Tony

Morrison writes  Colonel

TE Lawrence best known as 'Lawrence of Arabia' was one of the great names in Middle

Eastern politics, adventure and literature before the Second World War. In the

late 1950s the region was again in turmoil and the name Lawrence was revived by

a stage play, Ross, in 1960 at London's Haymarket Theatre. Lawrence was

a complex person and had assumed the name Ross in 1922 when he tried to disappear

from public view. He found a place in the Royal Air Force as Aircraftsman Ross. Colonel

TE Lawrence best known as 'Lawrence of Arabia' was one of the great names in Middle

Eastern politics, adventure and literature before the Second World War. In the

late 1950s the region was again in turmoil and the name Lawrence was revived by

a stage play, Ross, in 1960 at London's Haymarket Theatre. Lawrence was

a complex person and had assumed the name Ross in 1922 when he tried to disappear

from public view. He found a place in the Royal Air Force as Aircraftsman Ross.

Virtually

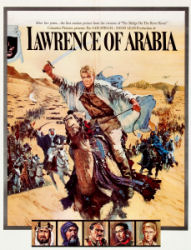

parallel with the stage production of Ross, David Lean the great British

film director drew on every element of Lawrence's life to create a blockbuster

production. Released in late 1962 Lawrence of Arabia was filmed with some locations

in Jordan. The film won seven Academy awards and was the highest grossing movie

of the era. Peter

O'Toole a young actor new to cinema was given the lead and later won a Golden

Globe for his portrayal of Lawrence. I met O'Toole at a Bristol Old Vic theatre

party when I was at university in Bristol. Did I say 'plastered'?….. Peter

who at the time was the lead in many of the productions at the Theatre Royal including

William Shakespeare's Othello, held court lounging on a sofa in a student's dingy

flat in Clifton, now an upmarket part of the city, but beyond that image my memory

is hazy. In

the footsteps

Then

early in 1962 I caught up with O'Toole or at least his footsteps and a litter

of empty Scotch boxes beside an Army fort in the Jordanian desert. I was part

of a small team of four making Adventure films for BBC television. In front

of the camera we had Tom Stobart who filmed the 1953 Conquest of Everest

and Ralph Izzard who had spent his life as a correspondent with the London Daily

Mail. Ralph was our ' in house fixer' as he had lived in Beirut with his wife

Molly in the 1950s and had contacts across the Arab world. The sound recordist

and second camera was Michael Gore. I remember 'Mike' well as he was slightly

younger than me and supremely sharp witted. The

Pilgrims' Railway  The

theme of our film was 'Lawrence' and the defunct Hijaz Railway - sometimes known

as the Pilgrims' Railway. Tom said someone had mentioned ' that there

were rumours that the wreck of a train Lawrence of Arabia had blown up near Mudawarrah

in 1918 on the Saudi Arabian border was still to be seen lying scattered in the

dust……' We were told that we could find bits of military hardware

that had not been touched so it was a ready-made BBC Adventure film story. The

theme of our film was 'Lawrence' and the defunct Hijaz Railway - sometimes known

as the Pilgrims' Railway. Tom said someone had mentioned ' that there

were rumours that the wreck of a train Lawrence of Arabia had blown up near Mudawarrah

in 1918 on the Saudi Arabian border was still to be seen lying scattered in the

dust……' We were told that we could find bits of military hardware

that had not been touched so it was a ready-made BBC Adventure film story.

In Lawrence's

time the Ottoman Empire dating from the 15th century and with even older roots

was in decline but the Turks still influenced much of the western side of the

Arabian Peninsula, now largely Saudi Arabia. The Turkish subjection of the region

with military backing from Germany and with expansionist ideas was clear even

though oil had not yet been discovered there. The only known oil deposits were

of shale oil in the Yarmouk area, now in the north of Jordan close to the Syrian

border. Lawrence

was a British Army officer working with the tribes of the Sinai (now part of Egypt)

and Palestine (larger at the time) against the Ottoman Turks and their German

supporters. Lawrence had plenty of experience as before joining the Army he had

worked on archaeological sites and mapping along the northern border of Syria.

He enjoyed the life and gained a rapport with the people. The

Arabian Peninsular was a sparsely populated wilderness of roughly 3 million sq.

kms and only wandering tribes knew the way between water holes and the few large

oases. It was not a place for the foreigner and outsiders were not welcome. Among

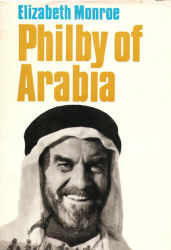

the most detailed early records of the interior are those of St. John Philby,

the curiously eccentric father of the master spy, Kim Philby. The best short reference

is the aptly titled and scholarly book by the late Elizabeth Monroe. St.John

Philby  St.

John Philby was a civil servant and fluent linguist, having studied modern languages

at Trinity College, Cambridge followed by another year studying Indian and Oriental

languages with a scholarship from the Indian Civil Service. He was sent from British

India to work in Basrah, Mesopotamia - now in Iraq. The Turks had been driven

out by British forces sent from India and St.John was working to help restore

order. St.

John Philby was a civil servant and fluent linguist, having studied modern languages

at Trinity College, Cambridge followed by another year studying Indian and Oriental

languages with a scholarship from the Indian Civil Service. He was sent from British

India to work in Basrah, Mesopotamia - now in Iraq. The Turks had been driven

out by British forces sent from India and St.John was working to help restore

order.

By this time in the war the British Government was looking for a way to bring

together the many Arab tribes as a united front against the Ottoman Turks, and

St.John Philby was dispatched to the middle of the Arabian Peninsula to meet Abd

al-Aziz ibn Saud, ruler of an area known as the Najd and allied with the Wahibi,

a sect of fundamentalist Muslims. The

journey St.John Philby made across the peninsula took him 44 days. Only one European

had made the crossing before him, almost 100 years earlier, in 1819, and he was

Captain Forster Sadlier of the 47th Regiment. Sent by the Government to congratulate

an Egyptian commander for his success against the Wahabis …. 'he marched

1200 miles, in European dress across every natural obstacle from Ka-tif to Yam-bu….'.

An amazing sight…. and an amazing feat. For

this journey in 1917 and another in 1918 St.John Philby was honoured in 1922 with

the Founders' Medal of the Royal Geographical Society, London, a gold medal authorised

by King George V. The

Hijaz  Bordering

the Red Sea the western edge of the desert peninsula is a region of about a 25,000

sq kms known as the Hijaz which was and is immensely important. The two most revered

cities of the Islamic world, Medina and Mecca, are found there. Bordering

the Red Sea the western edge of the desert peninsula is a region of about a 25,000

sq kms known as the Hijaz which was and is immensely important. The two most revered

cities of the Islamic world, Medina and Mecca, are found there.

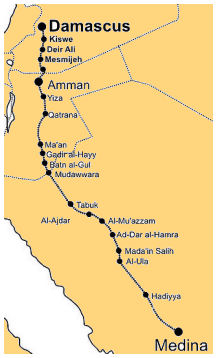

The

Hijaz Railway from Damascus, Syria, then part of the Ottoman Empire to Medina,

some 1319 kms, was first suggested in the 19th century to replace the existing

Pilgrims' camel route through the pitiless desert. Thousands of muslims from the

Ottoman Empire made the annual hajj to Mecca along a trail with fifty-two

stops, each with a stone water cistern or well. As the camel caravans made the

way slowly the hardships were felt by some as part of the pilgrimage. Although

built largely with the aim of carrying the pilgrims, another rationale for the

line and obvious benefit for the Turks, was economic and territorial expansion.

The Hijaz Railway became a strategic supply route in the desert war and an obvious

target for Lawrence and his loosely linked tribal guerrilla force. The

Hijaz line started in Damascus where the already existing Ottoman railway running

south from Constantinople (Istanbul) on the Bosphorus - the narrow strait between

Europe and Asia - terminated. With German engineers advising, the construction

of the Hijaz Railway began in 1900 under the auspices of the Ottoman Sultan Hamid

II. A stamp tax willingly paid by the pilgrims funded the construction and by

1908 the line had reached Medina. A spur line led to Haifa on the Mediterranean

coast and opened the Yarmouk shale for German exploitation. Some of the oil was

used to fuel railway locomotives. Our

route southward We

had two Land Rovers and our route lay southward from the Jordanian capital, Amman.

Our first stop was Ma'an 195kms and once an important stop on the Hijaz line.

Beyond Ma'an the road deteriorated and the desert closed in. Colonel

F.R Maunsell, a Military Attaché in Constantinople who travelled on the

railway when it opened, wrote...

'the line enters a spirit world without towns or even inhabitants. The stages

south of Ma'an were the most desolate of all and the way was strewn with dead

or dying camels'. We

arrived at a fort in Wadi Rum  By

the time my camera rolled on Take One of my second professional television film,

the massively expensive unit shooting 'Lawrence' had moved on and the movie was

in the cutting room. Like the huge 'Lawrence' team we had the backing of King

Hussein of Jordan who provided the support of the Army's long-range Desert Patrol

- the Royal Jordanian Desert Force. This was a camel-borne elite group of Bedouin

who covered the desert end-to-end. By

the time my camera rolled on Take One of my second professional television film,

the massively expensive unit shooting 'Lawrence' had moved on and the movie was

in the cutting room. Like the huge 'Lawrence' team we had the backing of King

Hussein of Jordan who provided the support of the Army's long-range Desert Patrol

- the Royal Jordanian Desert Force. This was a camel-borne elite group of Bedouin

who covered the desert end-to-end.

Also like the Lawrence of Arabia unit we were to be based at the Desert Patrol

fort in the spectacular Wadi Rum, a land of eroded sandstone rising to 1,700m

above the desert. The

Bedouin tents for the men and their families were det up outside the compound.

Camels for daily use were kept inside and the road leading out was no more than

a dirt track that was passable in all but the worst rain. We were there in Spring

so the desert was tinged green with wonderful array of plants. But

after that, any similarity with the David Lean production ended and we faced a

remarkable journey through empty desert into the Arabian Peninsula. The asphalt

roads and land irrigated from bore-holes seen there today simply did not exist.

We continued

in our Land Rovers for a further 68kms by a clearly marked desert trail to Wadi

Rum - now a popular tourist destination. At a small Army fort in the wadi we met

the Desert Patrol who had been warned of our arrival by R/T wireless and one of

the officers guided us another 66kms through a pure arid wilderness. In

places the trail led through more eroded hills and sometimes across perfectly

flat dried mud where in rain it would have been impassable. Our final destination

was Mudawarrah then little more than a ruined Hijaz Railway station where we met

some Bedouin, the wanderers of the desert in their tents of woven goat hair. Bedouin

hospitality  We

were welcomed royally with a mensaf a traditional dish for honoured guests,

A hand-beaten brass plate about a metre across with a shallow depression in the

centre for the food, was brought to the tent side by the Bedouin women who remained

out of sight. The men seated us on the ground with the plate on a hand woven kilim

and offered roasted lamb and a rice, with I recall had a slightly acrid flavour,

possibly from some rancid butter - samneh. Don't ask about the traditional

sheep's eyeball - luckily Tom was accustomed to the treat and scoffed it with

thanks… in Arabic. We had coffee scented with cardamum and for an hour or

more we talked with our Desert Patrol guide as interpreter. We

were welcomed royally with a mensaf a traditional dish for honoured guests,

A hand-beaten brass plate about a metre across with a shallow depression in the

centre for the food, was brought to the tent side by the Bedouin women who remained

out of sight. The men seated us on the ground with the plate on a hand woven kilim

and offered roasted lamb and a rice, with I recall had a slightly acrid flavour,

possibly from some rancid butter - samneh. Don't ask about the traditional

sheep's eyeball - luckily Tom was accustomed to the treat and scoffed it with

thanks… in Arabic. We had coffee scented with cardamum and for an hour or

more we talked with our Desert Patrol guide as interpreter.

The

children were inquisitive and played with the camera. I recall how Mike let them

hear a play-back through headphones from his small recorder. The 'ice' if any

was broken and when we heard about the wrecked line we asked to see the place

and where train wreckage had lain twisted for almost half a century. Lawrence

and his tribal guerrillas had used explosives and wrecked the train. Sand

wisped over the rails......  Sand

wisped over the rails and putting an ear to the metal I was sure I could hear

the clickety-clack of wheels. 'That's fantastic' said Mike and he found

a packet of cigarettes in his typically British tweed jacket. He

hailed our Bedouin helpers. Within seconds Mike had sand billowing over the line

like a miniature dust storm. Sand

wisped over the rails and putting an ear to the metal I was sure I could hear

the clickety-clack of wheels. 'That's fantastic' said Mike and he found

a packet of cigarettes in his typically British tweed jacket. He

hailed our Bedouin helpers. Within seconds Mike had sand billowing over the line

like a miniature dust storm.

We

ran some film. It was the end of the story. More

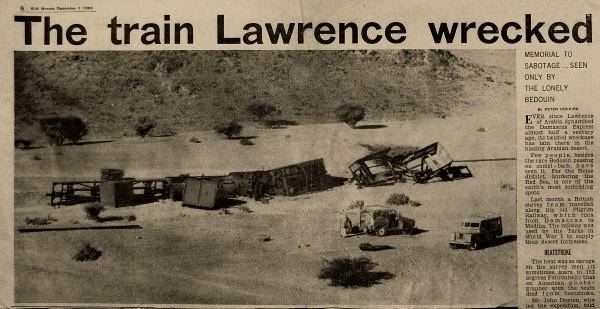

wreckage across the border The

wandering Bedouin told us that more wreckage lay in places further south including

entire locomotives, but the Saudi Arabian frontier was only another 15kms away

so Mudawarrah was our limit. But the story of the Hijaz Railway continued to flow

into our Nonesuch files for some years after the BBC filming. In 1964 The Hedjaz

Construction Company Ltd, based in London headed a plan to rebuild sections of

the line and Press coverage ran for some months.  Peter

Hopkirk Peter

Hopkirk

Peter

Hopkirk a journalist and author who went on to specialise in Middle Eastern and

Central Asian stories wrote a piece for the London Sun newspaper in December 1964.

He described a survey team working along the line - 'the desert heat was so

intense a photographer died of heat stroke - he just sank suddenly to his knees

-dead.' They found wrecked engines and bridges and 'They stumbled upon

a British Army fused gun-cotton pack left by the saboteurs 47 years ago.'

(gun-cotton = an explosive propellant used in artillery shells). The

Hijaz Railway was rebuilt in some sections but not for the entire length. Some

of the old locomotives were restored to working order and others are in museums.

Parts still lie in the desert. l. But

a final thought. When we were there in 1962 we heard that the broken line we saw

in Mudawarrah may have been wrecked, not by Lawrence, but by Major Robin Buxton,

a military commander in the Imperial Camel Corps and friend of Lawrence. I have

a note in my diary and apparently it could be true. Our

film narrated by Tom kept to the Lawrence tale and received some glowing comments

- 'the ceremonial hospitality of a Bedouin camp' 'a finely photographed piece'

' there's nothing like a camel train in semi-silhouette to stir the imagination.'

As journalists say 'Don't let the facts get in the way….' Epilogue Changes

- Mudawarrah is still there with numerous green patches for agriculture irrigated

from bore holes. The Bedouin have settled to tend the crops. A road runs south

to a customs post at the Saudi Arabian frontier. The old railway track has gone

leaving just the firm bed on which it ran. Most

recently

in 2012, some remains left by Lawrence and his Arab guerrilas have been investigated

by a team from the University of Bristol. The research project led by Professor

Nicholas Saunders has been named GARP - the Great Arab Revolt Project and has

been widely covered in the British Press and specialist magazines. It seems that

the Lawrence story is alive and well. T

E Lawrence

died from injuries received in a motor-cycle accident in England in 1935. His

name will be linked forever with the Arab Revolt of 1916 - 1918 by academics and

politicians. And, Lawrence's name will be remembered by many people thanks to

the David Lean film. Lawrence received military honours for his desert exploits

and the award of the Companion of the Order of the Bath, a British Order of Chivalry

dating back to 1735. Apparently he refused a Knighthood. Seven

Pillars of Wisdom is a mammoth book Lawrence wrote about his experiences and

has become a classic of the era. Various editions are known and some are rarely

seen. Revolt in the Desert is a shorter, popular edition of his work. St.

John Philby

died in 1960 and is buried in the Muslim cemetery in Beirut. He had converted

to Islam, His name and achievements tend to be overlooked because of his background

and opinions - also not to be forgotten is the legacy of his son Kim. The Times

of London published a long obituary with a photograph but failed to mention his

Royal Geographical Society award, his only official recognition in Britain. The

Empty Quarter

- more epic journeys The Rub' al Khali, also known

as the Empty Quarter, in the southeast of the Arabian Peninsular is the most arid

part and regarded as the world's largest unbroken desert. The first recorded journeys

there were in 1931 by Bertram Thomas a British Civil Servant, and in 1932 by St.John

Philby. Wilfred Thesiger whose name in the public mind is most often linked to

the Empty Quarter arrived more than ten years later to be welcomed by St. John

Philby.

St.John's story is told in his many books. A large number of his private papers

are kept in the Middle East archives of St. Antony's College, Oxford, England

Peter

O'Toole

died in 2013 with many film and stage awards. He wrote two books and his life

story is covered by literally hundreds of Press stories and reviews Peter

Hopkirk died in 2014. He had written six books, of which, perhaps,

The Great Game -1992 was best known - it covered the struggle for Empire

in Central Asia. In 1992 Peter was awarded the Sir Percy Sykes Memorial Medal

by the Royal Society for Asian Affairs.

|