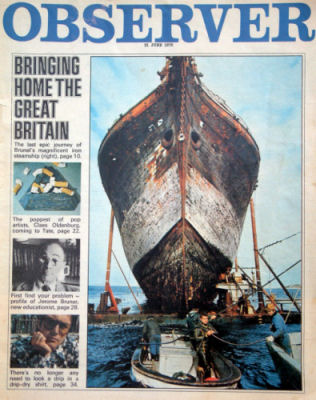

Bringing Home the Great Britain An eyewitness account for The Observer, London, England | ||||||||

THE

GLORY THAT WAS THE GREAT BRITAIN - BY MARION MORRISON 1970 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

Many times in its 127 years of life Isambard Kingdom Brunel's great iron ship ss Great Britain has had to fight for survival - from difficulties at her launching at Bristol to her grounding off Ireland in the early days, and the many stormy passages in the Atlantic and Pacific. Once at rest in the Falkland Islands, where she ran for cover in 1886 after being damaged by a storm, a quiet, unnoticed end seemed certain. But with the successful salvage operation the majestic history of the Great Britain continues. Early on 6 April this year, the ship floated again, after almost 33 years on the sand of Sparrow Cove, a beached hulk, retired even from its earlier ignoble role of floating warehouse. By 4.30 in the afternoon the salvage experts and tugs were fighting to control the vessel against a force 11 gale. Shore lines had been rigged before pumping started, but they were light cables and for a few tense hours the Great Britain was in danger of breaking free. The only safe solution was to stop the pumps and allow the ship to settle again, to wait for better weather. When the Great Britain ran for the Falklands in 1886, damaged by a fire and partially dismasted by a fierce gale she had seen 41 years' service: pioneering Atlantic crossings, carrying immigrants to Australia and troops to the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny; and finally, as a sailing ship, carrying coal to the Pacific coast of the Americas. Disaster struck on her 47th voyage as she was rounding Cape Horn, and once in Port Stanley harbour, in the Falklands, she was written off as a wreck. The Falkland Islands Company bought the hulk and used if for storing wool until 1937, when it made its sad journey to Sparrow Cove. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

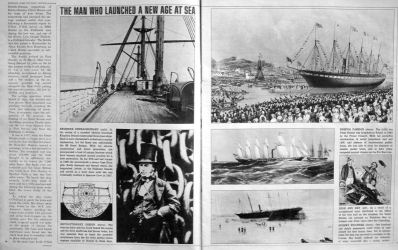

The Glory That was the Great Britain Launched at a ceremony attended by Prince Albert on 19 July 1843, the ship marked Britain's resurgence to great maritime power. Brunel's genius created a ship to dominate maritime technology. The iron-built Great Britain was the forerunner of all modern ships: the first ocean-going ship driven by screw propulsion and the first with the remote-indicating electric log. It was the first ship capable of lowering all masts in a head wind, first with a double bottom, first with watertight bulkheads. As technological spin-off of his achievement, the first shipyard intended to work iron had to be constructed and the steam hammer had to be invented to cope with the materials. Although Brunel's later 24,000 ton Great Eastern was the largest afloat until the turn of the century, the Great Britain on her 15 day maiden voyage to New York in 1845 was almost three times the size of any previous merchant ship - 320 feet long, and 51 feet in the beam, with an overall tonnage of 3,600. The six masts named after the weekdays from Monday to Saturday, were reduced to five in 1847, and in 1853 first to four and finally to three. When eventually she was converted to a full sailing ship in 1882, a wooden sheathing was fitted, though no one quite knows why; possibly it was to protect the hull against damage by lighters in the Pacific. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

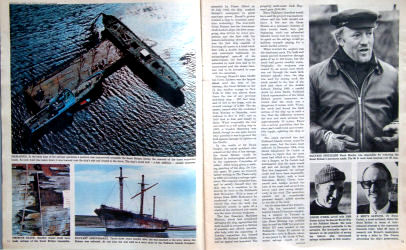

In the words of Dr Ewan Corlett, the naval architect who conceived the idea of her salvage, the Great Britain 'could be likened in technological advance to the supersonic Concordes of today'. After being given a striking painting of the ship, Dr Corlett spent 20 years on research before writing to The Times early in 1968 advocating a salvage operation. The response surprised him and to satisfy himself that the ship was in a condition to be moved, he went to the Falklands that November. With a team of divers from HMS Endurance he conducted a survey that convinced him that the hulk was relatively sound, in spite of a crack on the starboard side which was the most obvious weakness. The San Francisco Maritime Museum, which had considered salvaging the ship, agreed that the hulk should be returned to Britain if possible, and offered considerable help with the organising. A London committee was formed under Mr Richard Goold-Adams, and an appeal was launched. The property millionaire Jack Hayward gave £150,000. Many Falkland Islanders would have said the project was madness: others said the hulk should not leave. A few saw the Great Britain as a necessary element of their tourist trade, now just beginning, while one influential islander noted that the money to be spent on the salvage would go halfway towards paying for a much needed airstrip. What worried the sceptics was the starboard crack. The hulk and masts proved themselves through gales of up to 100 knots, but the crack had grown steadily worse. Originally, the weakness was caused by an access door which was cut through the main deck stringer (plank) when the ship was used for storing wool; the crack spread to the base of the keel just short of the double bottom. During 1969, a careful check by John Smith, Falkland Island representative of the Great Britain project committee, revealed that the crack was a dangerous 8 inches wide. Worse, the crack had forced the back section of the ship up in such a way that the difference between the bow and stern sections was approximately 13 inches. There was a serious possibility that the stern part could twist and eventually topple, splitting the ship in two. The crack survived the last Falkland Islands winter, worst for many years, but the main mast suffered. In December 1969, John Smith telephoned Dr Corlett in London to report that the main mast had tilted in a gale. There was a danger, as Dr Corlett had anticipated, that the mast would fall and cut through the deck. Had this happened, the salvage could well have been impossible, and John Smith, with a local fisherman, Mickey Clarke, hammered new wedges around the base of the mast and secured the heavy yard that swung dangerously in the wind. The operation, carried out at considerable personal danger, added months to the life of the hulk. On the other side of the Atlantic, the 724 ton converted stern trawler Varius II was just completing a mission to Victoria in Guinea, in West Africa, when Captain Hans Hertzog was notified that he and his 2,667 ton pontoon Mulus III were needed in the Falklands. Varius II arrived in Montevideo early in March, where it was joined by Mr Leslie O'Neil, senior salvage expert of the British-German consortium of Risdon Beazley-Ulrich Harms, and his team of four divers. The consortium had accepted the salvage contract earlier this year, following a favourable report by O'Neil. O'Neil served on HMS Exeter in the Falklands area during the last war, and one of his divers Lyle Craigie Halkett, is a Falkland Islander. The flotilla was also joined in Montevideo by Horst Kaulen from Hamburg, an Ulrich Harms specialist in submersible pontoons. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

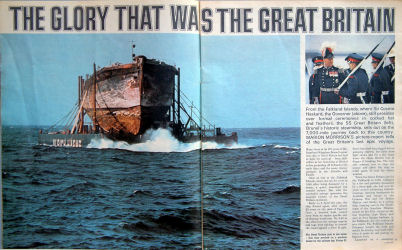

The flotilla arrived in Port Stanley on 25 March, after twice being delayed by gales on the 10 day journey to the South Atlantic. It was a rare scene for the islanders, accustomed to fishing trawlers, small passenger boats and a few tankers, as the immensely powerful tug moved alongside the East Jetty pulling the massive pontoon, 265 feet by 80 feet on a short tow. The salvage operation, which lasted 21 days, was divided into four phases. Most important was patching the hulk, repairing the crack, and removing all masts. Then, in sequence, came the submersion of the pontoon, the floating of the Great Britain and the lifting operation. Finally there was the tow from Sparrow Cove to Port Stanley and from the Falklands to Britain. It was in 1937, when the Great Britain could no longer serve as a wool hulk, that the then Governor, Sir Henniker Heaton, opened a campaign to have her returned to Britain. The estimated cost was about £10,000 and the hulk thought to be sufficiently seaworthy to be towed the 7,000 miles home. But funds were not available and the Great Britain was taken from Port Stanley to Sparrow Cove, a tiny bay four miles away. To beach the ship securely, holes were made in stern and bow with crowbars and during the following years water filled the lower levels of the hulk. To refloat the ship, Leslie O'Neil had to patch the holes and mend the crack. His divers spent long hours in the 48° F. sub-Antarctic waters, patching the larger holes outside with plywood and using leak-stoppers on the smaller ones. For the starboard crack, a special appeal was made to the people of Stanley for mattresses. Old foam and kapok mattresses were forced into the crack from keel to waterline, held in place with plywood. At the same time Leslie O'Neil was fixing massive steel plates nearly an inch thick to the top and 'tween decks above the crack for security during the flotation of the ship. Horst Kaulen, meanwhile, made ready to remove the masts. The pontoon was anchored stern on to the port side of the Great Britain, so that a crane erected on the pontoon could be effectively placed alongside each of the masts.

When she was wrecked the Great Britain had only three masts, but they were immense - those who saw the old ship beached in Sparrow Cove were probably more impressed by the masts and the enormous main yard than by the hulk itself. The main and fore masts, believed to be the largest sailing ship masts ever made, rose some 64 feet above deck level and sank 10 feet below. Fore and main masts weigh over 30 tons each and the yard, 106 feet long, is another 3 to 5 tons. The ship had to be relieved of this weight. The unknown factor was the condition of the wood, though Dr Corlett was certain that it was sound. To cut through the bridle and chains from which the yard was suspended, someone had to scale the 64 foot main mast, a job which in normal circumstances would only be done with scaffolding. Sergeant Tony (Yorky) Stott, of the Royal Marines, volunteered. Using only a climber's knots, he became the first man known to reach the top of a mast for a generation. Of the three masts, Horst Kaulen decided to remove the mizzen first. A local master carpenter, Willie Bowles used his chain saw to cut the mizzen below the level of the top deck; the mast was lifted on the crane about 15 feet but did not come free easily and eventually a rotten section in the lower end cracked and the mast broke crashing through the remains of the deck-house. It was then decided to cut the remaining masts above deck level. When the mainmast was cut, it was found to be in excellent condition and made up of four separate pitch pine trunks with 14 shaped pieces completing the exterior circle. This, together with the foremast, was secured to the pontoon to be taken back to Britain: the mizzen was left in the Falklands, where it will commemorate the years the Great Britain stayed in the colony. Then followed the most trying time of the salvage operation. Would the ship float? Was the pontoon in deep enough water for the hulk to pass over it? And would the weather be kind? Midnight on 6 April was the effective beginning of this phase. O'Neil and his divers started four pumps, with a total capacity of 660 tons of water an hour. The machines pounded through the night, pumping out more than 3,000 tons, and at 7 a.m. the Great Britain was clearly afloat - though just a few minutes too late to meet the early morning tide. So well did the ship float that after the gales and dramatic events later that afternoon, the Great Britain had again to be beached, which was just possible as a few holes hitherto undiscovered became obvious in the hulk during the pumping. For the next three days 35-knot winds and gusty storms made work nearly impossible, yet allowed no rest for fear that the old ship might again try to escape. On 10 April dawn was reasonably calm with some blue sky, and Horst Kaulen made his decision. Mulus III was already submerged and a Falkland Island Company tug, the Lively, was called out from Stanley. Together with the Malvinas, owned by Chris Bundes, who farms at Sparrow Cove, it towed the Great Britain towards the pontoon. Another and perhaps the most important problem then became apparent; the draught of the ship was greater than had been calculated. It was a technical difficulty which had been anticipated but which could only be faced at the time when the Great Britain was ready to float over the pontoon. The difficulties involved in assessing her draught were enormous, particularly as all calculations had been made when the masts, spar and water were still inside the ship. Dr Corlett had worked on a stern draught of 12 feet, but Horst Kaulen found it to be nearer 14 feet, plus an additional discrepancy from the 'hogging' of the keel. It was therefore necessary to manoeuvre the pontoon into deeper water. This was done by raising it and swinging it through 90º on the main anchor before sinking it again. The next day was a memorable one for everyone concerned. The weather was still far from settled but looked as if it might hold out for a few hours. The Great Britain, made fast to the front dolphins (tubular steel pillars) welded to the pontoon, was ready at high tide to be floated over Mulus III. With the aid of the Lively and Malvinas, the enormous hulk was towed forward, slipping snuggly between the 'dolphins', and all went well until within the final 25 feet, when for no clear reason she stopped. Even with the added power of Varius II at her stern, she would budge no further. Senior diver Don O'Hara later found that the keel had grounded slightly. During the day, thick mud accumulated during the years inside the ship was washed out and with a slightly higher evening tide the Great Britain was placed firmly over the pontoon by 8 p.m. That night, some time after midnight, the crew of the Varius were startled by a tremendous report; the new steel plates had done their job and were now buckling under the strain as the starboard crack closed up when the iron ship settled on the pontoon with the falling tide. All that remained was the tricky job of lifting the pontoon under the Great Britain, raising the rusting hulk some 10 feet out of the water. For stability, the fore end of the pontoon was raised first, 7 of the 15 compartments being pumped clear of water. Under Horst Kaulen's expert guidance, this was done by late in the afternoon; the date and time had a special significance as it was exactly 33 years to the hour that the Great Britain had been beached in Sparrow Cove. The day the ship was taken back to Stanley will be recorded in Falkland Islands history. Many of the older generation remembered the day she was towed away. The far western islands of Carcass and Westpoint reported on the weather throughout the morning, though from early hours the forecast looked unpromising. Gale force winds, gusting to 45 knots, were recorded in several places and appeared to be surrounding Stanley though not actually hitting the town. A snow blizzard struck in mid-morning and Port William, which lies between Sparrow Cove and Port Stanley, was rough. Captain Hertzog left Sparrow Cove with the Great Britain on Mulus III on the starboard side of Varius II with sister towing tugs Lively and Clio out front and the Malvinas at the stern. The rising wind and swell gave the flotilla a rough passage, but at midday Captain Hertzog skilfully negotiated the narrows which guard Stanley harbour, greeted by the siren of RMS Darwin and the bells of Christchurch Cathedral. Later, at a simple ceremony held beneath the massive bows, the Governor, Sir Cosmo Haskard officially transferred the Great Britain to the project committee. The jetty was crowded with onlookers as Miss Madge Biggs MBE returned the weatherglass which her shipwright grandfather had saved when the Great Britain arrived in 1887. It was a symbolic gesture made on behalf of the many islanders who, having looked after the Great Britain for so many years are now contributing relics kept for 83 years for the restoration of the 'Old Lady of the Falklands'. Now, as the old ship returned home to the Bristol dock in which she was built, she was making one more record. The 7,000 mile journey from the Falklands to Britain was expected to take between 50 and 60 days - the longest tow of its kind ever made. How and when the ship will be restored is not yet clear. Dr Corlett, who has studied and researched the ship in infinite detail, hopes to restore the exterior to Brunel's original 1843 design, including the six masts. Preservation and restoring the external features could be a comparatively short task, but the interior will take much longer. Projects include conference rooms and a replica of the Victorian furnishings. But now the major problem once again is finance. The Great Britain is probably the greatest ship ever built and she has a special significance for the British public. She is a landmark in marine history. But how much will the restoration cost and will the British public pay the price?

| ||||||||

|