WHO

WAS ISAMBARD KINGDOM BRUNEL?  Marc

Isambard Brunel his father, an engineer was born in Normandy, France. His mother

Sophia was the orphan daughter of William Kingdom a naval contractor from Plymouth

in the far southwest of England. Marc and Sophia met in Paris, France in 1792

where she had been sent by her eldest brother and guardian to learn French. After

a brief romance they were separated by the upheavals of the French Revolution

and Marc chose to flee to America where he worked as an engineer and designer,

eventually being given the post of Chief Engineer in the city of New York. After

a series of entrepreneurial business affairs lasting six years Marc Brunel travelled

to England and found Sophia in London. Then following his trade as an engineer

and businessman Marc settled in Portsea a district of Portsmouth, a naval dockyard

town about 70 miles /112 kms south from London. Marc and Sophia married in London

in November 1799 and Portsea became their first home. It was some time later that

the town became the resting place of the iconic British warship HMS Victory. Marc

Isambard Brunel his father, an engineer was born in Normandy, France. His mother

Sophia was the orphan daughter of William Kingdom a naval contractor from Plymouth

in the far southwest of England. Marc and Sophia met in Paris, France in 1792

where she had been sent by her eldest brother and guardian to learn French. After

a brief romance they were separated by the upheavals of the French Revolution

and Marc chose to flee to America where he worked as an engineer and designer,

eventually being given the post of Chief Engineer in the city of New York. After

a series of entrepreneurial business affairs lasting six years Marc Brunel travelled

to England and found Sophia in London. Then following his trade as an engineer

and businessman Marc settled in Portsea a district of Portsmouth, a naval dockyard

town about 70 miles /112 kms south from London. Marc and Sophia married in London

in November 1799 and Portsea became their first home. It was some time later that

the town became the resting place of the iconic British warship HMS Victory. Isambard

was born in Portsea

in turbulent times on April 9th 1806. It was less than six months after the battle

of Trafalgar when the combined Spanish and French fleets were beaten by the British

Navy and Vice-Admiral Nelson died on HMS Victory. Marc continued working at the

dockyard as an engineer and businessman until the prospect of further contracts

dried up. The family then moved to London where he opened other businesses including

one with another naval dockyard. The young Isambard grew up in a heady mix of

engineering and the ups and downs of a business life. He spent two years studying

in France including a short apprenticeship with a famed watchmaker, Abraham Louis

Breguet before joining his fathers' office at the age of sixteen. By twenty he

was the engineer in charge of building a tunnel under the River Thames between

Rotherhithe and Wapping in the eastern part of London. An accident during tunneling

in 1827 almost cost Isambard Brunel his life and led to a long delay with the

project. It was a turning point in his career. Recuperation was followed by a

period of new ideas and offers, some outside London. Brunel visited many places

in the heartland of the British Industrial Age observing in some and finding work

in others.  Eventually

a challenge for a bridge design arose in Bristol an historic city and port 120miles

/ 192 kms miles west of London. Eventually

a challenge for a bridge design arose in Bristol an historic city and port 120miles

/ 192 kms miles west of London. Modern

Bristol is built on either side of a tidal river, the Avon, often known as the

'Bristol Avon' to separate it from others of the same name. The origin of the

city goes back over a thousand years to a settlement which was known at first

as Bricgstowe from the meaning 'place of the bridge'. Later this changed

to Bristowe and the town developed in a small area of about 26 acres /10.5

hectares enclosed by defensive walls between the Avon and a small tributary, the

Frome. The port filled with a forest of masts became the focal point of a city.

The scene was completed by many fine churches, businesses and the homes of wealthy

merchants. Outside the city walls the land was still rural until the late 1700s

when the wealthier residents began to build homes with now famous classical Georgian

architecture on heights overlooking the old city. These grand residences were

established around the village of Clifton close to the point where the Avon passes

through a gorge . The

Avon Gorge The Avon river rises in low hills to the northeast of Bristol and

after passing through the city flows another 7 miles until it reaches the estuary

of the River Severn. In turn the Severn flows into the Bristol Channel a huge

inlet of the sea. The tides in the channel are among the most extreme

in the world and average 43 feet / 13m. Any large ship leaving the port of Bristol

has to pass down the Avon at high tide to reach the sea. Some of the route is

through a striking limestone gorge flanked in a few places by steep cliffs and

in others by heavily tree-clad slopes. In the 18th century the idea of a bridge

across this gorge was no more than a dream. William Vick a foresighted wine merchant

had such a dream in 1753 and bequeathed a sum of £1000 to grow by compound

interest to £10,000 at which time. or so he thought, it would be sufficient

for the project. The money was left in the care of The Merchant Venturers, a Guild

or more simply a Society incorporated by law to ensure the exclusive rights for

trading of its members within the city. By 1829 the Vick bequest had grown to

£8000 and the Merchant Venturers formed a committee to call for designs

for a bridge. Isambard Brunel was 23 and he was quick off the mark with an ambitious

but meticulously calculated plan. THE MERCHANT

VENTURERS AND THE PORT OF BRISTOWE  The

Society of Merchant Venturers in charge of the bridge at the time has a history

dating back to the 15th century and perhaps much earlier. In those days Bristol

was growing rapidly in importance through its trading with Ireland, mainland Europe

and the Mediterranean. City merchants were financing the building of ships and

fitting them out with crews and provisions to make wild fortunes. The port bustled

with activity and the men who ran the city, who were mostly the merchants, formed

a Guild to keep the trade to themselves, or in effect to keep it for the city

and not let it loose to outsiders. In 1552 the Guild received a Royal Charter

from the very young British King Edward Vl who was the third of the Tudor line.

Edward Vl reigned between 1547 and 1553 and is probably best remembered

for assuring Protestantism in Britain. The Charter Edward Vl granted to the 'Merchant

Venturers of Bristol' when he was only fifteen gave them a name and a coat of

arms. Today the Guild is known as the Society of Merchant Venturers and

the present members can look back to over 500 years of extraordinary history. The

Society of Merchant Venturers in charge of the bridge at the time has a history

dating back to the 15th century and perhaps much earlier. In those days Bristol

was growing rapidly in importance through its trading with Ireland, mainland Europe

and the Mediterranean. City merchants were financing the building of ships and

fitting them out with crews and provisions to make wild fortunes. The port bustled

with activity and the men who ran the city, who were mostly the merchants, formed

a Guild to keep the trade to themselves, or in effect to keep it for the city

and not let it loose to outsiders. In 1552 the Guild received a Royal Charter

from the very young British King Edward Vl who was the third of the Tudor line.

Edward Vl reigned between 1547 and 1553 and is probably best remembered

for assuring Protestantism in Britain. The Charter Edward Vl granted to the 'Merchant

Venturers of Bristol' when he was only fifteen gave them a name and a coat of

arms. Today the Guild is known as the Society of Merchant Venturers and

the present members can look back to over 500 years of extraordinary history.  In

1497 The Merchant Venturers funded John Cabot who was born in Italy as Giovanni

Caboto in 1450, or so it is thought, and who set out from Bristol and discovered

Newfoundland - he arrived in the Americas only four and a half years after Columbus

reached the Bahamas. Merchant Venturers or their agents brought the brilliant

red Nonesuch flower In

1497 The Merchant Venturers funded John Cabot who was born in Italy as Giovanni

Caboto in 1450, or so it is thought, and who set out from Bristol and discovered

Newfoundland - he arrived in the Americas only four and a half years after Columbus

reached the Bahamas. Merchant Venturers or their agents brought the brilliant

red Nonesuch flower  to

Bristol from somewhere in the Mediterranean and it was established in Bristol

by the 16th century. It became known as the Flower of Bristowe or the Campion

of Constantinople after an earlier connection with the Middle East. In 1631 the

Merchant Venturers financed the voyage of Captain Thomas James to find the Northwest

Passage in the icy sea across the top of the Americas. He was not successful but

is remembered there by a bay named after him. Then came one of the darkest times

in the history of the Society when the trade in black slaves from western Africa

expanded rapidly. Late in the 1600s the Bristol merchants challenged an established

slave trading company and took the lead with slaving and sugar plantations in

Caribbean islands and as many as 2000 slaving ships were fitted out in the port.

Some Bristol families made immense fortunes and their names have lived on as symbols

of a mixture of philanthropy and suffering. to

Bristol from somewhere in the Mediterranean and it was established in Bristol

by the 16th century. It became known as the Flower of Bristowe or the Campion

of Constantinople after an earlier connection with the Middle East. In 1631 the

Merchant Venturers financed the voyage of Captain Thomas James to find the Northwest

Passage in the icy sea across the top of the Americas. He was not successful but

is remembered there by a bay named after him. Then came one of the darkest times

in the history of the Society when the trade in black slaves from western Africa

expanded rapidly. Late in the 1600s the Bristol merchants challenged an established

slave trading company and took the lead with slaving and sugar plantations in

Caribbean islands and as many as 2000 slaving ships were fitted out in the port.

Some Bristol families made immense fortunes and their names have lived on as symbols

of a mixture of philanthropy and suffering.

When

in 1829 the Merchant Venturers called a competition for designs for a bridge across

the Avon gorge Isambard Kingdom Brunel was convinced it had to be a suspension

bridge. He submitted four designs one for each of several locations along the

gorge. Thomas Telford another bridge builder was asked to judge the competition

and rejected all the designs. Telford was then asked for a design and the story

took several twists until Telford too, was rejected. A second competiton in 1830

led to a fresh design from Brunel and he was declared the winner. Work commenced

on July 1831 and ceased abruptly in October due to riots by citizens opposed to

all manner of problems. [search Bristol Riots 1831]. After the Riots other

engineering plans took Brunel away from the bridge construction which was already

stalling due to cost. Work on the bridge began again in 1836 though was not completed

until after some changes to the plan after his death. A

MARITIME CHALLENGE Isambard Kingdom Brunel became established in Bristol at

a propitious time. Slaving had been legally abolished. The city also faced challenges

from other ports especially Liverpool in the northwest where the docks opened

to the sea and were not subject to the silting or the tidal whims of an estuary

like the Avon. At low tide in the early days the ships were left on the mud beside

the river and reached by wooden walkways. It was not until 1803 that a docks company

was formed under pressure from The Merchant Venturers and locks were built so

between tides water remained in the basin or the Floating Harbour or 'Float' as

it was known. Brunel was given the job of improving the docks but the Riots delayed

many of his plans. Railways

were seen as the next step for economic advancement all over Britain and Bristol

could not allow Liverpool to get ahead in the race to rail. The Liverpool and

Manchester Railway led the way when it was opened in 1830 and Bristol was still

twelve hours journey time in good conditions to London by horsedrawn coaches known

as 'the flying coaches'. A group of Bristol businessmen including The Merchant

Venturers faced up to the challenge and in 1832 formed a committee to consider

making a railway from Bristol to London. They needed a survey, an engineering

plan and huge financial backing. Brunel who was already working to improve the

Bristol docks got the job. The company was founded in 1833. Brunel's engineering

star rose quickly. and at a meeting of the company in London in 1835 he proposed

an extension of the route to New York using company owned passenger ships from

Bristol. The idea was visionary and exciting. Within a year a new company, The

Great Western Steamship Company, was founded. The Company financed docks and two

large ships. One, the Great Western was a side-paddle steamboat built

of oak and with sails. The other, the SS Great Britain or 'Steamship Great

Britain ' was built of iron and although it had masts was designed to be driven

by steam and a single huge propeller with a diameter of 15.5ft / 4.7m. Part of

the challenge facing Brunel was to create a ship which could cross the Atlantic

with sufficient coal on board to avoid re-fuelling. Such considerations are of

paramount importance for modern continent hopping aircraft and Brunel's vision

was at the forefront of the revolution.

| THE

SS GREAT BRITAIN | | Length

322 ft/ 98.14m overall or at 107 yards is just shorter than the minimum length

of an international football pitch | | Breadth

max/ 50.5 ft / 15.39m | | Weight

of iron 1,040 tons / 1,056.5 tonnes | | Dry

weight of the engine and boiler 520 tons / 528.25 tonnes |

| Displacement

3,675 tons / 3,733.3 tonnes |  For

the construction of the Steamship Great Britain the Great Western Steamship

Company built a complete site in the Bristol docks. It was known as Wapping Wharf.

The cost was around £53,000 and because the weight of the vessel was thought

to be too much for a slipway, the Company built a special dry dock. For

the construction of the Steamship Great Britain the Great Western Steamship

Company built a complete site in the Bristol docks. It was known as Wapping Wharf.

The cost was around £53,000 and because the weight of the vessel was thought

to be too much for a slipway, the Company built a special dry dock. At first it was known as the Great Western Dock and then later as Wapping Dock.

Two hundred gas burners were installed so work could continue around the clock.

This special

dock is the one still used today by the ship. The impression on the right gives

some idea of the tight fit between the dock sides and the hull.

At first it was known as the Great Western Dock and then later as Wapping Dock.

Two hundred gas burners were installed so work could continue around the clock.

This special

dock is the one still used today by the ship. The impression on the right gives

some idea of the tight fit between the dock sides and the hull.

With great celebrations at the dockside the SS Great Britain

was launched by Prince Albert the consort to Queen Victoria of England on July

19th 1843. One schoolboy said in his account ' he (the Prince) received several

addresses, one from the Clergy and a beautifully chased gold snuff box from the

Society of Merchant Venturers. He was accompanied by the troops of the Yeomanry

and in his carriage by the Mayor, Mr.Gibbs, Lord Somebody and Somebody else....'

After a bad start when the ship stuck in the dock at the launch and later in lock

gates of the Floating Harbour, her career was a wonderful melange of success and

tragedy. The

SS Great Britain made many long voyages with destinations such as New York

and achieved 'first across the Atlantic' by a screw/ propeller driven

ship. Then came voyages to Constantinople / now Istanbul carrying troops to the

Crimean war and then to Melbourne, Australia. In 1882 the great iron steamship

was converted to sail only for carrying cargo. The engine was removed, the hull

was clad in wood and the ship was registered simply as the 'Great Britain'.

After conversion the Great Britain made two voyages south from Liverpool

to the notorious Cape Horn / Cabo de Hornos the southermost point of the Americas

and on to San Francisco on the east coast of the USA. The Great Britain made two

return voyages around the Cape and it was on a third outward journey, also around

the Cape to Panama that disaster struck. The

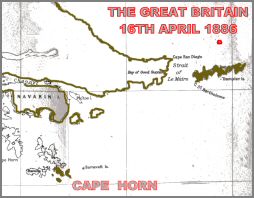

Final Voyage The Great Britain left Cardiff in the Bristol Channel

under the command of Captain Henry Stap on February 6th 1886 bound for Panama

with a cargo of coal. The route lay southwards around Cape Horn. On March 25th

they were off east coast of South America about 260m / 416 kms south of Rio de

Janeiro Brazil in bad weather when a small fire started in the cargo. It was soon

extinguished and for a short while the voyage continued normally for the latitudes.

The Great Britain sailed south until on April 16th she was hit by hurricane force

winds sending seas breaking over the decks.  Captain Stap and his crew had reached 54° 25´ south 64° 28´

west in a position just north of Isla de los Estados as it is known today. In

the days of the Great Britain the island was named Staten Island or even

earlier as Staten Land. It is a long, narrow island extending east from Tierra

del Fuego, the southermost land of South America and separated from it by an 18.6

miles / 30 km wide strait

named after Jacob le Maire a Dutch navigator. Le Maire was there in 1615 in in

a 360 ton ship the Unity or Eendracht and in the company of smaller ship

the Hoorn commanded by Willem Schouten and named after his birthplace

in Holland. The expedition lost the Hoorn in an accident and when they

rounded the cape into the Pacific in January 1616 Schouten named it Hoorn.

Captain Stap and his crew had reached 54° 25´ south 64° 28´

west in a position just north of Isla de los Estados as it is known today. In

the days of the Great Britain the island was named Staten Island or even

earlier as Staten Land. It is a long, narrow island extending east from Tierra

del Fuego, the southermost land of South America and separated from it by an 18.6

miles / 30 km wide strait

named after Jacob le Maire a Dutch navigator. Le Maire was there in 1615 in in

a 360 ton ship the Unity or Eendracht and in the company of smaller ship

the Hoorn commanded by Willem Schouten and named after his birthplace

in Holland. The expedition lost the Hoorn in an accident and when they

rounded the cape into the Pacific in January 1616 Schouten named it Hoorn. If

the crew of the Great Britain even saw Staten Island through the bad weather,

it would have appeared totally uninviting as a spectacular line of pinnacle peaks

set in a mountainous land. It seems that Captain Stap was making for the lee of

the mainland to pass through the narrow Le Maire strait to take him on course

westward to Cape Horn. The

storm subsided and the crew took stock of the ship. The coal cargo had shifted

and the Great Britain was listing to port. The crew shovelled the coal

into its correct place and righted ship, very luckily so it happened, as the Great

Britain was hit by yet more gales and the foremast and topgallant mast were lost.

Such calamities were not the fault of the crew, Captain or the Great Britain although

the ship was probably overloaded. The events they faced were the norm for 'rounding

the Horn' in sailing ships. The men were exceptionally tough and with bravery

faced extraordinary conditions without having the trappings of modern navigation,

communication or survival capsules. The entire region was the graveyard of many

fine ships and some of their hulks still rest in isolated bays around the coast. The

Great Britain failed to pass the Cape and after repeated pressure from

the crew and in the face of tempestuous seas Captain Stap decided to turn about.

On May 13th 1886 they headed northwards for the haven of Stanley Harbour an enclosed

arm of the sea in the Falkland Islands / Malvinas, a group of islands roughly

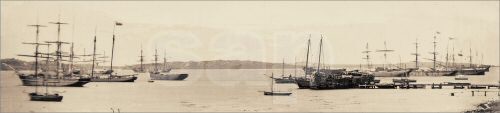

482 miles / 77kms from the Cape. The Falklands, Malvinas

or Malouines as sailors variously knew them include two main islands East and

West with about 700 smaller islands and islets. Port Stanley or simply Stanley,

the main town is on the East Falkland

| Stanley

harbour in the 1880's |  | |

The Great

Britain arrived in the Falkland Islands / Islas Malvinas for repairs on 24

May 1886. Later she was declared a wreck and remained in the islands until 1970.

A salvage team funded by a British businessman, Jack Hayward, now Sir Jack Hayward

[knighted 1986], and spearheaded by Ulrich Harms' salvage specialists from Hamburg

Germany then partnered with the British firm Risdon Beazley, recovered the wreck.The

hull was towed on a pontoon to Avonmouth a port in the Bristol Channel and then

towed by tugs up the river Avon. The story of the salvage is on this website.

| TWO

EXTRAORDINARY MOMENTS IN HISTORY |

|

| April

28th 1970, South Atlantic Ocean One hundred and sixty four years after Brunel's

birth and one hundred and twenty seven years after launch in Bristol, the Great

Britain is towed home on a pontoon. |

|

July 5th 1970,

Bristol At high tide in the Avon gorge the Great Britain passes under the

Clifton Suspension bridge for the first and last time. As a memorial to Brunel's

skill the Great Britain was afloat in her own right and only under the control

of tugs. One

hundred thousand people lined the gorge, docks and the bridge for this special

moment. | |

| POSTSCRIPT

| | Marc

Isambard Brunel was knighted - given the title 'Sir Marc' in 1841. He died

in 1849 | | Isambard

Kingdom Brunel died in 1859. Father and son are buried in the preserved Victorian

cemetery at Kensal Green in north London, England. | |

The present members of the Society of Merchant Venturers are still wealthy.

The city has grown to around 400,000 with employment in new industries. The Merchant

Venturers contribute to many charities including the SS Great Britain Trust. |

| The Steamship[SS]

Great Britain attracts over 100,000 visitors every year |

| THE CLIFTON

SUSPENSION BRIDGE was not completed in Brunel's lifetime. His winning design

of the 1830's was modified and more funds had to be raised before it was completed

and opened in 1864. Today the bridge is maintained under the care of a special

Trust. It is still open to light traffic and 'tolls' or payments to use the bridge

cover the costs of keeping the structure in good condition. The bridge has become

a symbolic landmark for Bristol and the best known memorial to Isambard Kingdom

Brunel. | | The

total span from the centre points of the supporting piers is 702ft /214m |

| The total

length of the supporting chains from the anchorages on each side of the gorge

is 1,352ft /414m | | The

height from the level of high tide is 245ft / 76m | |

| |

| Two pictures

by Tony Morrison from the 1950's. The Clifton Suspension Bridge from the Clifton

or northern side of the gorge and the City Docks before they began the inevitable

decline. Here a small trading ship from Götenborg is unloading and in the

background one of the Bristol Channel steamers for carrying passengers in the

Channel and south coast. This is the Empress Queen, built in Scotland in

1940 with a length overall of 269.5 ft / 81.9m, so shorter than the SS Great Britain

by 53ft / 16.1m. By the 1950s the passenger trade was unprofitable and the Empress

Queen was sold to a Greek company and left Bristol in April 1955 |

| |

| The

editors realise that many important and famous names of the time have been omitted

from this brief account. Thomas Guppy, Antony Gibbs, William Patterson and Sir

Daniel Gooch to name but a few. These and many more were vital cogs in the Brunel

story and we recommend the biography Isambard Kingdom Brunel by L.TC Rolt [1957]

as a fascinating story full of background info for his life.

Special thanks are given to the inspiring work by Grahame Farr 'The Steamship

Great Britain' Published in 1965 by the Bristol Branch of the Historical Association,

The University, Bristol | Tony

and Marion Morrison who contributed to this Feature story made two visits to the

Falkland Islands / Malvinas in 1969 and 1970. Tony filmed the salvage of the SS

Great Britain for BBC Television and Marion was reporting for the Observer

newspaper, London. Tony, Marion and BBC producer Ray Sutcliffe were suddenly involved

with the dramatic rescue operation late in the afternoon of April 7th 1970 when

an exceptional gale struck the salvage flotilla.

|

|

| The

text and most of the images are © Copyright |

| For

any commercial use please contact | | |

| THE

NONESUCH - FLOWER OF BRISTOL |

| AN

EMBLEM FOR ENTERPRISE | | |