University

of Bristol Trans-Continental Expedition 1960 — 61 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

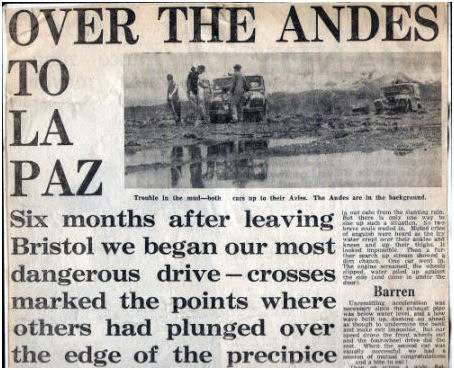

Crosses marked the points where others had plunged over the edge of the precipice. By our milometers, the road between the capitals of Peru and Bolivia - Lima and La Paz - is 983 miles long. It is nominally a usable road; that being the case we are wondering what the "uncompleted" sections are going to be like. We drove along this road. It took us seven days, or 81 driving hours, counting the various stops for rescuing the cars from mud, fording rivers and producing documents for policemen. We left Lima driving south on the Pan-American Highway, along the cliffs often high above the sea. This is a good road except for the quite frequent landslides; there were many points where bulldozers were clearing away rocks and sand. The many beautiful and quiet beaches with rollers are reminiscent of the Australian coast; and these waters are among the world's best fishing grounds, there are thousands of fish, and naturally, sea birds wheeling above the water and diving for food - frequently a couple of dozen splashes at the same time, as though a handful of gravel had been thrown into the water. Atacama desert Almost immediately on leaving Lima we were in the Atacama Desert, our first genuine sand desert. Sand encroaches on the road and there are lines of dunes beautifully sculptured by the wind. No shadows It was very interesting to see how a sandy desert meets the sea. Well, it does just that; it carries on, up and down and along and into the water. First desert, then dunes, then sandy cliff, then wide beach, then sea. This is a tropical desert and the sun stands very high. For much of the day there are no shadows, and very few desert plants exist to break the appalling monotony. In this burning waste there are many piles of bones, their startling whiteness making them awfully visible; they are almost all animal, of course, but we did see one human skull. Another unpleasant reminder of the dangers was the large number of wooden crosses marking the point where some unfortunate driver had plunged over the edge onto the rocks below. This was a three-day run of 600 miles, driving in the overbearing heat of the day and camping out in the exceeding cold of the night. Now we left the Highway and began the difficult climb up into the Andes themselves. We had seen them, snow-topped and cloud covered, away to our left; now we would climb them, even at times driving through the clouds. Deceptive That day it was exactly six months since we left Bristol and we celebrated it by beginning our most dangerous drive. At first the road was in straight stretches one or two miles long, and of most deceptive inclination; then a severe corner and another stretch. One corner had a little graveyard of 26 crosses - a bus had plunged over a year before. Then we dropped down into Arequipa (7,000 ft.) where there was a control point for passports, car carnets and everything else. We were surrounded by Quechua Indians wishing to sell things - or beg them. Arequipa is an old city that had suffered somewhat during the terrible earthquakes which devastated parts of Chile last year. It is dominated by El Misti, a superb mountain over 20,000ft. high, whose white peak was cut off from the lower foothills by a deep bank of cloud, giving it an unearthly effect of floating like a mountain in a Japanese painting. Here the real climb began, and all pretence at good road surface stopped. Also it began to rain. At first we crossed two valleys where there was some useful vegetation and many Indian farms. Then, as it grew dark, we started to climb in earnest. The road surface was loose gravel with innumerable hair-pins and with drops of hundreds of feet on the side. It was impossible to get out of second gear, the cars ploughed gamely on, the lights frequently swinging wildly out into the darkness before finding the road again. Arduous Tremendous concentration was necessary from the drivers. Often on a corner one would have to jockey to find the best route across a gully left by the rains. All eyes were watching the road (it was inadvisable to look over the edge). It stretched grey-black, with darker patches that warn of particular wetness, there were reddish stones on its surface, and larger, rougher, red rocks often formed the banks. In between these rocks grew many smallish plants and bushes giving the effect of a rock garden, and often down each side of the road would be lines of three-foot evergreens, that looked artificial - like a laid-out park, their leaves catching and reflecting the light. Then the rain stopped and the mountain El Misti appeared in the moonlight. It seemed that we were at the height of the snow-line, but probably were several hundreds of feet below it. It was now 8.30 and we found an ideal camping place just off the road. At around 10,500ft, the cold was considerable - sheepskin jackets were worn for the first time. We pitched our bivouac tents (also for the first time), had a hurried meal of mushroom soup and sardine sandwiches, crawling into our special double sleeping bags and went to sleep. It rained heavily in the night, but the tents proved more than adequate. So dawned Thursday, second of March, with the sun shining golden on the beautiful peak of El Misti. We were now 152 miles from Puno, our next scheduled stop, and if that seems a reasonable journey I can say here and now that it took us 20 ½ hours driving to reach it! We do not often indulge in such arduous feats, but as will be seen, circumstances demanded it on this occasion. Now, by daylight, we could see last night's unreal moonlit landscape. The road continued its determined climb - it took us 35 minutes to get out of bottom gear. Fast pulse There is no grass, just little bushes, rocks and earth. Yesterday's laurels retain the same impression by daylight and there are many smaller bushes - heather, broom, and later, small wild lupins. The rocks are covered with the most beautiful mosses, seeming iridescent in the sunlight, the colour range is extraordinary - dark reds and browns, bright tans and emerald green, and lighter patches of green lichen. Way down below we can see seven or eight stretches of our road; they are hidden by mounds and rises, then break out again - down and down, until lost in the lower clouds. From this height the delicate colours are lost, swamped in the general desolation, there are no trees to give interest and the dominate colour is the grey of the rocks and a sad green. We were now at our greatest height, over 16,000ft. The altitude was having some effect: we were all breathing deeper and pulse rates were faster. Marching along parallel to us was a fine range of eight or nine peaks, looking like a row of teeth, their snow-capped peaks gleaming in the sun and contrasting with the dark grey clouds immediately above, and the sombre shadows of the foothills. The road began to drop. It had deteriorated badly, heavy trucks had churned up the surface leaving deep ridges, deceptively swamped with water, and often too deep to be cleared by heavily loaded vehicles. On one occasion, whilst making a detour around such an impassable stretch, we had the extreme bad fortune to get both the cars bogged down at the same time. A line from the winch to a buried crowbar proved useless due to the softness of the ground; so there was nothing for it - one car had to be dug out in order to winch out the other. Digging at that altitude was a distinctly unpleasant exercise and the weather did not help. At one moment we were stripped to the waist in the hot sun, and the next were muffled against driving rain - we even had hail. Eventually the first car was free and had no difficulty in winching out the second. But the incident had taken two hours. Tired, but triumphant, we drove slowly on, only to be faced with a greater hazard. A river (that should have been a stream), 36 feet wide, obviously very deep and churning along all too swiftly. And no bridge.

Barren Unremitting acceleration was necessary since the exhaust pipe was below water level, and a bow wave built up, dashing on ahead as though to undermine the bank and make exit impossible. But our speed drove the front wheels out and the four-wheel drive did the rest. When the second car was equally successful we had a session of mutual congratulations … and a bite to eat! Then on across a wide, flat, rolling plateau, with a total absence of vegetation. High altitude desert, pronounced Peter, out of his geographical knowledge. Nobody disagreed; on the rare occasions when Peter stops quibbling about semi-deserts and fringe conditions, things are barren indeed. At the sides of the road were occasional patches of snow and we thought this might well be a snow-field at night. And night was coming fast and with it came the snow. So, nicely placed within the tropics, in theoretical summertime, with every expectation of sunshine, we battled along through this arctic weather, with the windscreens misting up inside and snowing up outside! Naturally the road did not improve; and there was so much it it, away further than we could see it stretched, a dirty sand colour with pot-holes and ruts and nothing to look at on either side. Round about this point we saw a sign which stated proudly: Alto de Toroyo, Altura 4,893 metres" Nearly 16,000 feet, and a small blizzard blowing! Ravine And it was getting very dark. Even though the snow eventually stopped, it was impossible to camp, nothing could be seen but water, wet wiry grass and mud. At about 7.p.m., having been on the move since 6 a.m, we had to decide to do the whole trip. We were all rather tired, but morale - as they say in the communiqués - was commendably high; and breathing the cold, thin air deep down into our sea level sized lungs, we carried on. This was the most dangerous part of the journey. We now had to descend mountain passes in three inches of soft, slushy mud. The slightest error in steering meant an immediate skid… with a ravine waiting at the side. The number of small white crosses increased alarmingly. Neither car crew wished for the melancholy task of adding three more. The

road ran away to the next hair-pin, the mud glistening in the headlights, only

interrupted by the almost incessant black pools of dirty water. These varied in

depth from one to six inches and it was nearly impossible to gauge them. So you

drove on slowly and steadily watching the water spray forward from the front wheels

into the light, and becoming inured to the jolting, jarring and sliding of the

vehicle. One and a half hours later we paused at the top of a hill, and there was Puno. Miraculously also, there was an open hotel. We extracted the bare minimum of requirements, tiptoed upstairs in the dark (no electricity at that early hour apparently, found our rooms, found our beds and dropped into them, asleep before we hit the pillows. To the city During the next two days we drove around beautiful Lake Titicaca, over 100 miles long and the highest navigable water in the world, across its fertile plain, through the Customs (45 minutes for both, a record), and at last into Bolivia. So, at 3.30 p.m. on Saturday - having left Lima the Sunday before at 12 noon - we were looking down on La Paz from the level of its airport (over 1,000ft above the town). The capital of 400,000 people, similar in size to Bristol, lies deep down in a complete basin, its altitude is 11,000 feet and around it are many peaks close to 20,000 feet. From the road above, it is the most amazing sight. Different coloured buildings can be picked out individually; it looks as though somebody had thrown down a handful of confetti. Impatient as we were, we stopped for 10 minutes, absorbed by this extraordinary view. But two things were calling us strongly - the prospect of mail, and the need to find accommodation. So we drove down into the city to look for both. | ||||||||

|

Six

months after leaving Bristol we began our most dangerous drive

Six

months after leaving Bristol we began our most dangerous drive  We

surveyed it gloomily, safe in our cabs from the slanting rain. But there is only

one way to size up such a situation. So two brave souls waded in. Muted cries

of anguish were heard as the icy water crept over their ankles and knees and up

their thighs. It looked impossible. Then a further search upstream showed a dim

chance. One car went in. The engine screamed, the wheels slipped, water piled

up against the side (and came in under the door).

We

surveyed it gloomily, safe in our cabs from the slanting rain. But there is only

one way to size up such a situation. So two brave souls waded in. Muted cries

of anguish were heard as the icy water crept over their ankles and knees and up

their thighs. It looked impossible. Then a further search upstream showed a dim

chance. One car went in. The engine screamed, the wheels slipped, water piled

up against the side (and came in under the door).