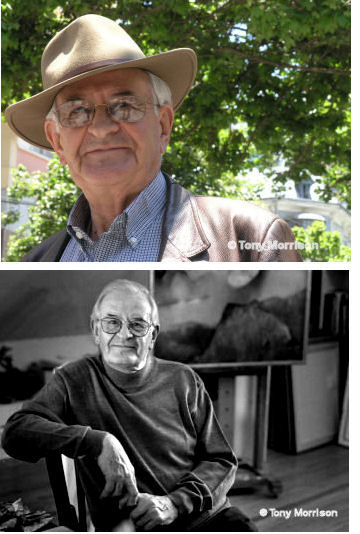

Franz

Ressel Franz

Ressel

Now

I must admit that while the UN Projects were 'all very fascinating' Dr. Ressel

better known as Franz or Pancho and who had a second generation German

background had actually travelled to some very remote parts of Bolivia.

Well... as you can imagine Franz had me spellbound from the first handshake and

fired my imagination with his clear, factual tales.

In

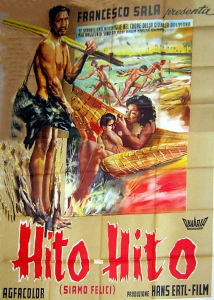

1957 Franz Ressel had been to the Amazonian forest with Hans Ertl, a German mountaineer

and film-maker, to make Hito Hito a big screen movie of the Sirionó

tribe for a Munich production company. In

1957 Franz Ressel had been to the Amazonian forest with Hans Ertl, a German mountaineer

and film-maker, to make Hito Hito a big screen movie of the Sirionó

tribe for a Munich production company.

In

post war Germany and in Bolivian cine circles Ertl was revered as he had worked

for Leni Reifenstahl. Among many Reifenstahl films he had been a senior cameraman

on Olympia the award winning but highly controversial film about the Berlin

1936 Olympic Games. Ertl

had taken shots from the ski jump holding a camera to his chest while in the air.

In the years post-war Ertl had filmed the German first ascent of Nanga Parbat

8,126 m in the Himalayas and in Bolivia had climbed many Andean peaks. But

all that's for later and so moving on, Franz was a doctor specialising in cancer

diagnosis and during his stay in London in 1958 had trained at the Royal Marsden

Hospital prompting from me such questions such as 'was cancer prevalent in the

Andean people and what native medicines, especially the plants did they use?'

Less than

two years later I was back in Bolivia and making films for a BBC TV series Adventure,

the brainchild of an energetic young producer David Attenborough. I was to make

seven films working under the Nonesuch Expeditions banner created with Mark Howell,

a close friend who was on the University expedition, and Franz Ressel was our

contact Numero Uno. From then on he remained one of my firmest friends through

dozens of journeys in Bolivia until he died in 2009.

The

learning curve began with the very first film of my 1963 schedule. We were after

a story about the Aymara people who live largely on the altiplano, a plateau at

an altitude of about 3.800 m. My working title was Children of the Lake,

referring to Lake Titicaca, one of the world's most unusual lakes and the focus

of Aymara creation myths. The

learning curve began with the very first film of my 1963 schedule. We were after

a story about the Aymara people who live largely on the altiplano, a plateau at

an altitude of about 3.800 m. My working title was Children of the Lake,

referring to Lake Titicaca, one of the world's most unusual lakes and the focus

of Aymara creation myths.

Franz

worked from a small laboratory in Calle Yanacocha one of the steep streets near

Plaza Murillo, the main square of La Paz. Laboratorios Securitas was on the first

floor. It was not smart but was highly efficient with an extraordinary NEOZET

microscope made by Reichert, Vienna, Austria as a centrepiece.

Eliana

- shortened as Eli Franz's wife who always wore a white technicians coat ran the

business side keeping check of the constant flow of samples [biopsies and more].

'White coats go with my work' said Franz. 'People expect them ... Just as they

expect explorers to have a week's growth of beard. You must grow one for your

film. Ertl always had a beard.'

The

laboratory became a regular meeting place and as Franz knew I had plenty of experience

of microscopy we often chatted about techniques as much as film-making. The sessions

were often staccato as the preparation of samples followed a strictly timed sequence

during which we would sip small cups of piping hot api, a semi-gloopy concoction

and favorite local beverage.

The api was made from finely ground purple maize mixed with cinnamon and

was provided by Pedro an elderly street vendor, a cholo [mestizo] well-known to

Franz. Pedro always climbed the stairs with great agility soon after I arrived.

I had the impression he had been watching the door and followed me inside to get

a quick sale.

In

1963 Lake Titicaca was overlooked by magnificent snowcaps and we planned to film

in villages along the lakeside for a couple of weeks. I say 'was overlooked' because

the snow now has receded thanks to climate change. But in 1963, while the images

would be visually exciting, the Aymara around the lake had already more than four

centuries of contact with Europeans. I needed to find a community where something

of their original way of life still existed.

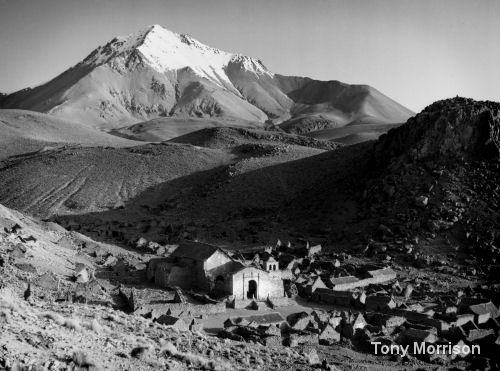

Santiago

de Collana

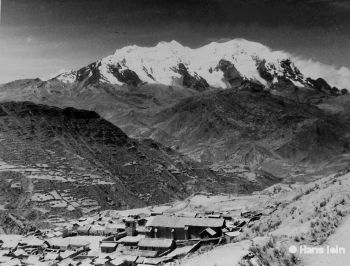

Franz

suggested we should try to visit Santiago de Collana a tiny village on the flank

of Mount Illimani [6,438 m] and he showed me a photo taken by Hans Lein, an artist

friend. They had been there together some years earlier Franz

suggested we should try to visit Santiago de Collana a tiny village on the flank

of Mount Illimani [6,438 m] and he showed me a photo taken by Hans Lein, an artist

friend. They had been there together some years earlier

The

prefix Santiago - meaning St. James the Great, brother of John the Apostle and

Patron Saint of Spain - hinted that some Spanish priests had been there in the

Colonial era. But then, where had they not been. I didn't realise it at the time

but the imposition of one religion on another in Andean history was being logged

in my grey cells for a great story in the future. The

choice suited me well as the name Collana was derived from the centuries old name

for the Aymara who were known as Collas and much respected as they had never been

subdued by the Inca coming in from Cusco in the north. Enter

Alfredo La Placa  It

was during one of our api sessions that Franz suggested we should add his

schoolfriend Freddie La Placa to the team. Better known today as Alfredo La Placa,

he had been at the German school in La Paz [Colegio Aleman 'Mariscal Braun']with

Franz. It

was during one of our api sessions that Franz suggested we should add his

schoolfriend Freddie La Placa to the team. Better known today as Alfredo La Placa,

he had been at the German school in La Paz [Colegio Aleman 'Mariscal Braun']with

Franz.

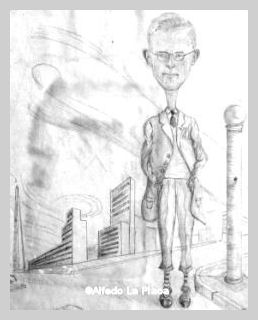

Many years

later I was shown a caricature of Franz drawn and signed by Freddie 'my friend

Ressel in the middle of La Paz'. In the background are the modern buildings of

a late 1930s La Paz. On

my first visit to La Paz in 1961 the architecture of the ne Avenida Camacho, the

Oblelisk and the older Avenida Mariscal Santa Cruz on the right were eyecatching.

Freddie

was born in Potosi a small but very historic city which in 1963 was about two

days away by bus. Potosi is now a World Heritage City filled with museums and

churches left from the heyday of its 16th Century silver production.

Freddie's

father Amadeo La Placa was of Sardinian origin and his mother from a Spanish Bolivian

family. Freddie whose olive almost Mediterranean complexion coupled with an instant

smile and love of beautiful creations immediately appealed to me. 'Here's a friend'

I thought - and so it was to be for over fifty years. And for me and Marion who

was now part of the team, Alfredo was always Freddie.

Santiago

de Collana is only 24 kms from Plaza Murillo but in 1963 it was not connected

by road. So how about hiking? The village lies on the side of a dry valley at

3790 m and the route follows a series of ridges eroded sometime at the end of

the last ice age at the foot of Mt Illimani. Camping was not an option as 50 years

ago the Aymara villagers were unwelcoming and staying on their land overnight

was ill advised. Franz who had been there said we must leave at dusk. Santiago

de Collana is only 24 kms from Plaza Murillo but in 1963 it was not connected

by road. So how about hiking? The village lies on the side of a dry valley at

3790 m and the route follows a series of ridges eroded sometime at the end of

the last ice age at the foot of Mt Illimani. Camping was not an option as 50 years

ago the Aymara villagers were unwelcoming and staying on their land overnight

was ill advised. Franz who had been there said we must leave at dusk.

From

the point of view of a film story Santiago de Collana was perfect. There we had

a 'closed village' as a focus point, a spectacular mountain backdrop, and a blend

of Spanish with Aymara religion. But even with a cut-down selection of filming

gear we would be carrying a 'load' so Franz offered a solution.

A

dirt road towards Mount Illimani led within five kilometres of the village and

we could arrange a Land Rover to drop us and to pick us up in the valley of the

River La Paz below Collana. 'There's a narrow mule path down the hillside' said

Franz but what he didn't say was it was a descent of about 950 m which to us was

just less than the height of Snowdon, the mountain in Wales. And we would be descending

in the dark. The

journey The

expedition was born. We borrowed a Land Rover from the British Embassy Technical

Assistance section ... ' OK if you pay for the fuel, the driver Moises and all

meals'. 'Cheap at the price - a snip'.. As I said 'they put on a show in those

days'. All went

to plan and the team? Allan Reditt my old schoolfriend was the Nonesuch business

manager - he carried the cash and 'fixed things'; Mark with his miniature Swiss-made

Ficord battery-run sound recorder; Franz and Freddie with rucksacks carrying food,

lights and spare cigarettes. Franz advised us to take plenty of cigarettes as

gifts. I carried one of our two Bolex 16mm cameras some lenses and film. Our kit

was good, solid, everyday clothing. In 1963 our kit was anthing but flash and

we still get a web credit from Grenfell cloth who provided our windproof jackets!

We

were dropped off on a stony hillside, barren apart from clumps of yellowing, ichú

mountain grass and a few small flowers. We began the walk. Freddy was fascinated

by the reddish mineralised colour of the stones and he stopped more than once

to examine and collect small pieces. As an artist he drew enormous inspiration

from the lines and cracks. We

were dropped off on a stony hillside, barren apart from clumps of yellowing, ichú

mountain grass and a few small flowers. We began the walk. Freddy was fascinated

by the reddish mineralised colour of the stones and he stopped more than once

to examine and collect small pieces. As an artist he drew enormous inspiration

from the lines and cracks.

Franz talked about the plants, many of which the Aymara used medicinally or for

ritual. One red globe shaped flower stood out. The leaves were spined and the

plant stood in clumps about 30 cms high. This was the 'Orquo itapallu'

the local name for Cajophora horrida [also as Caiophora] and an

infusion made with the flowers was used for colic and enteritis.

We were

within sight of the village when an Aymara man came along the path and Franz who

had been born in the mining town of Oruro south of La Paz town had a good knowledge

of the local languages and greeted him in Aymara. We were

within sight of the village when an Aymara man came along the path and Franz who

had been born in the mining town of Oruro south of La Paz town had a good knowledge

of the local languages and greeted him in Aymara. Then

came a quiet ritual. They sat and talked with Franz offering a cigarette and matches

and the man returning the hospitality with some coca leaves and a white chalky

lump. Franz took both and looked at the leaves carefully commenting on their quality.

Both smiled and the ice was broken. Our walk continued, now with a local guide.

Later

Franz told me that the custom was to offer villagers matches as they and cigarettes

were something 'special from outside'. The coca leaves were a sacred mild narcotic

from the coca plant Erythroxylum coca or 'mama coca' which had been

used for centuries by the Andean peoples and the white chalky lump was llicta

an alkali made from plant ash turned into a paste with urine and then dried. Later

Franz told me that the custom was to offer villagers matches as they and cigarettes

were something 'special from outside'. The coca leaves were a sacred mild narcotic

from the coca plant Erythroxylum coca or 'mama coca' which had been

used for centuries by the Andean peoples and the white chalky lump was llicta

an alkali made from plant ash turned into a paste with urine and then dried.

The

llicta when chewed with the coca releases the narcotic. I had noticed that

Franz had been chewing away very happily and getting a good response from our

guide.

Collana

turned out to be a great success. We filmed a small fiesta of masked dancers outside

one of the mud brick houses. They were mimicking the Spaniards who had invaded

their land. Collana

turned out to be a great success. We filmed a small fiesta of masked dancers outside

one of the mud brick houses. They were mimicking the Spaniards who had invaded

their land.

We

filmed some curious cross like markings made with bones in the stony central plaza

and we watched the time.

The

sun was dipping and the sky around Mt Illimani was turning a chill mauve, the

snows on the heights just 17 km away were catching the last of the sun and they

glowed perfectly. It was the moment to roll the credits and head for the mule

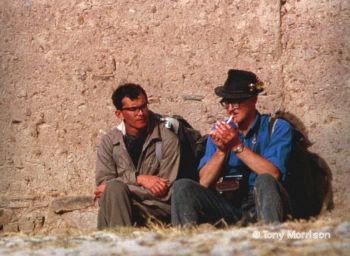

path. Here Franz

is with Mark and they are enjoying a cigarette against the warmth of an adobe

mud wall.

The

descent If

you have ever stood and looked over the edge of a high cliff.... well indeed ...

the path began at the edge and in the darkening view, the river in its latticed

shoal-filled bed could just be seen. Think. It was a single-file walk with a gravelly

surface and in many places nearly sheer for hundreds of metres. In those mountains

the change from dusk to black is sudden and we decided that I should move on with

Mark to get to the bottom and find Moises and confirm we were on schedule. Our

destination was Mecapaca a small village of mud brick houses and ichú

thatched roofs. If you should consider going there let me say it has changed.

In fifty plus years it has become a suburb of La Paz. Or in Real Estatespeke,

' The climate is good ... it is lower and warmer and it is away from the city

bustle'. Don't mention the main river and the shallow tributary I had to cross

which luckily was almost dry. In the wet season? Don't ask. Mecapaca is in a canyon.

We

reached Mecapaca in serious gloom as it had no street lights and followed a narrow

rutted and unmade street to the plaza where we found the Land Rover parked outside

the village store. Inside and lit by a kerosene light Moises was sitting drinking

coffee at a shabby floral patterned oilcloth topped table. We exchanged greetings

and waited. After an hour there was still no sign of the others. The full story

is in the book Journey Through a Forgotten Empire written by Mark

and published in 1964.

In précis - Franz had slipped on the downhill path and broken his ankle.

He had to be supported by Allan and and Freddie until they reached a place where

Moises and villagers could help them cross the tributary. We arrived back at Franz'

home very late and climbed the steps to his house carousing in a drunken unmelodic

charade with occasional curses to surprise Eli. Luckily the ankle healed and the

story continues. The

Confiteria - Club La Paz

But

for the next journey Franz was still on crutches and hors de combat. I

met Freddie in the Confiteria of the Club La Paz on the ground floor of

a 1930s Art Deco building, now a protected, historic piece of architecture. Possibly

the building was one of those in the background to Freddie's sketch of Franz. But

for the next journey Franz was still on crutches and hors de combat. I

met Freddie in the Confiteria of the Club La Paz on the ground floor of

a 1930s Art Deco building, now a protected, historic piece of architecture. Possibly

the building was one of those in the background to Freddie's sketch of Franz.

In 1963 the Confiteria was the accepted meeting spot for artists, journalists

and émigrés of many nationalities. Today it seems to have acquired

the reputation of the place where ageing Nazis kept quiet. Maybe it was......

but when I met Freddie the ex-Gestapo set was not obvious. The

coffee was excellent and came from some steep mountain valleys only a few kilometres

away. Freddie always chose a cortado or strong black with a touch of milk

to cut the acidity. I went for a con leche as I relished the un-treated

and rich local milk .

So

to planning. Our next film was a Search for a Lost Language set in Carangas

Province a wilderness of salt lagoons, salt marshes and a mat of saline grassland

at an altitude of about 3,700 m close to the Chile border. By now you will be

getting the idea that all our locations were somewhere in the clouds.

The 'lost language' was that spoken by the Chipaya a small group of highland people

then numbering less than 1500 who still spoke a dialect of Uru-Chipaya once widespread

across the altiplano south of Lake Titicaca. Freddie

arranged for me to meet Julia Elena Fortún, Bolivia's leading anthropologist

and folklorist who suggested the Chipaya had sought refuge in the wilderness in

the face of the dominant Aymara and the invading Inca. And from Julia Elena I

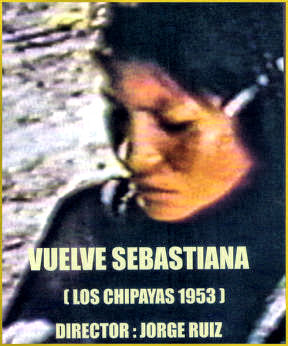

was put in touch with the Bolivian Cinematografic Institute and Jorge Ruiz . Bolivian

film-makers had a special interest in the Chipaya people, as Jorge Ruiz who was

one of Bolivia's leading directors had made  a

short ethno-drama with them in 1953. a

short ethno-drama with them in 1953. The

Institute was in Calle Ayacucho another steep street close to Franz' laboratoy

so I went along to the small screening room where I saw Vuelve Sebastiana Vuelve

Sebastiana Vuelve

Sebastiana [Come back Sebastiana -28 mins ] was a story about a young Chipaya

girl, who became involved with an Aymara and had left the village. By

1953 Ruiz was making films with ethnic actors and in the case of the Chipaya he

also involved a French anthropologist Jean Vellard who had spent time with the

group. The 1950s were a time of great political tension in Bolivia and Ruiz's

films showed much of the struggles over the land. We

viewed Vuelve Sebastiana which has since become a landmark in Latin

American film-making. But our production had no deeper pretensions than being

a way-of-life documentary set in the Carangas wilderness and Ruiz's film gave

us a good idea of what we would see. To help us on our way we were granted temporary

membership of the Instititute. Onwards

to Chipaya All

the preparations led us 225 kms south from La Paz to Oruro, a dusty, and in winter

a bitterly cold mining centre to where Freddie's parents had moved in the 1930s.

In

1961 the South American Handbook was the guide book for serious travellers.

'Oruro can be reached by express train from La Paz in eight hours. Hotel:

Repostero. There is little to interest the tourist'. By 1963 not much had changed

and we would travel by the dirt road from La Paz which with a couple of stops

could be done in about an hour less than the train. We stayed at the Repostero

- an unmissable experience.

My

other memories of Oruro in those days are hazy except we had to fill four jerry

cans with extra fuel and at Freddie's insistence stop at a tiny hole-in-the-wall

restaurant for a meal. Looking back I feel Freddie must have wondered what lay

ahead with a Land Rover stuffed with sleeping bags and dried food.

We

ate well in totally unpretentious discomfort. The ubiquitous floral oil cloths

covered the tables, the other diners wore thick dull brown overcoats and some

wore hats. It was cold. A vintage upright oil heater emitted a vague warmth and

a smell of kerosene - thinks? Maybe that's my lingering image with nostrils still

quivering. But the food was five star excellent. The roasted mutton came from

sheep grazed on the salty grass of the nearby plain - deliciously flavoured and

tender.  These

days, this local mutton, roasted, as a stew or fried is recommended as an expensive

delicacy in Oruro's restaurants but for us in 1963 it was a substantial meal and

our last for almost a month. The potatoes were local, yellowish and boiled and

the spicy sauce llaqway uchu a name from Oruro's Quechua ethnic heritage

simply tickled the palate. It was as memorable a meal as any traveller could wish

for. These

days, this local mutton, roasted, as a stew or fried is recommended as an expensive

delicacy in Oruro's restaurants but for us in 1963 it was a substantial meal and

our last for almost a month. The potatoes were local, yellowish and boiled and

the spicy sauce llaqway uchu a name from Oruro's Quechua ethnic heritage

simply tickled the palate. It was as memorable a meal as any traveller could wish

for.

Did we

have wine... I doubt it even though the street-side stalls displayed wicker covered

demijohns of Chilean Underagga both tinto and blanco. I kept to

the Huari Pilsen a German beer made about 100 kms further south at the edge of

the Azanaques hills and reckoned to be the best in Bolivia.

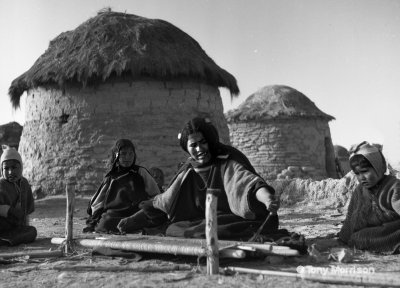

Our

next stop was Santa Ana de Chipaya the main village 160 kms away. We crossed two

rivers - survived one serious 'bogging' and several hours digging to get out and

then after about a day reached a village of thatched round houses built of salty

earthen sods.

We

filmed ancient burial towers or chullpas complete with corpses still half-wrapped

in hand woven cloth from a bygone era. Dark brown plaited hair covered some skulls. We

filmed ancient burial towers or chullpas complete with corpses still half-wrapped

in hand woven cloth from a bygone era. Dark brown plaited hair covered some skulls.

We filmed the

daily life as much as we could see, including hair plaiting, the women weaving

and made recordings of Chipaya music. The men were noted for their skill using

ancient bolasses for catching flamingoes in flight... and we were filming in colour

even though the TV transmission of the early 1960s was still in black and white.

Freddie with two Chipaya men

wearing their traditional tunics and domed felt hats  Freddie

helped us to understand the Spanish to Chipaya dialect but his days were spent

collecting rocks especially pieces of the ancient sun drenched 'desert pavement'

wherever it appeared. Freddie

helped us to understand the Spanish to Chipaya dialect but his days were spent

collecting rocks especially pieces of the ancient sun drenched 'desert pavement'

wherever it appeared.

His

best pickings came from the volcanic hills behind Escara an Aymara village 20

kms away to the north where being foreigners we had to check in with the Police

Post. The frontier with Chile and a line of great volcanoes was less than 100

kms away across a near trackless wilderness.

Later

in the year our filming led to parts of the Amazonic lowland but neither Freddie

nor Franz joined those adventures. Franz took a short contract working for The

Institute for the Study of Man in New York. Freddie was raising a family in La

Paz and was appointed Artistic Director of Artisanias Bolivianas [covering

arts and crafts] which brought him into the field of the myriad ethnic crafts

of Bolivia. Bolivia

again and again For

the next three years I continued to make television films in Bolivia and Peru

getting to know the basics of the languages and the history of the people until

in 1967 when married to Marion we set out to spend three years filming in the

Andes mountains.

Our

first story was for the prestigious Anglia Television's Survival

series with its truly global distribution. We set out to scour the wilderness

of southern Bolivia for the world's rarest flamingo and other elusive wildlife

for Land Above the Clouds a film in colour and a book. Our

first story was for the prestigious Anglia Television's Survival

series with its truly global distribution. We set out to scour the wilderness

of southern Bolivia for the world's rarest flamingo and other elusive wildlife

for Land Above the Clouds a film in colour and a book.

And

undaunted by our camping diet of corned beef, carrot and potato stew or the slightly

up-market ... very tasty when you are hungry ... Potato with Argentinian corned

beef and carrot stew,... Freddie joined us for one of the longest journeys. To

South Lípez  By

Land Rover we headed south for more than 700 kms to the now well-known Laguna

Colorada, a lake reddened by algae set among volcanic peaks, some dormant and

some steaming with activity. By

Land Rover we headed south for more than 700 kms to the now well-known Laguna

Colorada, a lake reddened by algae set among volcanic peaks, some dormant and

some steaming with activity.

On

the way we visited two 17th century silver mining towns. A small community of

Quechua people lived in San Cristóbal de Lípez but the people have

since been moved to make way for a mega mining project. San

Antonio and the New World And

then to San Antonio de Lipez a ghost town near the frontier with Argentina.The

old town lay at the foot of the snow capped Nuevo Mundo - New World - mountain

5,933 m. These days the mountain is often known as Cerro Lipez but on our old

maps it was Nuevo Mundo and a superb landmark.

San Antonio had been deserted for almost two centuries and on our visits, (Marion

and I had previously been there in 1963) we encountered just one man. He told

us he was there to take care of the church and his family lived by herding llamas

and alpaca on the plain at the foot of the mountain. Some

beautiful natural art .....and some priceless paintings  I

can recall Freddie's excitement as he found more volcanic rocks and some silver

ore slag. The photo on the left shows the striking colours in some of the ore. I

can recall Freddie's excitement as he found more volcanic rocks and some silver

ore slag. The photo on the left shows the striking colours in some of the ore.

The old church was filled with paintings and he was concerned that we should not

publicise their value as religious art was finding ready sale in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

A link at the

end of this page takes you to a story about San Antonio and a Spanish Colonial

painting of The Last Supper. The ancient church collapsed in the 1980s

and it's works of art were eventually transferred to Potosi. The

Fiesta of San Juan It

was on the journey back to La Paz when we experienced Bolivian history in the

making. We had passed many small settlements where small fires were blazing for

the Fiesta de San Juan (Saint John the Baptist) and children were leaping

over the flames as part of a pre-Spanish Catholic ritual to mark the June solstice

- there it was mid-winter. Late

at night we stopped and camped about a hundred metres from the road and watched

as dozens of army trucks passed in a line throwing up clouds of dust shadowing

their dimmed headlights. Later we heard that the President, René Barrientos

had sent in his special army unit,the Rangers, to quell miners striking at the

Catavi mine near Oruro, an event now etched on the Bolivian psyche as the Massacre

of San Juan. The number of deaths varies according to the source but it is clear

that no quarter was spared for young or old. Green

Medicine By

the end of the 1960s our filming and writing was being turned more to the huge

forests of the Amazon basin by then threatened with unremitting destruction. In

the 1970s we were back in La Paz many times to make more films and write more

books. During

that time with scientific help from Franz and with Freddie as a 'presenter' I

began a pilot project on the theme of Green Medicine to explore the ethnic

use of plants. Both friends were still working in the capital and on one occasion

following an accident, Franz came to the hospital to shave my beard. As he approached

me with a razor... one of those sharpened on a strop - I sensed a glint in his

eyes.

By the

late 1970s Franz, Eli and their two children had moved to Germany where he had

a good contract with Boerhinger-Mannheim a pharmaceutical company. We met once

in London when he was attending a conference. Freddie was in La Paz and by 1978

was the National Director of Bolivia's museums. Then in 1979 Freddie was in Paris

studying French and more art from which time his career as an artist took serious

shape with exhibitions all over Latin America. With the exhibitions came awards

and fame as one of South America's leading painters.

After

some years in Germany Franz retired to Santa Cruz de la Sierra the capital of

lowland Bolivia which luckily for me was the base for our Amazon film-work. Santa

Cruz had useful air, road and rail connections so I visited Franz and Eli once

or twice a year and learnt that Franz had an obscure heart problem which meant

he had to avoid returning to the altitude of La Paz.

But

his enforced lowland life gave me the chance to persuade him to fix a meeting

with Hans Ertl who by the 1990s was living a hermit-like life on some forested

land towards the Brazilian frontier. Ertl named his plot La Dolorida -

the grieving - possibly for his daughter Monica. His favorite daughter had met

a very sad end. But

his enforced lowland life gave me the chance to persuade him to fix a meeting

with Hans Ertl who by the 1990s was living a hermit-like life on some forested

land towards the Brazilian frontier. Ertl named his plot La Dolorida -

the grieving - possibly for his daughter Monica. His favorite daughter had met

a very sad end. But

Hans Ertl and La Dolorida is another story. Our meeting in the forest retreat

was a great success and I captured many shots on my ten year old Leica. 'Oh that's

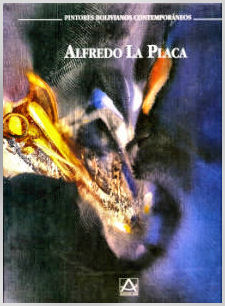

a beautiful Leica,' Ertl commented 'Let me show you mine. I used it at Stalingrad'. Freddie's

book  Back

in the mountains I called on Freddie in 2004 and we met in a small cafe in 20th

October street by then a favourite of artists and writers as the old town and

the Confiteria were no longer the centre of gravity. Back

in the mountains I called on Freddie in 2004 and we met in a small cafe in 20th

October street by then a favourite of artists and writers as the old town and

the Confiteria were no longer the centre of gravity.

Freddie

looking very fit and he presented me with his book titled Alfredo La Placa

from a series based on Bolivian Contemporary Painters.  In

the short biography he mentioned our travels together. Then in one of the introductory

essays Gerard Xuriguera writing from Paris commented on Freddie's work as it drew

themes from the earth, with its rich organic life and fascinating geology - '

La Placa' he said was a traveler with an erudite curiosity'. In

the short biography he mentioned our travels together. Then in one of the introductory

essays Gerard Xuriguera writing from Paris commented on Freddie's work as it drew

themes from the earth, with its rich organic life and fascinating geology - '

La Placa' he said was a traveler with an erudite curiosity'.

I

think we could endorse that idea with no trouble at all. Freddie was a marvellous

companion - he gladly suffered our expedition cooking and most evenings would

produce something he had found on the ground. Then in the ways of a student seminar

we would discuss and dissect - usually over some ice cold Huari Pilsener. In

2013 fifty years after Marion and I had met in La Paz we returned to Bolivia and

took Freddie and his wife Rita del Solar, a Bolivian celebrity hostess and fabulous

cook, with a few old friends to supper in a tiny Italian restaurant close to their

house...... I hesitate to think what Rita would have said about the potato and

carrot stew Freddie had to eat on our journey to Chipaya fifty years earlier.

Freddy was hobbling

from a broken ankle suffered on the steep street outside their home near the tiny

and very quiet Monticulo Park in Sopocachi, an old part of the city. Some time

later he and Rita moved from the steep street to an apartment on level ground.

In October 2016 he presented an exhibition in La Paz which he titled Red and

Black and dedicated it to saving the Earth. He died aged 87 on December 31st

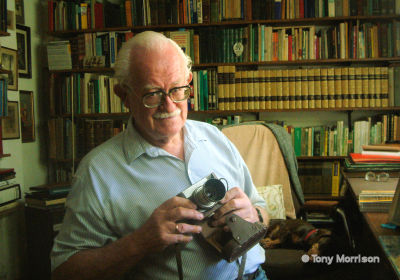

2016 and his legacy will forever be in his paintings.  Here

on the left Franz is with his classic Zeiss Werra 35mm still camera - made in

East Germany in the 1950s. It was one of the leading post war designs. Here

on the left Franz is with his classic Zeiss Werra 35mm still camera - made in

East Germany in the 1950s. It was one of the leading post war designs.

The

lens was a true Zeiss classic though mildly scratched from Franz's forest travels.

Only the lens cap was missing - maybe he lost it on the Collana adventure? After

I had taken this picture on a digital camera , Franz said 'Well this ancient film

camera will be a relic - maybe you would like it for your collection? It has pride

of place in my study.  Franz

died from cancer in 2009 in Santa Cruz and we learnt that he had spent his last

years tidying his research and writing a small book - as he said 'rewriting history'.

He always said 'Everything must be questioned and no stone unturned to find the

truth'. Franz

died from cancer in 2009 in Santa Cruz and we learnt that he had spent his last

years tidying his research and writing a small book - as he said 'rewriting history'.

He always said 'Everything must be questioned and no stone unturned to find the

truth'.

Franz

had published Enigmas in 2008 and signed a copy for me. Before his death

he put aside a pile of his collection marked 'for Tony' - some books, papers,

photographs,and memorabilia.

Perhaps the greatest treasures were his 1950s pictures and memorabilia from the

Beni part of Bolivia when he made his journey with Hans Ertl to the Sirionó.

All

life is beautiful When

we called on Eli in 2013 she told me how Franz had accepted his cancer. It seems

he had obtained a sample of his cells and seen them under one of the best microscopes

in Santa Cruz. 'Beautiful' he murmured as he was entranced 'All life... even my

cancer is beautiful'. Franz was 80.

Postscript

from Tony and Marion

I feel we can look back with wonder to many fascinating adventures, hours of compelling

talk and inspiration with these very close friends. So that is one answer to Why

Bolivia? And now looking forward?

There

will be more chapters and plenty of pictures. SEE

The

Last Supper of San Antonio, The

Princess of the Glorieta, TO

COME A Chipaya gallery, [pictures]. Hans Ertl and the Siriono, Lizzie and the

Lost Empire of Nicholas Suaréz,

Some data for Santiago de Collana

Height

3790m and 17kms from Mount Illimani

Coordinates 16 40 10 S 67 57 54 W

Descent

of 946m [3102 ft] to Mecapaca 2844 m

Mark

Howell - Journey through a Forgotten Empire published 1964 Background

for Vuelve Sebastiana - Testigo de La Realidad the work

of Jorge Ruiz by

José Antonio Valdivia , Bolivia 1998 Background

for the Sirionó- Nomads

of the Long Bow by Allan R Holmberg, Smithsonian Institution ,

Washington,1950 Lost

film - Our colour

film of Chipaya was lost in a processing laboratory in the 1970s and Hans Ertl's

film negatives were lost when the trailer to his tractor toppled into a river

in his forest retreat. That was, also sometime in the 1970s The

Werra

camera given to me by Franz Ressel in 2004 For

two totally different reasons this camera is a treasure.  The

first is its connection with Franz and his journeys in Bolivia. - More on that

by starting at the top pf the page The

first is its connection with Franz and his journeys in Bolivia. - More on that

by starting at the top pf the page

1957

In

1957 Franz accompanied Hans Ertl, his daughter Monica and Walburga Mõeller

on a filming expedition to the upper reaches of Cocharcas river, an Amazon tributary

in Bolivia. See picture right. The

expedition was to make Hito Hito the first film record of the Sirionó

- a forest tribe. Franz

took many colour pictures on this Werra using the German made Agfa reversal film

but after 60 years with many of those in the tropical climate, the colour has

'shifted' more to red. We have digitally restored some of the best. Here you can

see Monica Ertl and her father Hans in their German built Klepper boats - light

and collapsible canoes supplied specially for the Hito Hito expedition In

1958 Franz provided the English and Spanish translation for Ertl's book Arriba

Abajo, published in Germany and still available 'used' The film Hito Hito

is harder to find

Then came the Collana visit described at the beginning of this page and doubtless

Franz made many other journeys while he was working in highland Bolivia. We know

he took many photographs of medicinal plants as he gave us his collection You

could say this Werra has 'been around' The

Second Reason  Now

to the second reason why the camera is a treasure. Now

to the second reason why the camera is a treasure.

Werra cameras were made by Carl Zeiss in Jena, East Germany - remember in post-war

Europe Germany was divided into East - controlled by Russia and West by the western

powers. The name

Werra comes from a small river in the Wesler river basin of central Germany. Zeiss

lenses are outstanding with a pedigree dating back to 1846 and in post-war years

Russia took moved much of Carl Zeiss,Jena production to Kiev in the Ukraine. But

I believe this Werra was made in Jena by German engineers and its design as you

can see was sheer uncluttered simplicity. This

Werra 1 has the classic Zeiss 50mm Tessar lens with an f 2.8 aperture. A brilliant

- amazingly so, piece of optical engineering. The

shutter controlling the passage of light through the lens to the film is an East

German Vebur and is 'cocked' - or prepared for action by half rotating that large

leather covered cyclinder from which the lens protrudes. The metal protuberence

on the camera body left side in the picture is the connector for a flash cable The

satin chrome top of Franz' Werra is slightly scuffed above the lens where his

hand rubbed when winding the leather covered cylinder. . But the whole design

including the satin chrome the lens cover and lens cap could have come straight

from a Bauhaus drawing board of Germany in the the early 1920s. The lens cover

is reversable and doubles as a lens hood /shade  Bauhaus Bauhaus

Bauhaus

designs were notable for clean very functional lines without any 'frills' and

in this sense the Werra is unique. Most cameras of the era and even now have knobs

or dials - the more the merrier and 'must haves' for some enthusiasts Franz'

Werra is the Werra I the first of the series dating from about 1956. As

the 1950s moved on into the early 1960s other models were introduced.The market

dictated 'extras' such as built in light measuring a rangefinder or lenses which

could be changed to allow for telephoto or wide angle pictures. The last of the

series was the Werramatic E of 1966. If

you are looking for the extra lenses they are expensive [2016] but I'm more than

happy with this wonderful memento of a very great Bolivian friend - and the camera's

remarkable life.

|