University

of Bristol Trans-Continental Expedition 1960 — 61 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| published 23 May 1961 | ||||||||

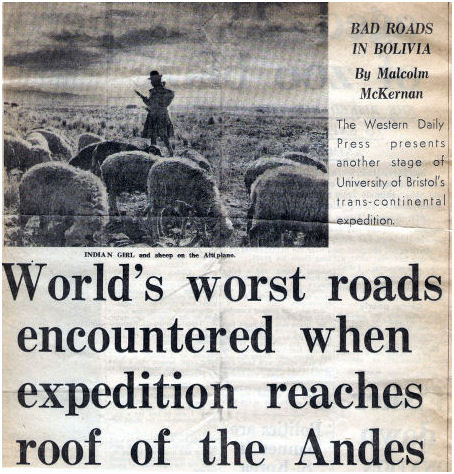

In the beginning the road goes out across the Altiplano leaving behind the sand dunes of Oruro (three hundred miles inland, with snow-covered mountains gleaming behind them). On the South Altiplano and only there, thriving in the cold, dry climate, gros the tola bush, which resembles - and smells like - a tiny cyprusess. It is the only fuel of the Altiplano, there being almost no trees. The intense green of its foliage gives a false idea of vegetation. In between the bushes is dead gravelly soil which bears nothing else. There is always fascination in driving across the Altiplano. The road sweeps away to the horizon, quite straight, and as the horizon rolls back, so the road rolls on - there is always more of it; at each side the land is equally flat, and equally endless, and above, the blue sky curves away to the clouds that fringe the distant snow-capped mountains. Everything is vast; an approaching vehicle will take countless minutes to arrive. It is impossible to judge distances. But it never seems monotonous - perhaps because of the nature of the roads. This is the dry season - for which we should be thankful. The roads must be all but impassable in the wet. But the legacy of the mud remains in the form of deep ruts and rough piles of sharp edged earth. Picking the way Of course, there is no question of driving on one side of the road only, one picks one's way - here, there, and all over the place - frequently leaving the 'road' altogether if the going seems better at the side. (And running the risk of getting caught in the deceptive smoothness which generally means softness). This went on, I suppose, for about 40 or 50 miles, and it took over four hours. There were occasional Indian villages, flat huts made of earth bricks and as effectively camouflaged into their background as the Turkish hill villages. Then we reached the town of Challapata. This is the junction for the road south to Chile, but we were to turn east over the Cordillera Oriental, into the Province of Potosi. Family tragedy Here we had a well-earned cup of coffee; and accumulated a passenger. Bolivian coffee is extraordinarily good, so perhaps we were mellowed, but in any case it would have been hard to resist this story - particularly as we were only five in the cars. Roger, our business manager, being temporarily detained in La Paz. The proprietress of the café interceded with us on behalf of this poor little Indian, who seemed at the time to be carrying little. The story was in a jumbled form, but, clearly, there had been an accident many miles down the road to Potosi, and this man's wife had been killed or injured. He was trying to get to here. There would be no transport that day, could we take him? We had only intended to drive a further 30 or 40 kilometres that night, before looking for a camping place, since in an hour or so, it would be dark; and this place was 120 kilometres away. However, it was obvious that we must take him. It is pleasant to record that our good turn was repaid. We discovered next morning that we had left behind a camera; one car drove back the five hour trip to Challapata and found that the proprietress had kept it for us. Our passenger was a Kechwa Indian, [Quechua] so small and still that his presence in the cab was hardly noticeable. We established quite early that he spoke a little Spanish, but the Indians are not garrulous with strangers and he was in no mood for conversation. We now began to climb into the mountains. Vegetation of a poor kind began to appear. This is llama country; they are unique to this part of the world, and one would swear they knew it. They look like a cross between a camel and a goat, standing around five-foot six inches high, of which two feet is neck. This makes them about as tall as their Indian herdsmen; they look at the world from a human being's angle and do not seem very impressed with what they see. Dignified They have all the dignity and self-importance so infuriating in the camel, but this is compensated by their extraordinary air of intelligence. They have Alsatian ears, constantly erect and vigilant, and their heads move from side to side, not smoothly, but in short sharp movements; nothing escapes them. This is in great contrast to their lords and masters, who are somnolent in appearance and lethargic, being bundled up in blankets and ponchos, and generally seeming dumpy and ungainly. The llama carries his own fur coat of course, and magnificently long and thick it grows. They serve the Indian for wool and meat - most of which he sells - also with dung for fuel, manure and building material. They are also pack animals, being as surefooted as goats, in spite of their size and weight. (In the days of the Spanish conquest it was the llama trains, bells ringing, that brought the unavailing ransom of gold bars over the hills for Atahualpa, the last Inca.) Incidentally concerning the rumour of llamas spitting at their foes; we have not yet found any confirmation of this. Our Indian was becoming more communicative. Suddenly he burst out and told us his story. It was his wife, he said, the wagon had had an accident, and she had hurt her head very badly; his daughter had been killed. He did not think his wife would live either. Badly damaged As it grew dark and we ploughed over the bad road, his sobs became louder. Then he cried out "It is here!" We turned a corner and saw the truck, righted now, but it had obviously careered off the road, scattered a pile of large boulders and turned over. The cab was very badly damaged. It was unloaded, but the common practice is to pile the back high with cargo and sit the passengers on top; in the event of an accident they might be thrown many yards and could have little chance of survival. On such bad roads these truck/buses must be responsible for many serious accidents. We drove on in grim silence the poor man gradually subsiding: "What will happen if my woman dies?" he had cried. Eventually, in total darkness, we came to a small village. This was the place either where his daughter's body had been taken, or where his wife was lying, we never discovered which. Our offers of medical aid seemed to mean nothing to him, he hurried off from house to house until we lost him in the night. So we pushed on a little further and made camp at 11 o'clock. The altitude must have been about 17,000 feet; it was very cold. We pitched our tents and got water from a neighbouring stream; all we needed was a couple of sticks to rub together! But two sticks are exceedingly difficult to find in the Andes, so we made do with the more prosaic petrol stove. Got worse In the morning we had to tackle that road again. And it got worse. It was built on clay - red clay, very picturesque, with green vegetation on the hills, but by no means strong enough to carry heavy traffic. When we won through the clay country we came upon rock. Literally, we drove on it, the road being in layers like a flight of steps. The surroundings had been uninspiring - upland fell country of common type. The only interest had been in the sudden addiction to dry-stone walling, reminiscent of the Lake Country. But now the scenery was truly mountainous. We must have reached 18,000 feet and were on a par with the rows and rows of mountain ranges that stretched away into the blue haze. There were many great cliffs of basaltic rock hanging like curtains, formed by ages-old volcanic outpourings; and the valleys in between were probably up to 2,000 feet deep. Around us - and above! - were enormous boulders, roughly spherical and over 20 feet tall, some of which were used as back walls for peasant huts. Precipitous Among all this precipitous grandeur, small fields had been carved out of the hillsides and were obviously very fertile - after the fashion of broken up volcanic sediment. This was much more our idea of Andean scenery, but it made concentration on the road more difficult. From this point we drove down into Potosi, which has always been an important centre for mining in Bolivia. Here we were lucky. Returning to our car, we found standing beside it, the director of the United Nations base where we were to stay. So there would be no more searching for the right road. The only difficulty was in keeping up with him. He drove a small Citroen at vast (and often dangerous) speed, but had the excuse of wishing to get home before dark since he had no lights! Unfortunately this proved impossible, and for the last hour we drove on one set - ours. The road was much smoother and wider (or this manoeuvre would have been impossible), but was covered in soft gravel and permanently hung about with a five-foot cloud of dust. Exercise Riding in our Gipsy six yards behind and slightly to one side, in order to throw our headlights past his little car, we became the blind ones. At speed up to to 30 miles an hour with the atmosphere yellow and fog-like, and with the necessity of maintaining equal speed with a car of much lower power, this was an interesting exercise in driving - but not one to be recommended at the end of a tiring day.

| ||||||||

|

The

next stage

The

next stage