The

Music of the Missions

| † | | † |

| | Today

you can fly there but 450 years ago a wilderness lay beyond the falls |

| In

this story we join music student Imogen Hares who in 1998 travelled to the heart

of South America to find the lost music of the 18th century Jesuit Missions of

the 'Green Hell' | An

Immense Land Parts

of this immense land are still unexplored. It's a world of scrub forest, huge

swamps and two of South America's greatest rivers, the Paraguay and the Parana.

Floods are common - on one occasion the water was so high that these falls virtually

disappeared. Huge trees were thrown about like toys. The spray could be seen from

miles away rising above the forest like a plume of white smoke and the roar was

deafening.

Here was the homeland of numerous tribes, some nomadic, or

simple fishermen, or hunters. On the way they collected honey, insect grubs and

a few wild berries. Not too long ago their ancestors used the shells of giant

armadillos for shelter. Today the land is shared by three countries Argentina,

Paraguay and Bolivia. The central part is known as the Chaco. The

Green Hell

The

first European to cross this Green Hell between the Atlantic and the Andes mountains

far to the west was a Portuguese sailor, Alejo García. He joined

a band of wandering Guaraní for the journey but never survived to tell

his story. He was murdered on the way back to the coast. Alejo García was

following a trail of silver known to the native Americans. They said it came from

distant mountains. The race to reach the silver treasures in the Andean

realm of the Inca/ Inka had started.

The route through the 'Green Hell' was terrible and as history tells it was Francisco

Pizarro from Trujillo in Extremedura, Spain who was the first to get the prize.

Pizarro reached the Andes from the Pacific side. Numerous

adventurers followed Alejo García and in 1661 a Spaniard, Ñuflo de Chávez reached the foot of the Andes and founded the city

of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, a name he gave after his home village in Extremadura,

Spain. The next three centuries saw little progress with the route. In fact

there was a political tension between the Spanish who had settled in the east

and those who controlled fabulous silver mines in the west. The native Americans

were hostile and The Green Hell remained something of a no-mans' land. The Spanish

authorities would have welcomed true settlement but it never happened. Just a

few fortified outposts were established around the Chaco and it was left to the

determined followers of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits to pentrate the wilderness

and 'pacify' the native Americans. The Jesuits were active throughout South America

but they are most remembered for their dedication to the remote lands of the Paraguay,

Parana Rivers and the Chaco. There they built an almost autonomous state, out

of reach of the Spanish goverment. One nucleus of Jesuit power was in Chiquitos

some 300kms northeast of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia.

Ñuflo de Chávez reached the foot of the Andes and founded the city

of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, a name he gave after his home village in Extremadura,

Spain. The next three centuries saw little progress with the route. In fact

there was a political tension between the Spanish who had settled in the east

and those who controlled fabulous silver mines in the west. The native Americans

were hostile and The Green Hell remained something of a no-mans' land. The Spanish

authorities would have welcomed true settlement but it never happened. Just a

few fortified outposts were established around the Chaco and it was left to the

determined followers of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits to pentrate the wilderness

and 'pacify' the native Americans. The Jesuits were active throughout South America

but they are most remembered for their dedication to the remote lands of the Paraguay,

Parana Rivers and the Chaco. There they built an almost autonomous state, out

of reach of the Spanish goverment. One nucleus of Jesuit power was in Chiquitos

some 300kms northeast of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia. |

| Santa

Cruz de la Sierra - Bolivia |

|

When

Bolivia gained independence from Spain in 1823, the lands granted to the young

Republic included the northwestern Chaco and Santa Cruz de la Sierra. The city

became the centre of a Department in 1826. For much of the 19th century

and well into the 21st Santa Cruz was isolated. | |

Whichever way they

chose it took a very hardy traveller to make the journey whether from the Andean

side or from Paraguay. To put this in perspective, the first hard-topped

road link to Cochabamba, the nearest Bolivian city was not completed until 1950.

Ten years later the streets of the city were still unpaved and deep in mud. The

best local transport was a horse, after that a wooden cart drawn by oxen, and

for a few - the 'Willys Jeep'. |  |

|

All

that has changed and Santa Cruz is now one of the fastest growing and prosperous

cities in South America. It is rich from the agricultural land that was once forest

and from natural resources such as oil, gas and iron ore. From a population of

60,000 just 45 years ago Santa Cruz is now home to over a million. |

| |

The

Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos |

|

Once

away from extensive level, open farmland that has brought prosperity to Santa

Cruz, roads to the east lead to undulating hills, covered with remnants of forest.

The name Chiquitos comes from Chiquito a local native American tribe. Imogen

Hares a music student travelled to the 17th century missions. One journey by bus

along a dirt road took 18 hours. In recent years the main roads have been paved.

In the 17th century Jesuit missions were built around a central courtyard. The

church occupied one side and the bell tower was separate.

|

| Mostly

the churches were wooden with clay tile roofing and over the years they

became derelict. In the late 1970's renovation work began and the Chiquitos

missions are now classed as a 'World Heritage Site'.

Of ten original missions in Chiquitos six have survived - San

Javier, Concepción (right), Santa Ana, San Rafael, San Miguel

and San José de Chiquitos | |

|

|

|

Restoration

of the missions at Concepción 1756 (above) and

at San Javier (1692), (left) the oldest of the six, were the work of Father Martin

Schmidt, a priest from the canton of Lucerne in Switzerland and German architect

Hans Roth. Part

of the Jesuit philosophy was to teach the native Americans crafts such as carving,

gilding and painting. The forest people were already skilled in many of these

including woodworking, painting body designs, making weapons and building

their homes. The Jesuits found willing pupils and introduced their European

styles and religious icons.

| By

the mid-18th century, the Jesuits were very successful with their teaching and

all powerful in this part of South America. The Spanish Crown was concerned by

their strength and in 1767 the Jesuits were expelled.

Apart from

a few local settlers who remained, the mission centres were abandoned. |

|

| | The

Music |

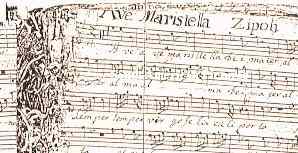

| The

priests discovered a latent talent for music among the native Americans. They

introduced European instruments including violins and harps which local craftsmen

copied. The missions soon possessed a repertoire of locally composed hymns and

other music and it was left behind when they were abandoned. Many sheets

somehow survived the tropical climate and the first were unearthed from piles

of old church documents in the 1980's. The work was begun by Gabriel Garrido an

Argentinian specialist in Baroque music |  |  |  |

| Part

of an original 17th century paper sheet of music used in the Missions of Chiquitos.

The work by Domenico Zipoli from Prato, close to Florence is part

of an extensive collection preserved by Bolivian specialists. This fragment

is from Ave Maria Stella a Vespers hymn sung on Feasts of the Blessed Virgin Mary |

|

| South

American Pictures and Imogen Hares [now Imogen Atkins] would like to thank Piotr

Nawrot SVD, the late Hans Roth and the office and the Director and staff of the

Festival Internaciónal de Musica Renacenista y Barroca Americana

'Misiones de Chiquitos' |

|

|

| The

text and most of the images are © Copyright |

| For

any commercial use please contact | | |

| THE

NONESUCH - FLOWER OF BRISTOL |

| AN

EMBLEM FOR ENTERPRISE | | |

|

|

|