Tony

Morrison writes in 2014…  If

the references had not been so good I would have thought I was being sent on a

wild goose chase. Piotr Zubrzycki a Polish geologist working for the Bolivian

National Mining Corporation was telling me an amazing story 'There's an old

mining town down there and it's full of history - San Antonio is a ghost town

and empty because it's so cold'. Piotr had graduated from Edinburgh University

and settled in La Paz with his family. If

the references had not been so good I would have thought I was being sent on a

wild goose chase. Piotr Zubrzycki a Polish geologist working for the Bolivian

National Mining Corporation was telling me an amazing story 'There's an old

mining town down there and it's full of history - San Antonio is a ghost town

and empty because it's so cold'. Piotr had graduated from Edinburgh University

and settled in La Paz with his family.

It

was 1963 and I was in Bolivia looking for themes for television films. Back in

London the BBC editors had given me plenty of freedom but I could hear their thoughts....'a

400 year old, tumbledown ghost town? Almost 600kms away and totally isolated in

an arid wilderness at an altitude of about 4,600m?' The

production cash-till was ringing. How could I even suggest it? Piotr said there

was a rough road for the first 250kms and after that, just tracks. 'With a

Land Rover you'll take four or five days to get there… and you will find

a near perfect Spanish Colonial church, gilded inside with a painted roof - also

....there are many old religious paintings.' San

Antonio de Lipez  I

had met Marion a few months earlier and we had become engaged - not really such

a spur of the moment decision I can assure you. We just wanted the same kind of

life so we said OK let's go for it and with three companions set out for San Antonio

de Lipes. I

had met Marion a few months earlier and we had become engaged - not really such

a spur of the moment decision I can assure you. We just wanted the same kind of

life so we said OK let's go for it and with three companions set out for San Antonio

de Lipes.

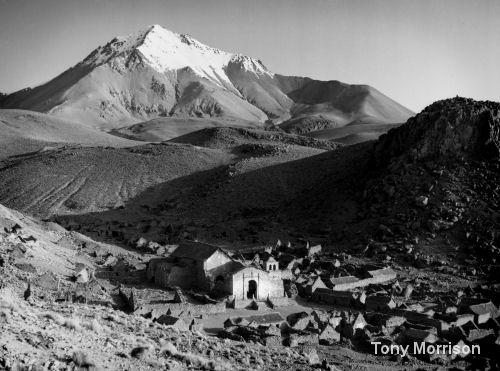

I'll mention here that the spelling is sometimes with a 'z' though old documents

use the Spanish form 'Lipes'. True to Piotr's estimate the old town came in sight

late on the fifth day. The track led over a shoulder to a view of a snowcapped

mountain El Nuevo Mundo - The New World and San Antonio was nestled in

a fold. The

ruined town is about 43kms away from the border of Argentina though when it was

built in the seventeenth century such national boundaries did not exist. This

area was part of Alto Peru of the Spanish Vice-Royalty of Peru seated in Lima

on the Pacific coast. In

1776 the control of the region was passed to the Audiencia de Charcas under the

Spanish Vice-Royalty of the Rio de La Plata seated in Buenos Aires. The

politics of the changes are for historians to discuss but in its heyday the wealth

from the mines of this region went by mules trains to the Pacific coast. And that

is for another story.... The

New World nountain is sometimes known as El Cerro Lipes but most genearlly

as the El Nuevo Mundo - with a height of 5898m and GPS of 21 54 53 S -

66 53 04 W. For our journey we did not have GPS and worked by an old Bolivian

map and for the last stage by local information. We were on the southern eastern

edge of the Salar or 'salt-pan' of Uyuni about 160kms away from the mountain and

a local pointed to a snowcap just topping the horizon and said 'that's El Nuevo

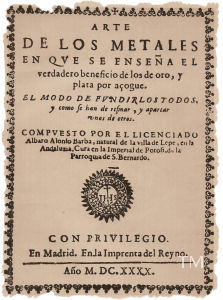

Mundo'. Padre

Alonso Barba and his Arte de los Metales published in Madrid 1640  And

true to Piotr's description the old town lay in ruins. The seventeeth century

miners were long gone. Piotr had found the place because in his search for viable

mineral resources in Bolivia he used the records of early Spanish miners and priests

such as the book written by Padre Alonso Barba in 1640 who knew the region well

- the provinces of Lipes were bywords for silver and hence wealth in the days

when Potosi, the famed Silver City, was a rising star in the Andes. Charles V

of Spain bestowed on Potosi the unforgettable motto 'I am rich Potosi, Treasure

of the world and the envy of Kings'. And

true to Piotr's description the old town lay in ruins. The seventeeth century

miners were long gone. Piotr had found the place because in his search for viable

mineral resources in Bolivia he used the records of early Spanish miners and priests

such as the book written by Padre Alonso Barba in 1640 who knew the region well

- the provinces of Lipes were bywords for silver and hence wealth in the days

when Potosi, the famed Silver City, was a rising star in the Andes. Charles V

of Spain bestowed on Potosi the unforgettable motto 'I am rich Potosi, Treasure

of the world and the envy of Kings'.

Alvaro

Alonso Barba was born 1569 in Spain, probably in the village of Lepe, near Huelva

in Andalucia and chose the Church for his life's work. Padre Barba journeyed to

Peru and his first curacy was in the village of Tiahuanacu - also known today

as Tiwanaku near Lake Titicaca. From there he was sent to the distant, and by

then flourishing provinces around Potosi. He stayed some years in to San Cristóbal

de Lipes, a small village but an important mining centre a few kilometers south

of the Salar of Uyuni. And from there he went to the Parish of San Bernardo in

Potosi. It

was in San Cristóbal that Padre Barba began his writing and experiments

concerning the mining and processes for the extraction of silver from minerals.

Padre Barba spent almost 50 years of his life studying silver production. No wonder

that Piotr relied so heavily on the priest - he knew so much. Our

copy of the book has a facsimile cover and was published in Potosi in 1967. The

wilderness of the southern Bolivian Andes, the old mines shown to us by Piotr

Zubrzycki and the story of Padre Barba riveted me for several years afterwards

and still does….. but all that is for later. This is about a painting of

the biblical Last Supper we saw in the old town of San Antonio de Lipes all those

years ago. We

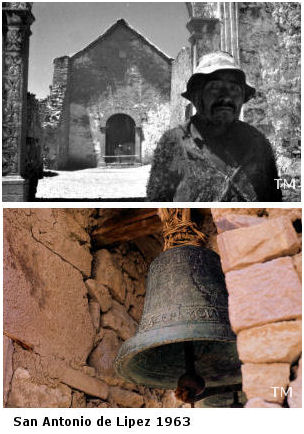

arrived in San Antonio   The

old town was not totally empty as one elderly man and his family lived there to

care for the church. Apparently a priest called by every year for a small festival

when a handful of llama herders gathered. The

old town was not totally empty as one elderly man and his family lived there to

care for the church. Apparently a priest called by every year for a small festival

when a handful of llama herders gathered.

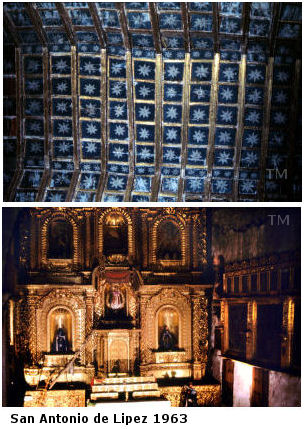

The

man opened the door using a massive key and showed us around.

And just as Piotr said it was heavily gilded. The wooden ceiling was gilded and

painted in dark blue with stars, and paintings of varying sizes by Spanish colonial

artists were hanging dust-covered on the walls.

It would have been a conservator's worst nightmare had it not been for the very

low humidity and the cold - it must have been sub-zero for much of the year. Two

huge brass bells with inscriptions and dates were hanging by bunches of leather

straps from bars in the stone-built tower. The

ancient building and the contents were a frozen time-capsule. My film camera rolled

and we had a fascinating end to a story. Our

old photographs I

took some photos - But remember. In 1963 my colour film for interiors was Kodak

Ektachrome transparency film and my electronic flash was simple and small. My

modern standards it was primitive ....but it was small as weight for travelling

was all important in those early days. The

35mm film pictures were on Nikon F cameras and they came off reasonably well considering

the conditions, but my larger size on Ektachrome of 6 x 6cms and taken on a Twin

Lens Reflex were not so good as the flash synchronising was slightly 'off'. At

the time I assumed the results were useless and the cut transparencies ended up

in a brown envelope labelled 'Old Spanish mining Lipez' at the bottom a drawer

labeled 'Bolivia'. And there they stayed for 50 years. But

technology has moved on and those old dark, almost black images have been tweeked

into life. Marion scanned them thinking seriously that they should be in one of

our 'special Collections' and abracadaba one of the negatives revealed

a painting of the biblical Last Supper. And the colour is fair considering the

age of the painting - perhaps 300 years, plus the 51 years of the film - Ektachrome

transparencies have a tendency to fade or change colour often to reds or purple.

The detail on the larger film is amazingly sharp giving some extraordinary detail. The

Last Supper in San Antonio de Lipes The

biblical Last Supper refers to the final meal of Christ before His Apostles on

the night before the Crucifixion. The gathering and meal are given different scholarly

intepretations but in the Andes of the seventeeth century the religion was Catholic

overlaying a rich indigenous reverence of the world of the mountain spirits, the

sky and the earth. Academically it is 'syncretism'. In

Catholic terms the painting appears to depict the institution of the Eucharest

with all the Apostles and Christ seated at the moment of the consecration of the

bread and the wine. If

the Unknown Artist was from a part-indigenous family or even purely indigenous

the symbolism is a valuable record of life at the time. The Apostles may have

been painted by copying but most likely they bear some resemblance in facial style

to the wealthy Spaniards or their family descendants in Potosi. And

the table settings and food are a special clue suggesting an indigenous painter,

most likely schooled under the Potosi master Melchor Peréz Holguin 1660-1732.

Holguin was born in Cochabamba in the eastern Andean valleys of parents from Potosi.

The years 1680 -1750 was a Golden Age for the Potosi painters and San Antonio,

needing paintings was in its prime.

The

San Antonio supper seen above and on the left is frugal and very typical of the

chill Bolivian Andes. On the silver plate the meat is from a small animal probably

the local cui, the guinea pig [Cavia. sp] The

San Antonio supper seen above and on the left is frugal and very typical of the

chill Bolivian Andes. On the silver plate the meat is from a small animal probably

the local cui, the guinea pig [Cavia. sp]

There

is substantial bread, some country style cheese much as made today and perhaps

a glass of chicha. The glass beside the right hand of Christ [above] is

filled with a cloudy liquid resembling the traditional fermented maize flour drink

of the Andes. But

most noticeable are the ajis or peppers, red and green, in each place setting.

Even in 1960s and 70s when we were in those cold places a traditional meal in

the Bolivian highland villages always included an aji or other local chile.

The aji was also very symbolic and used in preparing special food for offerings.

There

is a red aji close to the bread in the picture on the left.. The

Last Supper in Cuzco, Peru  We

have another 'Last Supper' photograph in our Andean collections - the now famous

painting by Marcos Zapata a Spanish-taught Quechua artist. The painting is in

the cathedral in Cusco completed in 1654 and built on one of the greatest Inca

shrines. Today

Cusco is the much visited Inca centre of Peru. We

have another 'Last Supper' photograph in our Andean collections - the now famous

painting by Marcos Zapata a Spanish-taught Quechua artist. The painting is in

the cathedral in Cusco completed in 1654 and built on one of the greatest Inca

shrines. Today

Cusco is the much visited Inca centre of Peru.

The

mind grabbing point of the Zapata painting is the food on the table - it is roast

guinea pig or cui, a native animal (Cavea sp) of the Andes. In

the painting we saw in San Antonio 1963 the dish looks very similar. But apart

from the cui, the silver plates and a lacy tablecloth with a decorated

edge, the rest of the setting has some fascinating differences. Picture

on Kodachrome 35mm film using a timed exposure.

The colours in Kodachrome are far more stable that those in Ektachrome  In

the Zapata picture the food includes simple bread and cheese. These are accompanied

by bananas, grapes and what appears to be maracuya or passion fruit. Cusco

is close to the warm sub-tropical valleys of La Convención province below

Machu Picchu. In

the Zapata picture the food includes simple bread and cheese. These are accompanied

by bananas, grapes and what appears to be maracuya or passion fruit. Cusco

is close to the warm sub-tropical valleys of La Convención province below

Machu Picchu.

Also, in the Zapata painting they appear to be drinking wine - the flask or decanter

is narrow-necked and the glasses are filled with a clear liquid. An hacienda

near Cusco was the earliest of Peru's wine producers. The

collapse of San Antonio church The

last time I was in San Antonio was in 1971. The church and its collection had

not changed. It was a time-capsule and still off the beaten track as mass tourism

had not arrived. Then in the 1990s, a traveller who walked much of the last 100

kms because the track had deteriorated and was covered with volcanic sand, reported

that the church's ichu grass roof had collapsed - the golden reredos had

gone and the ruins were empty. The family guardians had moved on. The collapse

was inevitable given San Antonio's isolation, and sad neglect. Potosi

- a chapel in the Santa Teresa Convent  The

artefacts had been taken to Potosi to be kept in a special chapel of the Santa

Teresa convent, founded in 1616 by the wealthy 'doña Ana Orquendo and her

husband don Lorenzo Nariondo de Orquendo at a cost of 1,00,000 pesos'. Money flowed

like water in seventeenth century Potosi. The

artefacts had been taken to Potosi to be kept in a special chapel of the Santa

Teresa convent, founded in 1616 by the wealthy 'doña Ana Orquendo and her

husband don Lorenzo Nariondo de Orquendo at a cost of 1,00,000 pesos'. Money flowed

like water in seventeenth century Potosi.

I

made a special visit in 1998 and sure enough the reredos was there with some paintings

but no sign of the Last Supper. All I could hope was that Bolivian conservators

and not international art traders were hard at work on that painting, and others

from the old church. Photo

on Agfachrome 35mm film My

film-making partner was Mark Howell and we had formed Nonesuch Expeditions almost

a year earlier. Mark wrote an account of the mini expedition in Journey Through

a Forgotten Empire published 1964. With

special thanks to the Instituto Cinematagráfico Boliviano, Julia Elena

Fortún, Ministerio de Educación, La Paz and Alfredo La Placa. And

to our companions Allan Reditt and Jackie Chester who were with us in 1963, cramped

together in the back of the Land Rover, and who are still shaking off the dust. Peter

Francis One evening in 1965 I gave a talk to the Imperial College Exploration

Board - London, and it fired the imagination of a group of geology students who

made a journey to San Antonio in the following year. One of the team was Peter

Francis who went on to an academic research career, eventually becoming Professor

of Volcanology at the Open University. The full report is on-line

- The Minas de Lipez [Bolivia] Expedition 1966.

I must mention here that the students recorded - ...One

of the biggest of these mining towns, San Antonio de Lipez has remained almost

exactly as it was when the Spanish left; the cathedral is still unbelieveably

intact, and a profusion of elaborate carving, gilding, and silver work around

the altar-screen testify to the former wealth of the area..... https://workspace.imperial.ac.uk/expeditions/Public/MinasDeLipezBolivia1966.pdf Peter

and his team sent a report to The Times, London with the dateline From a Special

Correspondent - San Antonio de Lipez , Bolivia and the story was published

on September 9th 1966.

SEEKING THE SECRETS OF SPANISH SILVER. Peter

Francis died in 1999

|