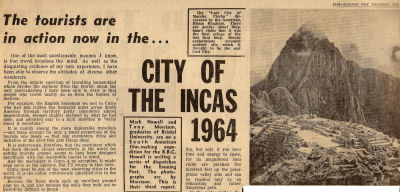

Bristol

Evening Post, Thursday, October 29 1964 Bristol

Evening Post, Thursday, October 29 1964

One

of the most questionable maxims I know, is that travel broadens the mind. As well

as the disquieting evidence of my own experience, I have been able to observe

the attitudes of diverse other wanderers. From

the infinite spectrum of travelling human-kind which divides the explorer from

the tourist, about the only generalisation I have been able to draw is that people

who travel mostly do so from the haziest of motives. For

example, the English horseman we met in Cuzco who had just ridden two thousand

miles across South America through territory justly considered almost impenetrable,

seemed slightly alarmed by what he had done, and admitted only to a mild ambition

to "write about it sometime." It

is mainly among the more deplorable travellers - and these account for only a

small proportion of the tourists one meets - that one encounters drive and initiative

of the kind that gets things done. It

is unfortunate, therefore, that the machinery which has been devised, almost everywhere

in the world for getting tourists around, seems to have been designed specifically

with the deplorable tourist in mind. And

the machinery in Cuzco is no exception. It might even serve as the epitome. But

I'll return to that later. One

of the World's most absorbing cities Cuzco

must be one of the most absorbing cities in the world. It is the oldest continuously

inhabited city in the Americas. Because the Incas made such an excellent ground

plan for it, and also because the walls they built are so incredibly difficult

to knock down, the centre of the modern city rests almost exclusively upon Inca

foundations and the streets and the alleyways are those they designed. Sitting

in a café, over your lomo montado, you are as likely to be enclosed

by Inca masonry as by hardboard or plaster, and not even the super-imposed Coca-Cola

signs can detract from its alien formidability. (Its tendency under these conditions

to inhibit the appetite can, and must be forgiven). Unmoved I

need hardly add that whenever there has been an earthquake in Cuzco it has been

necessary only to rebuild the upper, modern levels; the lower Inca walls have

remain unmoved. But

because it was the Incas capital, Cuzco is now inevitably the tourist centre of

Peru. Which is a pity, for the points of view of tourist and Inca are irreconcilable.

Whereas the tourist is essentially a hasty individual, the Inca, one conjectures,

must have been as solid and painstaking as his walls. He

was concerned only with precision, with massive masonic conformity with the rugged

Andes which surrounded him And

the tourist skipping across the mountains by air in forty minutes is as likely

to be assailed by mental indigestion, as by wonder, at the Stone Empire. Indifference There

is a tendency, too, for the Cuzquenos to be interested in their Incaic

forbears mainly as a tourist attraction, and the consequence is that Cuzco is

curiously patchy;- in appearance Kodachrome adverts and Inca walls; and in spirit

- priceless antiquity overlaid by conspicuous opportunism. In the shops one can

encounter bored indifference and it is not difficult to find rudeness. In

the streets one is pursued by children's cries of "money! money!",

the only English word many of them know; it's all part of the price paid for intensive

tourism. Even

less appetising is the spectacle of the tourists themselves, in action, but here

there often creeps in a compensating element of humour. Each

Sunday morning, very early, the Indian proprietors of the Cuzco market close down

their little stalls and adjourn to the village of Pisac in the nearby Urubamba

valley. All

through the week they have been offering their wares within a hundred yards of

the tourist hotel, though largely neglected by the visitors. Market Not

long after the Indians' departure, the tourists receive their carefully prearranged

early calls, gulp hasty breakfasts, and set off for Pisac in hot but unwitting

pursuit of them. For the Pisac market, with its Incaic associations, is an event

all are adjured not to miss. Last

Sunday, Tony and I joined some Indians, a few pigs, a box of chickens and a harp

in the back of a small truck and made our way across to Pisac with the first wave.

Pisac is well worth visiting, but only if you have time and energy to spare for

its magnificent Inca ruins are perched five hundred feet up the precipitous valley

side and can only be reached by an exhausting and rather dangerous path. In

the valley bottom the village square is half occupied by country Indians who come

in from remote villages to sell their wares to each other, and half by the contingent

that has made the trip from Cuzco. On one side are the lovely, subdued colours

of the country Indian homespun and dyed clothes, and on the other, the garish

aniline of the Cuzco traders. Dollars Presently

the tourists arrived and while Tony was taking pictures I strolled around to see

what was on sale. Interestingly, prices were quoted, and accepted, in dollars;

I heard no mention of Peruvian soles. The

prices were higher, of course, much higher than in Cuzco. Still, twenty miles,

in the Peruvian Andes, is twenty miles; not a journey lightly or cheaply to be

undertaken. I

watched for a while a thickset middle-aged American woman in luminous purple jeans

and a bilious sweater being charged double the priced I had been asked in Cuzco,

for a fine black and red poncho I had much admired there. Then the stout Indian

trader attending her, in a dumb show of great power, invited me over her shoulder

to make myself scarce. This,

it was no great effort to do. To anyone as reactionary-minded as myself, the hanging

ruins, the growing Urubamba, the all-pervading atmosphere of the great Indian

civilisation, did not afford a suitable context for Bermuda shorts, even less

for the transistor radio whose maniacal bleat eventually inevitably wandered on

to the scene. My

feeling, despite a couple of compensating horse-laughs, is that the ghosts of

Pisac should do something drastic about it.

|