This

is a story of Cheddar Man from the discovery of the skeleton in 1903 to my photography

in 1957........ and incredibly it will not mention DNA, brown skin and blue eyes

except in a Footnote. This

is a story of Cheddar Man from the discovery of the skeleton in 1903 to my photography

in 1957........ and incredibly it will not mention DNA, brown skin and blue eyes

except in a Footnote.

Reason

- Back in 1957 DNA sequencing was not much more than a science dream as the groundbreaking

discoveries of Francis Crick and James Watson in Cambridge were new. Ther

idea of the double helix was literally hot off the academic Press in the journal

Nature of April 1953 with a paper........Molecular Structure of Nucleic

Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid....... OK OK ...so if you

want the skull pictures scroll to the bottom. If you do you'll miss the story.

I

have added some web references - not as links but in keywords [KW]

in your search engine as

I feel links spoil the flow. While some of the KW references

may look academic others are good reads and packed with chuckles - list the

KWs as you scroll and enjoy later.

My

starting point

Thinking

of my time at the University of Bristol I can see it was split very unevenly between

zoology, my chosen study, photography which simply went into overdrive and the

Spelaeological Society - the UBSS - known to most students as the Caving Society.

The

Mendip Hills

Black

Down Mendip Hills 1957- Autumnal bracken covers the high places Bristol

could not have been better located for caving. The Mendip hills or more loosely

just 'the Mendips' is a wonderful span of carboniferous limestone about twenty

kilometres south of the city and ranges east to west for over thirty kilometres.

The limestone is largely calcium carbonate formed from the skeletons of minute

animals 363 to 325 million years ago. For caving, the sheer adventure of climbing

wire ladders in the dark, slithering through muddy tunnels just big enough for

a large mole or diving in bottomless pools - all a bit exaggerated you will guess....us

cavers had it made.

The Mendips have been classified as an AONB [Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty]

since 1972 and with obvious reason. On the northern flanks the wooded 'combe'

[deep valley] at Burrington is exceptionally beautiful and seems untouched even

though a road passes through its length. Then from Burrington the hills rise steeply

southward and bracken covered over Black Down, the highest point at 323 metres.

In the 1950s

our course-work included collecting and identifying insects and other invertebrates

in Velvet Bottom Gruffy

- Anna Verrinder

and Elizabeth Pleass On

the southern side of the Mendips the land is farmed apart from small areas such

as the GB [Goddard and Baker] Gruffy Nature Reserve, approximately seven

hectares owned by the Somerset Wildlife Trust. In 'Mendipese' Gruffy refers to

a place dug up long ago for minerals such as lead ore, leaving holes and uneven

ground. The entrances to two major caves, GB and Charterhouse lie within the boundary

of the GB Gruffy. Two Bristol cavers FG Goddard and CC Baker discovered the cave

in 1939. But these

caves are for experienced cavers only and water flowing into them follows a course

downhill to emerge about 160 metres lower and two kilometres away in the impressive

Cheddar Gorge, one of Britain's Natural Wonders. The river, known as the Cheddar

Yeo, is Britain's largest underground river - we will meet it again when we get

to the Cheddar Caves. Most

of the rain falling on the southern side of the Mendips enters fissures /swallets

in the limestone and flows underground to 'risings' such as in Cheddar Gorge or

in Wookey Hole, a fabulous cave a few kilometres to the east, noted for its River

Axe with underground pools.  On

the right two cavers are in Swildon's hole one of the caves feeding water

to Wookey Hole ( Dr. Oliver Lloyd and Dr. Don Thompson) On

the right two cavers are in Swildon's hole one of the caves feeding water

to Wookey Hole ( Dr. Oliver Lloyd and Dr. Don Thompson)

Over

to the west of the Mendips there's Brean Down with its Romano-British temple overlooking

the Bristol Channel...... You can see I'm sold on the place and before I left

Bristol I had been through many of the caves and even had the dubious honour with

two cavers, both medical doctors, of setting light to Wookey Hole… maybe

worth a footnote? 1955

and I joined the Caving society Here

at the 'Freshers Squash ' Andrée Rosenfeld (left), Sheila Watkins and Struan

Robertson with a human femur or two hanging from the ceiling - perhaps not a PC

introduction today. A metal runged caving ladder and a miners helmet decorated

the stand.

The

Mendips offered me the best of caving, walking and of course, many rural 'pubs'

such as the now lost Miner's Arms near Priddy for relaxation. It was late

in 1955 at the University Union 'Fresher's Squash' when I signed up for the 'Caving

Society'.

I soon

found the Spelaeological Society [UBSS] - a treasure trove of cave science. Burrington

Combe and Aveline's Hole  The

official founding of the Society goes back to March 1919 at a meeting of students

and staff attending a talk by a student, Lionel Palmer. The topic was Aveline's

Hole in Burrington Combe and its palaeolithic human remains. [Wiki] The

official founding of the Society goes back to March 1919 at a meeting of students

and staff attending a talk by a student, Lionel Palmer. The topic was Aveline's

Hole in Burrington Combe and its palaeolithic human remains. [Wiki]

Leo

Palmer was one of several students, who digging as the Bristol Spelaological Research

Society had excavated at Aveline's before the First World War. The numerous bones

they found had been hidden during the war years and were only recovered later

after pressure was put on one of the BSRS members.

Effectively

the bones were the property of the landowner George Wills of the enormously wealthy

and philanthropic Bristol tobacco dynasty.  Palmer

who to generations of UBBS members was known as 'Leo' went on to become Professor

of Physics at Hull University. Palmer was not the only guiding light and Edgar

Tratman - known as 'Tratty' was the first Secretary and went on to become a Professor

of Dentistry. To say the two 'cut their teeth' academically with the skeletal

finds at Aveline's hole is pushing my luck except it's true. Palmer

who to generations of UBBS members was known as 'Leo' went on to become Professor

of Physics at Hull University. Palmer was not the only guiding light and Edgar

Tratman - known as 'Tratty' was the first Secretary and went on to become a Professor

of Dentistry. To say the two 'cut their teeth' academically with the skeletal

finds at Aveline's hole is pushing my luck except it's true.

Right

Leo Palmer at a UBSS Christmas reunion - Picture by Gary Witts Far

from stopping further excavation George Wills insisted that it should be done

scientifically with the backing of the University so a new society, the UBSS,

was founded. And to this day the UBSS is the keyholder to Aveline's Hole. More

importantly the UBSS publishes a properly peer scrutinised and hence highly respected

journal The Proceedings. UBSS open science policy states The Proceedings

are freely available on the web and so easily downloaded as PDFs - meaning

for the history of the Society you can KW - UBSS History Shaw.

Trevor Shaw is a UBSS member and authority on cave history. Many

of the Mendip caves were once home to early man and animals. Bones, human and

from the ancient fauna, worked flints, pottery, ash and many rich details were

there to be uncovered. The UBSS Proceedings provide the written record

and many of the collected objects are kept in the UBSS museum at the University.

Aveline's

Hole is small, about sixty-eight metres long. But here right at the edge of a

road it is now recognised as Britain's oldest known cemetery. Aveline's has been

known since the eighteenth century when or so the local lore insists, it was discovered

by two men digging for a rabbit. Over the years accounts of the number of skeletons

have varied from upwards of 'two hundred'- more likely about seventy and the 'finds'

are now scattered. In

pre WWll 'digs' the UBSS removed many bones including fragments from twenty individuals

and one obviously 'ceremonial' from an age roughly contemporary with Cheddar Man

or about 9000 BP.

The UBSS 'finds' were taken to the Society museum in the

university but were lost with many other records in a 1940 WWll German bombing

raid. Today the UBSS has a catalogue of some of the surviving examples in it's

collection. KW- UBSS Aveline's

Hole remains or another report UBSS Aveline's Carbon

dating.

Wells Museum in Somerset in the city of Wells close to the

southern edge of the Mendips has more finds from Aveline's and it has to be noted

that Leo Palmer on his retirement from physics took up the post as Honorary Curator. All

this may seem a long way to get to Cheddar but if you have kept with me so far

do not despair. This is not an academic paper so here I will introduce three 'greats'

of UBSS caving from my era and before. Three

of Caving's 'Greats'  I

shot this picture over sixty years ago in mid-1957 at the Burrington Hut - the

Society's field HQ. I

shot this picture over sixty years ago in mid-1957 at the Burrington Hut - the

Society's field HQ.

My

camera was a small German built Kodak Retinette 'folding camera' and the film

was Ferraniacolor, an Italian film I processed by hand. The colour has been 'restored'

using software.

On

the left with the rope is the UBSS President, Professor Edgar Tratman always

known as 'Tratty' - he was the Hon. Secretary in the founding days of the Society.

'Tratty' died in 1978.

In

the centre is Lt.Cdr Trevor Shaw, now Dr.T.R Shaw OBE and recognised for his

more than two hundred papers and books mostly on cave history - always 'Trevor'.

[In 2018 he was 90]. On

the right is Dr.Oliver Lloyd a pathologist, an authority on melanomas - always

'Oliver'. Oliver died in 1985 and his contribution to caving in the Mendips and

Ireland was enormous - wait for the memorial story when we get to the home of

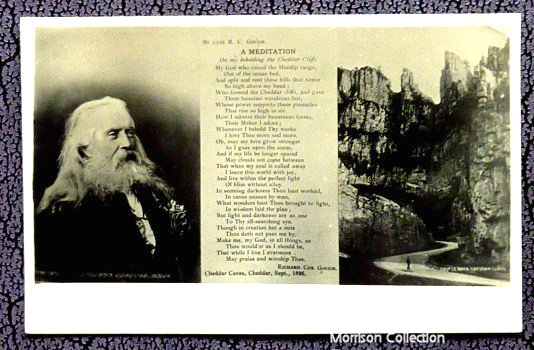

Cheddar Man. Richard

Cox Gough  Next

on the list is Richard Cox Gough whose name goes hand in hand with Cheddar Man

as the skeleton was found in one of his caves in Cheddar. Gough was born in Bedminster

a suburb of Bristol in 1826 at a time when the area was beginning to flourish

with small industries. His father was James Gough a man of property in Bristol

and his mother Lydia Cox was from Cheddar. Next

on the list is Richard Cox Gough whose name goes hand in hand with Cheddar Man

as the skeleton was found in one of his caves in Cheddar. Gough was born in Bedminster

a suburb of Bristol in 1826 at a time when the area was beginning to flourish

with small industries. His father was James Gough a man of property in Bristol

and his mother Lydia Cox was from Cheddar.

Richard

Cox Gough married a Welsh woman Frances Powell in Glamorgan in 1858 and moved

to Yatton on a major railway line southwest of Bristol. According to local history

he worked as the railway timekeeper on the Bristol and Exeter Railway, one of

the projects of the famous engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

At

that time the railway running south from Bristol had a branch line starting in

Yatton and running eastwards along the southern foot of the Mendips. The line

was extended to Cheddar and reached there in 1869. Maybe it was his mother's family

connection that led Gough to settle in Cheddar or he may have seen her cousin's

success with Cox's Cavern. Whichever….. we may not know but he stayed.

By

the time Gough settled in Cheddar sometime in 1868 the spectacular gorge was already

on the sightseers' route and several small caves were 'open' for short trips underground.

Top of the list was Cox's Stalactite Cavern by local tradition discovered in 1837

by George Cox a miller and Lydia's uncle. When George died in 1868 the lease of

the Stalactite Cavern passed to his son Edward Cox - Lydia's cousin. By

the time Gough settled in Cheddar sometime in 1868 the spectacular gorge was already

on the sightseers' route and several small caves were 'open' for short trips underground.

Top of the list was Cox's Stalactite Cavern by local tradition discovered in 1837

by George Cox a miller and Lydia's uncle. When George died in 1868 the lease of

the Stalactite Cavern passed to his son Edward Cox - Lydia's cousin.

Richard

Gough had an eye for getting some of the cave business as visitors to Cox's cave

were paying 'two shilings per head or a shilling each if more than three in a

party'. KW UBSS Cox's cave history

Irwin. Even non-commercial villagers who were living roughly in the

cave entrances or in modest cottages charged visitors a few pence for a visit

- I bet they did the old trick of blowing out the candle once out of sight of

daylight.

As

the crowds grew Gough sought to create a better cave than Cox's and by 1877 he

had opened his first, known today by cave historians as Gough's Old Cave. For

a magnificent story filled with the tittle tattle of the time KW

UBSS Gough's old cave Irwin As

the crowds grew Gough sought to create a better cave than Cox's and by 1877 he

had opened his first, known today by cave historians as Gough's Old Cave. For

a magnificent story filled with the tittle tattle of the time KW

UBSS Gough's old cave Irwin

Gough

made the cave pay but to make it bigger and better, he enlarged it with more stalactites

and stalagmites, some brought from other caves, and some very beautiful. These

formations are created by deposits of calcium carbonate left as the cave water

evaporates. The

source of the carbonate is the original limestone rock and as water passes over

the surface minute quantities of calcium carbonate are dissolved. If the water

is acidic due to carbon dioxide in the air or from rotting vegetation then more

calcium carbonate dissolves forming a 'bicarbonate' solution. When

the solution evaporates as it trickles over a surface such as the 'flow' in this

picture the process is reversed and calcium carbonate is deposited. As

a general rule stalactites are those formations growing downwards sometimes streaming

on a rock surface. Stalagmites are those formed on the ground by drips from above

and often they grow upwards. Sometimes the carbonate is deposited as a flow maybe

even a 'floor'.

Cave

rivals - an 19th Century family feud and a story of greed As

the nineteenth century moved on the rivalry between Gough's cave and Cox's intensified,

often bitterly, with each side purveying ever dodgier statements. It was Money

- money - money… money and every day counted. In

1877 Richard Gough began serious expansion by digging or blasting his way past

rocky obstacles to create wider openings, and by 1883 he had a show cave lit by

gas. Before the end of the 1880s Gough's New Great Stalactite Cavern

was making good money; more passages were discovered with splendid chambers complete

with fine stalactites and stalagmites. Electric light was installed in 1889 with

reflectors casting light on the glistening natural wonders. Richard Gough now

had the finest show cave in Cheddar and arguably in Britain. The

Great Leap Forward  A

great leap forward in Gough's fortunes came in 1892 when slightly lower in the

Gorge he was searching for a new entrance and he broke into a large cave system.

This is the Gough's Cave of today, known to cave historians as Gough's New Cave.

But the cave suffered

a problem as it held an underground river - the Cheddar Yeo. A

great leap forward in Gough's fortunes came in 1892 when slightly lower in the

Gorge he was searching for a new entrance and he broke into a large cave system.

This is the Gough's Cave of today, known to cave historians as Gough's New Cave.

But the cave suffered

a problem as it held an underground river - the Cheddar Yeo.

Gough

limited access to the river section and simply kept his New Cave to a system of

dry passages stretching to one side of the river and higher. Even so, when it

rained heavily up there on Black Down the water trickled, or sometimes rushed

downhill underground and closed the show cave. So drainage was vital and it could

be said that Cheddar Man was the Golden Goose born of a family feud and floods.

KW UBSS Gough's cave discovery development Irwin

The

discovery of Cheddar Man

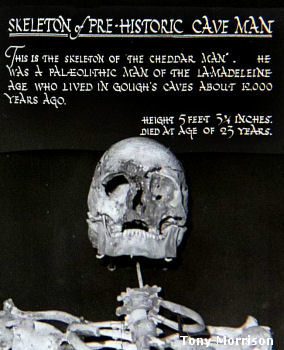

Richard

Gough died in 1902 and his New Cave passed to his widow and eldest son Arthur

to manage. The new team decided to tackle the water problem and within a year

Arthur and his brother William were digging a drainage channel close to the entrance.

Cave work was

usually undertaken in the low season and in December 1903 the brothers found some

human remains under an approximate thirteen centimetres layer of stalagmite in

a fissure. The stalagmite was not crystalline hard and the simplest description

is it was chalky soft with very thin layers mixed with sand - some hard, some

soft. Water laden with calcium carbonate had flowed across the sediments and gradually

a layer of calcium carbonate had been laid down. The

first bones the brothers noticed were pieces of a skull and being under the crumbly

stalagmite which would have taken centuries to form they knew they were old. Very

carefully the skull was taken out in pieces, more bones were removed -an arm,

a leg, some ribs and part of the pelvic girdle were laid to one side. But then

Arthur called a halt and sought professional advice. .jpg) .Three

names are recorded. Seventy-one year old Oxford educated Thomas Jex-Blake,

the Dean and Head of Chapter at the cathedral in the medieval city of Wells. .Three

names are recorded. Seventy-one year old Oxford educated Thomas Jex-Blake,

the Dean and Head of Chapter at the cathedral in the medieval city of Wells.

Right

The West Front of Wells cathedral. The Chapter House is just out of shot on

the left

Next on the list was Harold St George Gray an experienced archaeologist

who at thirty-one was Assistant Secretary, Curator and Librarian for the Somerset

Archaeological and Natural History Society in the county town of Taunton,

about twenty-five kilometres away across the often flooded Somerset Levels. And

Henry Nathanial Davies who at fifty-four was a local highly respected geologist

and Fellow of the Geological Society of London. St. George Gray later made a special

place in local history for his work on the ancient Lake villages on the Somerset

Levels. St.George

Gray noted his visit as 23rd January 1904 and commented on the skull. He wrote

'the skull was in many fragments, and in a condition that rendered very few

measurements or observations possible'. But at the same time he recorded how

he was discussing with the Goughs a possible home for the skeleton in Taunton.

St George Gray was published in Notes and Queries for Somerset and Dorset Volume

9 1905 which I found had been archived digitally by Stanford University in

the USA and was available online ….Oh our technology age …..Cheddar

Man must be rolling.

But

first on the early publishing scene was Davies who wrote an account read as a

'paper' at the Geological Society of London on April 13th 1904 and which appears

to be the earliest scientific report. But

first on the early publishing scene was Davies who wrote an account read as a

'paper' at the Geological Society of London on April 13th 1904 and which appears

to be the earliest scientific report.

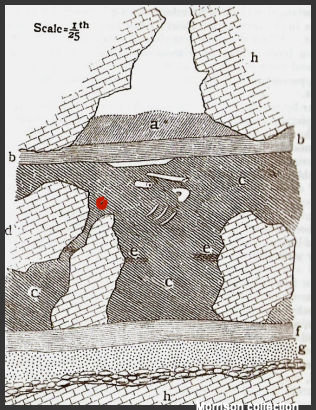

As

a geologist Davies noted two stalagmite layers - the chalky soft layer above (

b ) and a hard semi-crystalline layer below ( f ). The Layer ( g ) is of pebbles

and sand.

The

skeleton was in reddish earth / sand sediment between the stalagmite layers and

Davies drew a profile with notes about the position of the bones. I have added

a red dot for the skull. A

replica skeleton now part of the display in Gough's Cave is set in a position

based on an original description by Henry Davies where he suggested that Cheddar

Man could have drowned. That's unlikey say the specialists.

In

1904 photography was still young and analogue  As

far as I can discover these are the earliest published photographs of the skull

and I attribute one to H.N Davies and the other to Harold St.George Gray. It is

obvious that the skull was crudely reassembled shortly after discovery. As

far as I can discover these are the earliest published photographs of the skull

and I attribute one to H.N Davies and the other to Harold St.George Gray. It is

obvious that the skull was crudely reassembled shortly after discovery.

Davies

said 'the face is much mutilated and filled with a concrete of cave earth and

calcareous cement' .

l

Since

those early years the discovery of the skeleton has drawn wild estimates for its

age. One Gough's Cave booklet of the 1920s said the Prehistoric Man on view was

40,000-80,000 years old, and that was twenty years after the Goughs had published

a postcard with some estimates from St. George Gray saying the man was a cave

dweller who lived between the Palaeolithic and Neolithic ages. [Today Mesolithic

is described with a time span in Europe of 11,600 to about 5000 BP - the span

varies according to the area]. Since

those early years the discovery of the skeleton has drawn wild estimates for its

age. One Gough's Cave booklet of the 1920s said the Prehistoric Man on view was

40,000-80,000 years old, and that was twenty years after the Goughs had published

a postcard with some estimates from St. George Gray saying the man was a cave

dweller who lived between the Palaeolithic and Neolithic ages. [Today Mesolithic

is described with a time span in Europe of 11,600 to about 5000 BP - the span

varies according to the area].

So

St George Gray's was a good ballpark date as today recent dating suggests close

to 9,100 BP. Right

Arthur and William Gough credited with the discovery pose with the skull and

some of the bones. While

the skull is the most fascinating record - I think we all feel close to our own

- the fissure in the cave where it was found, the layers of stalagmite and the

sediments carrying many small artefacts have all attracted academic research from

many angles. Here is just one.

The

original entrance to the New Cave was small, only sixty-one centimtres and certainly

filled with sediment and broken limestone. When Gough cleared the debris and enlarged

the entrance he didn't take much care with notes about layers of sediment, the

natural records so helpful to archaeologists. Animal bones, human remains and

handworked filnts were heaved out in a jumble.

So

careful excavations over the past hundred years have attempted to determine how

the cave was used and as a cave-dwelling the site could have an extensive history

- there is more in KW UBSS Pleistocene discoveries

Gough's Jacobi…. Roger Jacobi of German-English

descent was a member of the Ancient Human Occupation of Britain Project

[Oxford University].

The Goughs created a small museum outside the cave, and produced postcards.

They

displayed the bones in the museum, together with an array of artifacts - some

from the cave and some from almost anywhere.

Roger Jacobi looking at the jumbled array said 'they could have been from Omdurman'.

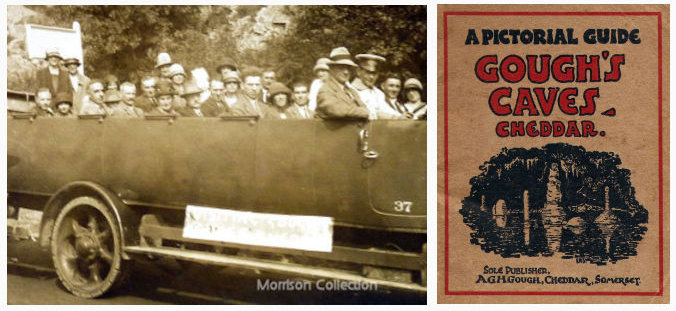

Tourists

poured into Cheddar, with charabancs of day-trippers filling the tea-rooms

and buying Cheddar Cheese - made by Llewellyn Gough born in 1869 and one of Richard's

sons. In 1927

the Goughs' lease to the cave expired and ownership returned to the Marquis of

Bath who had acquired the land..

Enter

Richard Parry - aka 'Fred'- Roger Jacobi wrote an obituary for the UBSS

Richard

Parry was the Agent for the owner. He was instructed to make a thorough excavation

of the fissure where Cheddar man was found and remove other bones left in situ

by the Goughs. The work began in November 1927 and was meticulous with Parry digging

in about fifteen centimetres. Among artefacts he located were many bones not belonging

to Cheddar Man, worked flints, and a bâton de commandement -

a carved bone of unknown use and one of two ever found in Britain. Both came from

Cheddar. Parry

found other bones and said glumly that no records had been kept of the earlier

excavations ……however very sadly Parry's own original notebooks have

also been lost. Fortunately

Parry wrote an account of his finds for the Somerset Archaeological and

Natural History Society with St. George Gray commenting on the artefacts.

Three more specialists worked on the flints and bones. The

discoveries are listed and many are illustrated. Two publications by RF Parry

1929 and 1931 now online at Somerset Historic Environment Record

(Somerset HER based in Taunton) search box 10398 references

9 and 13  Following

the Goughs' ownership more changes were made though the famous names of Gough's

and Cox's cave were kept. Gerald Robertson was appointed Manager and he was a

good friend of the UBSS as the Society continued to make discoveries - archaeological

and in exploration. 'Tratty '- our revered Prof E K Tratman working with Gerald

Robertson compiled a list of the antiquities in the cave museum. Following

the Goughs' ownership more changes were made though the famous names of Gough's

and Cox's cave were kept. Gerald Robertson was appointed Manager and he was a

good friend of the UBSS as the Society continued to make discoveries - archaeological

and in exploration. 'Tratty '- our revered Prof E K Tratman working with Gerald

Robertson compiled a list of the antiquities in the cave museum.

Right

The entrance to Gough's cave with the museum in the mid 1950s. The entrance

is being enlarged - again - see the dust

The photographs

This

is where I enter the story. My first full year with the UBSS had been one of getting

around underground as much as I could. This

is where I enter the story. My first full year with the UBSS had been one of getting

around underground as much as I could.

By

1957 I turned to being a 'Sherpa' for cave divers or 'digging' which meant spending

hours clearing tunnels aka hoping to find new caves and record them photographically.

In October 1957

I bought a British Made twin lens reflex MPP Microcord second-hand to replace

my folding Baldix, a small German camera. The

Microcord was solid and had good lenses. I took two films of about twelve pictures.

The first set was on the Baldix Negatives [labelled B ]and the second on the Microcord

Negatives [labelled M] For

close-ups of the teeth I used a supplementary lens of + 1 dioptre. My

'flash' was a hand-held 'flashgun' using flashbulbs filled with fine magnesium

wire in oxgyen. Such 'guns' held small batteries and were connected to the camera

by a short cable. An electrical contact in the camera shutter completed the circuit

and fired the flashbulb.

Professor

'Tratty' Tratman and Oliver Lloyd asked if I could take some detailed pictures

of the Cheddar Man skeleton as they needed them for research. At the same time

I was asked to give some negatives to Dr Kenneth Oakley at the British Museum

of Natural History (Now The Natural History

Museum). Black and white film usually produced a negative image from which prints

the same size or enlarged were made.

Kenneth

Oakley who was then active in the Geology Department of the Museum was known famously

for his uncovering of the Piltdown Man hoax in the early 1950s. [Wiki it]. I must

have had thoughts of a Cheddar Man hoax follow up….thinks. I cannot recall

the details - maybe I went to Cheddar by bus or on the 39 Bus to Burrington village

and then to Cheddar with 'Tratty' in his Bedford Dormobile. Anyway I knew I couldn't

afford to make a mistake, as apart from a test roll of film, these pictures of

Cheddar Man would be the first taken on the Microcord, and I had then to hand

process and print them. Professor

EK Tratman wrote what is arguably the most detailed account - Problems of 'The

Cheddar Man' Gough's Cave, Somerset KW UBSS Cheddar

Man problems Tratman 'Tratty'

being a dentist wanted the lower mandible and teeth. Oliver asked for close-ups

of the teeth and here are some of the pictures. In his paper 'Problems…'

'Tratty' said 'The social habits of Cheddar Man lncluded habitual cleaning

of the teeth. Abrasion grooves on the necks of the Lt. C, PM1, PM2 [lower] indicate

a regular to - and- fro movement of the cleaning agent, probably a twig. The mere

trace of a groove on Rt. C [lower] allows a further deduction that Cheddar Man

was probably right-handed. | | | |

View on

the Frankfort Plane | | | | | |

Footnotes

DNA Studies

have moved the story forward in several leaps. In 1999 a TV funded project found

a link between Cheddar Man and a local history teacher in the present day village

of Cheddar. In search of Cheddar Man ISBN 07524 1401 By Mick Aston, Philip

Priestley & Adrian Targett.

In February 2011 the DNA story was re-told on BBC in The History of Ancient

Britain and in early 2018 The First Brit on Channel Four TV

revealed a DNA result of dark skin and blue eyes. [So far unpublished 2018]

The

skin colour and blue eyes were not surprising as apparently it is a trait of Mesolithic

humans. A Spanish discovery of 7000 year old remains at the La Braña-Arintero

site in Leon 2008 is on record in Nature with a broad consideration of

genes in Mesolithic Europe. 26th January 2014 KW Carles Lalueza-Fox

Mesolithic European Nature

The

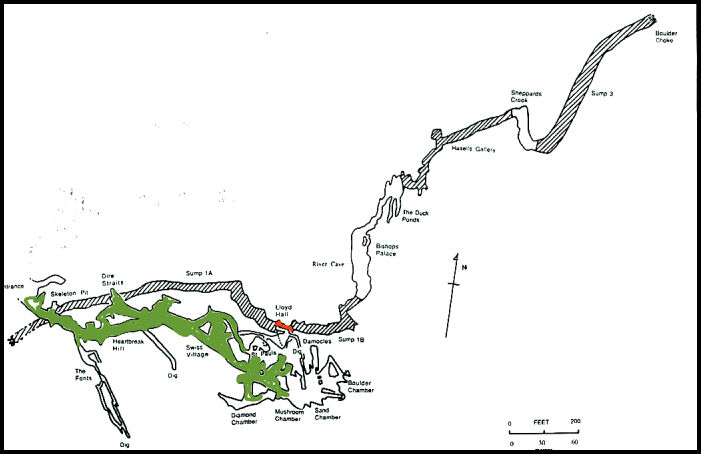

Cheddar Yeo river

Gough's New Show Cave is shaded green and as Dave Irwin says Richard Gough will

be remembered as one of the great cavers of Mendip for his efforts to open up

more chambers to the world. The Cheddar Yeo -in black - whcih begins underground

way off the map to the right has been a challenge for cave divers.

With help from the cave owners some very experienced divers have pushed the underground

limits of the Yeo more than 1090 metres or 3578 ft [2018]. In some places the

explorers have had to go down 55 metres/ 180 feet to pass from one natural

air-space to another. On the left of the map the Cheddar Yeo leaves the cave and

enters daylight to become a tributary of the Axe. In the nineteenth century the

water was used to power mills in Cheddar village Plan

adapted from one published by the UBSS

Map

of Gough's New Cave and the Cheddar Yeo - (the river section is not open to visitors)

In

my final years at the university I helped as a divers' 'sherpa' taking gear to

remote parts of Mendip caves so they could be fresh for a dive. Oliver Lloyd was

one of the team and once we practised underwater rescue in a Bristol swimming

pool. So I find it immensely gratifying that Oliver's name has been given to one

of the large chambers on the Cheddar Yeo. Red marks the spot for Lloyd Hall

a 20 metres chamber.

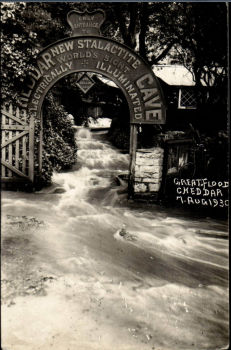

The

Great Flood- July 10th 1968 It

is worth searching the web for the Flood of July 10th 1968 when after intense

rain on the Mendips huge volumes of water inundated the main streets of Cheddar.

Any cave dweller would have been trapped and drowned. Wookey

Hole alight !

Now

….About that story of setting fire to Wookey Hole, that splendid river cave

fed by Swildon's Hole, Eastwater Swallet, St. Cuthberts' and all the swallets

near Priddy. Would you believe any story told by this gang whose leader's carbide

lamp hit the bat shit? Now

….About that story of setting fire to Wookey Hole, that splendid river cave

fed by Swildon's Hole, Eastwater Swallet, St. Cuthberts' and all the swallets

near Priddy. Would you believe any story told by this gang whose leader's carbide

lamp hit the bat shit?

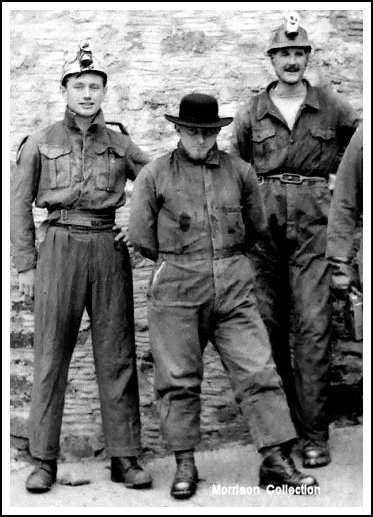

Left

to right Tony Morrison, Dr.Struan Robertson who was very attached to that 'shovel

hat' - though otherwise the gear is anything but flash and Dr.Oliver Lloyd

Let

me explain…Wookey Hole is a major tourist Show Cave about five kilometres

from Wells. As with Gough's, most visitors to Wookey see just a few chambers /

grottoes by walking on dry land but the scene is exceptional because beside them

the River Axe forms large pools of beautifully clear water. Walkways through tunnels

lead to more distant chambers but like the Cheddar Yeo in Gough's, much of Wookey

cave is either totally submerged and out of reach except by diving.

In 1955 only thirteen distant chambers had been reached by divers - that number

now stands at twenty-five [2018] - with divers having to go down to a depth of

90 metres and after passing under a lip of rock then rise again to the next air-space.

Our

small team was there in 1956 for the cave owners to try and find a dry high level

passage to go beyond the show cave. 'Dry…. high level and cave' tell the

story as we found the home of hundreds of bats. And with the bats came aeons worth's

of droppings all dry and softly spongy. Oliver's miner's brass headlamp carbide

flame hit the shit and dense acrid smoke filled the space - cough - splutter -

cough.

Today

the carbide helmet lights are banned and the cave has the status of SSSI - a Site

of Special Scientific Interest particularly for its Greater Horseshoe Bats.

My

Thanks - to Dr. Harding Jenkins for keeping me in touch with the UBSS and

to so many of the senior members in the 1950s for passing on their love of prehistory.

'Tratty' always said I had the skull of a Beaker Man - 'it's a bit flat at the

back'.

To

Andrée Rosenfeld who persuaded me to join the UBSS and who after many years

with the Institute of Archaeology in London became a Prof of Archaeology at the

Australian National University - Andrée died in 2008.

To

the UBSS and the British Cave Research Association. [{BCRA]

The Somerset HER

Heritage Environment Record / South West Heritage Trust

And,

to the owners of Gough's, for such a wonderful cave, my experiences there and

for presenting such a joy to thousands of visitors.

|