University

of Bristol Trans-Continental Expedition 1960 — 61 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| published 13 April 1961 | ||||||||

Easter

festivities in Bolivia, two days of widely different ones, illustrating, as perhaps

nothing else could, the divisions in this country. It is the custom in many parts

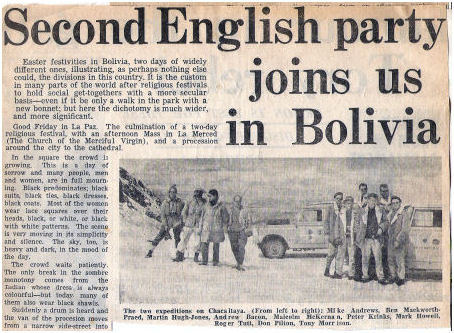

of the Good Friday in La Paz. The culmination of a two-day religious festival, with an afternoon Mass in La Merced (The Church of the Merciful Virgin), and a procession around the city to the cathedral. In the square the crowd is growing. This is a day of sorrow and many people, men and women are in full, mourning. Black predominates; black suits, black ties, black dresses, black coats. Most of the women wear lace squares over their heads, black, or white, or black with white patterns. The scene is very moving in its simplicity and silence. The sky, too, is heavy and dark; in the mood of the day. The crowd waits patiently. The only break in the sombre monotony comes from the Indian whose dress is always colourful - but today, many of them also wear black shawls. Suddenly a drum is heard and the van of the procession moves from a narrow side-street into the square. Three purple banners followed by a few choristers in purple and some in sky-blue, and girls from the Catholic schools. Then the civic band in severe black uniform beating time on drums. The procession stops. Officials hurry out of sight down the line. Ascetic Then movement begins again. First to the drums alone, then suddenly and most impressively, the band bursts into the Dead March from Saul. Almost simultaneously a platform is born into sight, surrounded by soldiers with fixed bayonets - a representation of the Hill of Calvary with a crucified Christ and two weeping Maries. The crowd crosses itself and the men bare their heads. The blackness of the scene is intensified. Everything is very still. Civic dignitaries follow, and detachments from the Army and Air Force in slow march with bayonets fixed. Then comes a glass-sided coffin containing an effigy of the dead Christ, torn and bleeding, lying on purple sheets and purple pillow. The bearers are 16 men in penitents' garb - full purple robes and purple hoods, the eye-holes, like black, blank circles, the only break in the flow from high, pointed cowl to sandaled feet. At each corner stands a tall candle, protected from the wind by a glass shade, and the woodwork is picked out in gold leaf. Behind this platform walks the ecclesiastic party; the archbishop, elderly, ascetic, in scarlet biretta and ermine cape, and his priests intoning the prayer, "Holy Mary, mother of god, pray for us sinners now, and at the hour of our death." Many people are now joining at the side of the procession, which expands to fill its restricted path until no distinction can be made between the procession and the crowd. From above it is a dense mass of black heads slowly following the muffled drums. Fertile Then comes the final platform - the sorrowing Virgin Mary gloriously arrayed in a dress resembling an ecclesiastic robe and lit by eight candles. And the crowd follows, flooding out of the narrow street into the square, picking up adherents like a snowball rolling down a hill. At first it seems they are all women, but, in fact, men also are present. No Indian joins in; they content themselves by sitting on the steps in front of the cathedral waiting for the procession's return. It continues along a route perhaps three miles long, al the way thickly lined with dark, sorrowing crowds, and back to the cathedral to disperse. The next day, Easter Saturday, we spent at Lake Titicaca. Nothing could have been more different from the Friday; the sky was blue with little white clouds, there was a breeze, and the sun shone. This was a new road for us and it seemed to have an unfair ration of flowers - or perhaps it was just the sun after the rainy season. There were about six different yellow ones, varying in shade from primrose to rich ochre, some delicate blue ones like tall harebells, and several red varieties including, surprisingly, a geranium growing out of a garden wall. But the most popular colour was yellow, very cheerful and springlike. This was the most fertile part of the lakeside lands. The crops were six inches to a foot taller, much more densely sown, and the heads heavier and more promising. Many of the cottages had doors and windows (in itself surprising) and quite a number had corrugated roofs instead of the almost ubiquitous thatch. Also the people had more money to spend than the Indians we had previously met . . . and were spending it in the usual way. For today was a holiday, as will shortly be seen. Our expedition was a combined one. Two days before a Cambridge University Trans-American Expedition had pulled into La Paz, and occupied, in our temporary absence, some of the quarters put at our disposal by the Ferrocarril Antofagasta Bolivia, the once English-owned (and still English-managed although nationalised) railway company. This is an expedition of four men, two veterinary surgeons, Martin Hugh-Jones (whose sister had studied at Bristol and was known to three of our members) and Andrew Bacon, an engineer Ben Mackworth-Praed and a photographer Mike Andrews. They are driving from Tierra del Fuego, in the far south of America, to Alaska, in the far north of North America - the longest north-south journey in the world; en route they are carrying out studies in animal husbandry in the various countries. We had expected them rather earlier, and in fact they were a month late in Bolivia - delays can easily mount up - but were otherwise in good condition. It seems that university rivalry is less keen at this distance from home and we were able to get on to amicable terms quite quickly! (Incidentally, Bolivia is flooded with expeditions from England this year; later a combined Oxford-Cambridge group will come to do research in cosmic rays, and there will also be a Reading University Mountaineering Expedition). The Cambridge party told us about the Argentine and Chile, which we will not visit, and we were able to reciprocate with stories of the Middle East, India and Singapore - so honour was even! Indian band The photographers of the two expeditions wished to take some shots on Lake Titicaca, and Hugh-Jones and I accompanied them. We went to San Pablo, a small village that has a ferry across a tongue of the lake. The ferries are sail-powered, except when close to land, when the sails are lowered and poles used. The design is influenced by the fact that cars and even large lorries must be transported - one per boat. Their shape is that of an old flat-iron, the vehicles being run on and off at the stern (with two lines of men and boys holding the boat in position against the rude stone pier with two long chains, and shouting out instructions and encouragement to the driver). The boats have grandiose names, Bolivia, Santa Maris, Lusitania, this last being particularly appealing. As we worked with our cameras at the lake-side, behind us in the village an Indian band began to play. We turned to see a crowd of people tumble out of a house and proceed merrily, but far from steadily up the hill, following the musicians and a large Bolivian flag. (Broad horizontal stripes of red, yellow and green; red for the blood of the martyrs, yellow for gold and the mineral wealth, green for the fields.) Today was the day for fiestas and parties. Lent was considered over and it was everybody's duty to enjoy himself. We came across three parties in that village alone, and could hear another developing cheerfully across the lake at the other end of the ferry. The life of the Indians will form my next report; now it only needs to be said that it is very monotonous and has few material rewards. But there has grown up a tradition of behaviour at fiestas. The status of the Indian seems to be partly based on how much money he is able to spend on these occasions and this means how much chicha he is able to buy and consume. Chicha is an extremely powerful alcoholic drink common in many South American countries. In Bolivia I is made in two ways; by distillation of liquer from sugar cane - a relatively high-class product (actually called pisco); the second method is from maize and the process entails pre-mastication and expectoration, the subsequent liquid is fermented and distilled. It is advisable to avoid too much consumption of this type! We followed the first party in its uncertain, but happy, progress up the hill. At fiesta time the men put aside their ordinary clothes and dress as colourfully as the women; they wear large gaily striped ponchos (a diagonal blanket with a hole in the centre of the head), pigtails of artificial hair, and, perched on top, tiny home-made party hats. The overall effect is quite astonishing. Revels We were particularly intrigued by the bass drummer in this band, an enthusiastic, but handicapped, musician; his instrument was being carried horizontally in front of him by two equally inebriated friends. Whenever he was able to sight it properly he made a wild lunge with a drumstick - this made a satisfactory, if off-beat noise, but the impact only added to the lack of balance of the bearers. As with all the music, the effect was mainly noteworthy for enthusiasm, not accuracy. This group ended up in a field and a semi-orderly dance developed. We took some photographs and returned to the centre of the village. Here a much more bacchanalian revel was under way just outside the church whose wide open door and decorated illuminated alter seemed something of a reproach. The order of the day is that the women all sit together in a circle on the ground and the men stand apart. Occasional encounters take place in the middle, naturally. There was some attempt at dancing, but the dance chosen, the cueca, is very fast and intricate and quite beyond the powers of the revellers. Bottles of chichi passed from hand to hand and some people even had jugs full. It is a regrettable fact that the women drink as much as the men and can stand the effects no better; the sight of a semi-drunk mother suckling a child is not very pleasant. The mod changes from an offensive bonhomie, through a maudlin, weak-knee'd stage, to one of aggressive self-assertion - the familiar pattern. We had the greatest difficulty in persuading a man in phase three that we had no desire to buy a bottle of chicha for 6,000 bolivianos (about 3s td). "Yes", we said "we know it would cost much more in England (he insisted on saying Germany), ut no lo queremos - we do not want it!" When it reached the point that he threatened to bring his friends along, we jumped into the car and drove off. The people here have been spoiled by their closeness to foreigners and tourists. Everything has a value and the money must be extracted. This is not so in the more remote villages. There the Indians would play their flutes and drums for our tape-recorder with great good humour and only ask to hear the play back (they are always delighted, no matter what the quality). They press on you far more drink than common sense allows and photography is made difficult only by their determination to be I'in on the act.' But in today's villages, no sooner had a shutter clicked an unknown group than some man would appoint himself their business manager and come to extort the fee. We felt like unwanted outsiders, and eventually the afternoon became so unpleasant that we were forced (once again) to an ignominious retreat with the cry of gringos (foreigners, not a polite form) - normally only heard from small children - echoing after us. The place was beautiful and prosperous, but the people were not like the Indians of the area where we had spent the last three weeks; here 'civilisation' seemed to have some degenerating effects. Tiring But in any case we had to leave quite early to go to a rendezvous at the top of a mountain. This is Chacaltaya, 15 miles from La Paz, and some 17,500 feet high. It is not the highest nearby peak (some are well over 20,000 feet), but has a road to within a few hundred feet of the summit, which must be one of the world's highest roads, and it certainly possesses the world's highest ski-slope. The other six members of the two expeditions were waiting for us and we had intended to test our camping and sleeping equipment under really severe conditions. But we discovered that we had been invited to stay in an empty ski-chalet, so the tents were not used. However, it was below freezing inside, and we had the pleasure of proving that our sleeping bags were more than adequate. Unfortunately our lungs were not - it must be really difficult finding the energy for ski-ing at that altitude. We all, more or less, suffered from lack of oxygen, breathing was deep and laborious, all exertion tiring, and worst of all, it was very difficult to get to sleep. But the drive up, and the view and the general atmosphere next morning, made it worthwhile. We climbed the mountain at night, a rough road and times a dangerous one, with deep drops at the side. As we got higher patches of snow reached down like fingers to greet us, blueish against the warm coloured rocks. Gradually the snow covered everything and its whiteness was established - it looked like the traditional Christmas cards, glistening in the headlights. Later a very large full moon rose, and the crisp snow threw back its light. Unfortunately it was too cold to stay outside admiring the prospect. In the morning the air was still cold and the sun shone with that overall intensity peculiar to snowy places. So we went out to admire the view and count mountain tops. We also had an inter-varsity snowball fight, which left us all breathless … but gave the delighted photographers some very good material! | ||||||||

|

Easter

in Bolivia

Easter

in Bolivia