The Mystery of the Nasca Lines © Tony Morrison 1987 |

Chapter

2 — The Largest Astronomy Book |

1941 Maria Reiche arives in Nasca Europe

was at war. In December 1941 the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour and overnight

the Pacific became another arena. But in Lima daily life hardly Maria Reiche was thirty-nine when, late in 1941 she set out by bus for Nasca. 'The gods had ordained my journey and the course of my work' she has said many times, but she has never admitted the problems of those early days. In the 1940s the bus could take as long as twelve hours to cover the 275 miles.Generally the service was reliable enough, though with frequent stops and moments of concern for the survival of machine and passengers. The crosses and shrines left along the way punctuate a saga of calamities. From Ica southward the road taken by Maria crossed a broad waterless desert where a camel caravan would have completed the scene: the Spanish conquerors of Peru had introduced camels from the Canary Islands but the conditions were unsuitable and the last died in 1615.

Maria's first observations Following Paul Kosok's suggestion, Maria began her investigation by looking for any lines laid towards the rising and setting points of the sun at its solstice. The time of year, midsummer in Peru, and a cloudless sky were as Maria remembers 'just perfect' on 21 December, and within the next few days she identified sixteen solstice lines. The astronomy of the original desert people had never been given much attention, so the notion of an ancient calendar on the surface of the nearby pampa gripped the imagination of the local newspaper editor: 'Studies of Inca Astronomy in Nasca' proclaimed Noticias, Nasca's twice-a-week tabloid.

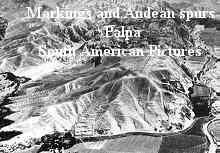

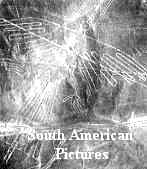

Once on the desert Maria had no difficulty verifying Kosok's original discovery relating lines to a solstice. For a few days either side of 21 December she saw the sun rising in the same place. After about a week the rising point appeared to inch long the horizon. By March, at the equinox , the sun would rise due east, announcing the arrival of autumn in Nasca. The sun's apparent movement has fascinated people of many cultures for centuries, so the idea of early inhabitants of the Nasca valley using the nearby desert like a blackboard for drawing their own version of a calendar was not preposterous. At least the construction was simple as desert is a natural scraper board. Virtually the entire area is covered by a surface layer of geologically reddened stones concealing a fine yellow earth. By clearing the stones, or even scuffing their footsteps, the line builders left their marks. The riddle lies not in how they made the lines, but why they chose the directions. Kosok put two and two together in 1941 during his visit and suggested looking for moon lines, planet lines and star lines. By the time he had involved Maria, he had already hinted that some lines pointed to the Pleiades, a group of stars recognised through the ages. Greek mythology describes the Pleiades as the seven daughters of Atlas and Pleione, of which only six of the stars can be seen with the naked eye. Legend has it that the seventh star disappeared in antiquity. In the Americas the Pleiades were known by the Mayas who built great temples in the tropical forests of Mexico's Yucatan over 1,000 years ago. Paul Kosok was well aware that the Pleiades were familiar to the early Peruvian coast dwellers, who called them Fur, and they were regarded highly by Andean mountain Indian soothsayers. If lines pointed in the general direction of the Pleiades - or of the constellation Taurus, the Pleiades' position in the Zodiac, then that had to be additional evidence for a hidden calendar. Although Maria easily identified lines which pointed in the right direction, she realised that she faced an astronomical puzzle. It concerned the change in tilt of the earth's axis of rotation - a gradual movement which takes 26,000 years to complete one 'period', before it starts all over again. The effect of this changing direction is marked by a change of the pattern of stars across the heavens - the 'celestial' sphere of astronomers. Maria realised that 'precession', or the apparent movement of the stars over the centuries, meant that a line pointing to the Pleiades in ancient times no longer pointed to them in 1941. Fortunately, she has always derived enormous pleasure from mathematics and could calculate the difference between the year when the line was drawn towards the Pleiades and the time at which she saw the stars in a particular position. So in calendar terms, the markings were another way of saying that the earth had shifted some centuries along its 26,000 year wobble. 'Another dimension - time, lies on the desert', Maria once remarked. Apart from the gruelling task of making her calculations by pencil and paper in the pre-calculator age, Maria had to take into account other technical points such as the height of the stars above the horizon and the height of the horizon above the level of the pampa itself. Both these variables needed to go into her equation or her research would be worthless. But on her first Nasca sortie, she simply did not have the necessary financial resources or instruments. The Pleiades and all they stood for would have to wait until next time. Before leaving Nasca, Maria made one exceptional discovery which has often been credited to Kosok. By the simple though determined expedient of walking to parts of the desert as much as thirty miles apart, she found lines in one place drawn along more or less the same compass angle as lines in a totally different spot. Though such a discovery may be passed over with a shrug, on the basis that some lines are bound to follow the same general direction the compass angles Maria found were far too close to suggest coincidence. During many hours of lonely hiking between one measurement and the next Maria pondered the significance of her discovery. The most obvious conclusion, she decided, was that any line drawn towards the midsummer sun was bound to have the same compass angle however far apart the views, or original line makers, stood. Drawn on a map such lines would be parallel, and as her investigations progressed Maria found many parallel lines. Such accurate parallelism over wide distances implied that line makers in different places must have been looking at the same extremely distant objects - the midsummer sun was one such object. Nearer objects, such as hills, would not account for the parallelism. Lines Maria drew on a map from two widely spaced places simply converged; she was facing a problem of logic very close to her heart, and remembers just how happy she felt: 'It was not yet my happiest moment - that came later when I was working on the animal figures, but I was very happy. It was marvellous'. Maria believed she had found proof for Kosok's 'astronomy' hypothesis; the next step was to explain the way the calendar functioned. At first she was daunted by the scale of the problem: 'So many lines and such distances' - indeed one line is twenty-five miles long. 'Then I found more animal figures, eighteen altogether, including the giant bird, the whale and the spider … and then of course I needed to find out how they were involved'. The war years in Lima By the end of 1941 Maria had finished her work in Nasca and returned to Lima to write to Paul Kosok. It was then that the full force of the war intervened and, with America involved, Kosok's Nasca work came to a halt. Kosok found he was teaching mathematics, physics and scientific German as part of the war effort, while in Lima Maria's travel was restricted. As the United States entered the war the Peruvian Government offered the American airforce a desert base at Talara in the north of the country and put travel limits on some foreigners. Maria stayed in Lima sharing an apartment with Amy whose business flourished with the wartime boom. They had many common interests, particularly music, which they heard at local concerts and from Amy's fine collection of records, notably Beethoven and Bach. Maria especially enjoyed getting out of the city to the nearby hills and mountains at the weekends, and though at times she suffered from sciatica, she rarely complained even when it slowed her walking. For the most part, Maria spent the war years in the company of British and American friends who 'offered great kindness'. For many years she and Amy shared an apartment in Lima beside the Parque de la Reserva, close to the centre of the old city. This attractive park had been laid out in 1929 in the days of President Leguía. Dominating the centre of the park stands a statue of Antonio José de Sucre, the general whose skill won the final battle in South America's struggle for independence from Spain. But while modern armies clashed across the heartland of Europe the quiet park was perfect for an evening stroll. Although Maria continued to teach, she also took on the job of book-keeping for Amy's growing business, for Amy had begun to invest in building and Maria remembers how she became involved with 'accounts and supervision'. All this activity kept her occupied and her mind off the problems of communication with her mother and sister Renate in Germany. Nasca, too, was temporarily retired. Following the allied landings in France, the war in Europe entered its final winter. In the southern hemisphere as summer approached Lima, Maria wrote a short seasonal article for the old-established daily, El Comercio. The sun and a promise of fine beach weather is a popular subject for the people of Lima, who have to endure long winter days of cool mist. 'At the end of this month', she wrote, 'we can expect a wave of warmth which comes each year at about the same time and is principally due to the changing angle of the sun's rays … at midday the rays fall almost directly from above'. The friends of the war years encouraged her to write and to think about recommencing work at Nasca. In the three years since Maria had been forced to abandon her fieldwork there had been changes in Nasca. An earthquake damaged much of the town in August 1942, reducing both the church and part of the original Hotel Royal to dust. And on the matter of the desert lines the local priest, Father Rossel Castro, had begun to form an opinion - the first alternative since Paul Kosok put forward the 'astronomy book' suggestion. Possibly influenced by Toribio Mejía's idea that the lines were sacred paths, Rossel Castro expanded on the them by suggesting that 'the paths were connected with astronomy and irrigation'. He was also concerned for the protection of the site, which faced threats from local farmers who needed land to irrigate.

At

about the same time the Peruvian Airforce and an independent air survey company

were mapping parts of the desert using specialised photography. The enthusiastic

response to the 'lines mystery' by the staff of the National Air Photographic

Service (SAN) has since become a vital part of the Nasca story. Even before Maria had the chance to return to Nasca, the lines were examined by the Peruvian Dr Hans Horkeimer, a lecturer from Trujillo University in the north of Peru. Horkheimer was returning from Chile at the end of 1945 when he saw the lines from the aircraft and was immediately fascinated. He decided to use parts of hisvacation for an excursion to Nasca and through influential contacts enlisted the help of the Peruvian Airforce. In February and March 1946 Horkheimer was given three special flights over the desert and he completed two ground excursions.

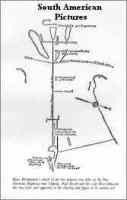

Father Rossel Castro featured in the list of acknowledgements in Horkheimer's published report. Maria did not. The details announced by Horkheimer were the most systematic to date and included diagrams support by photographs. While not setting out to oppose Toribio Mejía, Horkheimer pointed out that the lines were of many types - narrow, long, some broad, some trapezoidal, some huge rectangles - and often ascended steep hills. Horkheimer asked: 'Why?' Mejía had called them sacred paths', said Horkheimer, but 'surely "path" doesn’t embrace the variety seen in the region in question?' Turning to the Kosok astronomy hypothesis, Horkheimer was highly critical. 'Why did the ancients need lines many kilometres long or clearings a hundred metres wide to mark the position of something in the sky?' And 'Why in some places is there a veritable flood of markings, while in other places there is just the isolated triangle or rectangle?' And again: 'Why do some of the clearings which supposedly look towards the sun face instead to the south where no heavenly body graces the sky?' To

be fair, Horkheimer offered some thoughts. He asked the local people for their

opinions. 'The peasant folk', he said, were not particularly interested knowing

only that the markings were by 'the pagans' - as they called their ancestors who

were there before the arrival of the Catholic Spaniards. But from the educated

people of the valley Horkheimer found a better response. He heard how they believed

the clearings were places to hold games or were fields for cultivation, and that

the lines were directions for the well-known Inca messengers, the runners called

chasquis. More extraordinary was the assertion that the geometric drawings

were made to communicate with people of other planets. Summing up, Hans Horkheimer favoured a connection with the well-recognised ancestor worship of the ancient Peruvians. The cult of the dead and reverence for departed spirits remains strong in the Andes mountains to this day. He found numerous stone constructions among the markings which he believed were tombs and he also noticed stones gathered in heaps - each formed with a central depression 'like earth ulcers'. Horkheimer called them 'stone discs'. These he said 'marked sacred places before which the people made sacrifices, their pagan invocations and other ritual activities'. In many cases the desert markings and stone heaps were close to the widely known cemeteries of the ancient Nasca culture. 'The clearings', Horkheimer wrote, 'were meant for sacred gatherings and the lines were used for dances - the ritual dances of ancient Peru were performed by one person following another in the form of a chain'. Almost every aspect of ancient lore apart from astronomy was embraced in Horkheimer's conclusion. He emphasised the way the lines could be a family tree. 'Each line belonged to one family and the lines leading to the clearings decided the origin and kinship of the people who gathered there'. Horkheimer returned to Trujillo preparing to announce his discoveries and conclusions just as Maria was setting out to return to Nasca. A race to be first with the solution captured the imagination of the Peruvians, and the newspapers in Lima and Nasca were quick to report every fresh story and twist to the opposing theories. Return to Nasca Maria

arrived in Nasca in June in time to watch the midwinter solstice. Maria

could not afford to stay long in Nasca and, relying as she did on her meagre pay

as a teacher and out-of-hours work for Amy, was forced to return to Lima. Next into print was Father Rossel Castro who was quickly gaining fame as a local expert and archaeologist. He gave Noticias a résumé of the story and outlined Horkheimer's work pointing to the probable kinship connection. Then he moved on to the lines, pagan gods, stone heaps - which he called apachetas, and finally the astronomical purpose. 'The 'monument', the priest repeated his call, should be declared as an 'archaeological monument' A feature by Hans Horkheimer followed in El Comercio. He described his days toiling on the pampa when he and a colleague, Varona, had once struggled back to the road and stopped a car to hitch a lift. According to Horkheimer the driver, a French lady, had said: 'For the love of god just what are these things in the desert?' Horkheimer, 'dust covered and exhausted', continued his story with an account of the markings and his interpretation. But the Horkheimer theory, even with the overtones of sacrifice and ritual, never gripped the Peruvian imagination. Perhaps the suggestion of ancient astronomers hunched in darkness and sighting along the lines was more appealing. And certainly Maria kept the 'sunrise and solstice' interpretation firmly in everyone's mind. One

of her articles for El Comercio turned closed to Lima and the astronomical

alignment of Pachacámac, an ancient adobe mud-brick pyramid some fifteen

miles from the city. Pachacámac, a favourite for tourists even then, has

been damaged by the rain which occasionally strikes the desert. It was an important

shrine for the coastal people and was enlarged by the Incas when they invaded

the region in the second half of the fifteenth century. Looking at the walls of

Pachacámac, Maria found some of them to be directed to the solstice sun;

'The building was one of the finest testimonies of the ancient astronomers'. The newspaper editors never failed to keep the Nasca story in front of their readers, and by 1937 Maria had made her name in Peru. She confided jokingly at a party in Lima: 'I'm a celebrity now', but outside Peru the story was different; the mystery of the desert markings still had to make an impact, and that fell largely into the hands of Paul Kosok who was waiting in New York for funds to support further desert studies. Kosok never sat idly, and in 1937 he wrote about the Nasca lines for three American magazines, including Life; each magazine also published photographs, and with the publication of these pictures the Nasca lines and Kosok's portrayal of their mysterious astronomical possibilities the seeds of world interest were truly sown. But international fame did not touch Maria and she had to survive on a shoestring while somehow clinging to her place as the Nasca front runner. Time was on her side and she had plenty of it to make excursions to the pampa. What she did not have was money, and though San Marcos University in Lima - the oldest in the Americas - promised a small grant and a theodolite, Maria had to take into account months of costly travel. To eke out her slender budget she taught, translated and worked for Amy who also lent money for the fieldwork. Far more important than the money was Amy's tireless companionship and encouragement throughout many long expeditions. Eventually the San Marcos grant was arranged, the debts repaid and the theodolite delivered. In Nasca Maria was given the use of a truck owned by the town, she gained the unreserved backing of a colonel from the Army Geographical Service on location there, and slowly her confidence rose. The Nasca lines cover a large area, perhaps more than five hundred square miles, and Maria planned to explore much of this before Paul Kosok's impending return. Her 1941 investigation had been centred on the lines near Llipata, twenty-seven miles from Nasca. At that time she used the farm or hacienda of San Javier as her base. For the 1947 expedition she intended to examine in great detail two areas: one at Achaco only four and a half miles from Nasca, the other a pampa overlooking the Ingenio river valley at San José. It is this San José pampa which has finally brought the Nasca lines to world attention. The Achaco site had many advantages; top of the list was its accessibility. Maria could walk from the Hotel Royal in less than an hour. Once past the last cotton fields the edge of the valley signals the beginning of the desert and this was where Maria found many types of line and an animal figure known as the whale. Altogether in this one area lay ten large clearings, one of them nearly nine hundred yards long. All the clearings were linked in some way to narrow lines and many were set close to hills. From one small group of isolated hills a perfectly straight line led unbroken for some three miles. Maria plotted and measured all the markings and produced the first plan of this site. On the other side of the same desert pampa, the San José complex offered a far greater wealth of drawings. Maria had founds some of them in 1941 when she briefly visited the spot. One massive clearing dominates the western side of the desert highway, while east yet more lines, spirals, a huge bird with a zig-zag neck and some very clear trapezoidal clearings stretch to the foot of the Andes mountains. It was in relation to this site that Hans Horkheimer had questioned why so much was needed to make astronomical observations. Once again Maria set about the arduous task of plotting the markings on a map, though she now had some excellent aerial photographs from SAN to guide her. Other studies she made at this time related to a re-examination of her compass angles to find those along which the majority of lines were laid down. Every scrap of information was noted carefully, often with the assistance of local Nasca people. One young man who helped in those early days was a student, Antonio Cordova, who was taking a correspondence course in photography. Among a number of photographs he took was one which appeared in El Comercio of Maria at the top of a step ladder on the pampa.

In the photograph, Julio Fernandez, manager of the Hotel Royal, was helping to hold the ladder steady. 'They were always willing and very quick to understand my work', Maria remembers. 'They knew I couldn't pay and still they offered to come. I was showing them something new on the pampa every day.' While on the surface her work progressed well, Maria was aware of criticism and sensed undercurrents of disapproval. After all, she rationalised, she was not an archaeologist and she was getting a great deal of publicity. But she could not let such thoughts deter her progress and forged ahead. She did not stop even when, in early 1948, Amy took a short trip to the Amazon jungle on the far side of the Andes mountains. But some months later, when Paul Kosok had still not arrived, her lack of money and failure to get the results she expected almost forced her to give up.

So when eventually, after a seven year absence, Paul Kosok arrived in Lima, Maria greeted him with mixed feelings. For all those years she had worked alone on the problem and suddenly here was Kosok, the originator of the astronomy theory, with all the international weight behind him. Now he could offer her expenses and take all the credit. But more than ever before she did not want to give up her very private happiness on the pampa: 'It was a very special beauty, something I can't describe'. It was agreed that Kosok and his seventeen year old son Michael would rent Maria's Lima apartment while she continued to work in Nasca. The extra money would help towards her Nasca costs. This time, when Maria returned to the pampa, she was equipped with a Swiss theodolite on loan from the Army Geographical Service, and she was determined to get a result before Kosok. Aside from the personal challenge, Maria needed to generate some international scientific interest in the subject. Academic opinion at the time considered these mysterious desert lines were a curiosity to be pushed under the mat, although coupling them with Kosok's name would give them a certain respectability. Together they planned an article for the reputable American journal Archaeology. Paul Kosok and Michael arrived in Nasca to find Maria 'out of town'; they installed themselves in the new Tourist Hotel and Kosok called on Agustin Bocanegra, the friendly owner of Noticias, and waited for Maria to return. Once reunited their work apparently went well, though Maria soon headed back to the pampa to continue her personal observations. Kosok and his son went in another direction. On her return to Lima, Maria told her friends that she would have to come to some agreement with Kosok; on the one hand he had introduced her to the lines while she, on the other, was dedicating her life to the problem. Despite a certain tension between them, at least the lines of communication never broke down completely and Maria agreed to join Kosok in northern Peru the following year. He was preparing the manuscript for a book and once more asked her for help with translations. There was also the Archaeology article to consider. The

next two years were filled with a mixture of frustration and success. Early in

1949 Maria set out for the mountain town of Cajamarca in northern Peru. Cajamarca,

9,000 feet up in the Andes, spreads across a lush green Kosok chose to write in Cajamarca, for not only was the cost of living lower, it was also within a short air flight from Trujillo where had good friends at the university. Maria found herself translating descriptions left by Spanish writers, mostly priests, who travelled with the soldiers and settlers. The 'Chronicles'. as these fascinating documents are known, are scattered throughout the libraries of the world and more pages come to light each year. Meanwhile at the same time as puzzling over the intricacies of seventeenth century Spanish, Maria was working non-stop on her private project. For some time she had been planning a small book she intended to publish in Spanish and English editions. She wanted this book to be the first, and thus potentially the most important account of the issues at Nasca. Both editions were to be illustrated with the latest photographs and her own unique maps. The

Spanish edition, a booklet with twenty-five pages of description and many original

photographs, was the first to be published. The Lima printer undertook the work

on credit and Maria was responsible for all the preparations including the design

of the cover. Only 1,000 copies were printed and brisk sales covered the costs

in a month. 'That was lucky', Maria admits, 'I had no money so I was

living on grapes and a few biscuits'. But this first sign of success gave her

the confidence to present an English edition of 2,000 copies. The contents of the English edition are somewhat different from the Spanish, which is aimed more at readers familiar with the places and people of the day. Friends gave Maria plentiful advice and were often highly critical of her style, but she shrugged it off and the English edition benefits from her 'no-frills' clarity. She devised the title Mystery on the Desert and the book became an immediate best seller, with the Peruvian Government ordering the first hundred copies before it had been printed. Mystery on the Desert fills one of the biggest gaps in the story of the Nasca lines because within it Maria described the pampa as she found it. The other archaeologically oriented descriptions of Nasca remains and excavations concern the valley or the nearby graves. Maria's book says something about the pampa - the flat 'blackboard' outside the town, as the newspapers were beginning to call it. After describing the shapes, conditions and reasons for the survival of the markings, Maria turned to the centres from which a number of lines radiate. 'From the air or on a small scale maps these centres appear as sharp points. In reality they are central areas', she wrote. Such central areas were mounds or small hills with as many as twenty lines around them and, as she said, they are 'a common feature'. She called them starlike centres. Another of Maria's early observations was the way that designs were laid one on top of another: 'The borders are either interrupted, forming entrances or exits' - from one pattern to the next - or the edges of one or both designs continue uninterruptedly inside each other', implying an overlap possibly of tracings of different ages. Today such information is invaluable, bearing in mind the rapidly changing face of the site. On the subject of any relics she found on the lines or anything which could have been left there by the line makers, Maria mentioned stone heaps and described pottery, most of it broken decorated ceramic belonging to different periods of the Nasca culture. Then she spoke of how 'vessels had been found intact on the surface and apparently in the same place where they were left perhaps a thousand years ago'. The book records how 'stones with designs on them were found in two places'. One stone held a design representing a snake's head and a small trophy head, no doubt recalling the Nasca custom of collecting heads of their enemies. Maria's books give credit to the explanation of Dr Paul Kosok, though in her critique in Mystery she commented that 'simply having lines dividing the year into two halves marking the solstices of June and December was insufficient proof for the astronomical meaning of the markings'. Then, almost as an afterthought, she reflected that facts pointed that way and so 'an attempt should be made to reach a definite conclusion for or against the theory'. With the success of her books the 1940s finished well for Maria and she began to talk of a 'better, perhaps an international, edition of Mystery on the Desert. Kosok left Peru for the last time and Maria, who had assumed the character of a perpetual student, returned to the desert. Early in 1950 she arrived at a settlement by the peaceful river of Ingenio fifteen miles from Nasca. The pampa of San José was only a few yards from the road and here Maria found the adobe built store of a local hacienda whose owners, three Englishmen she had met on previous visits. One of them Lyndon Evelyn, remembered how Maria asked if she could use a room in their store as a base as she needed somewhere to leave her maps and instruments when she was away in Lima; a bed and blanket would also be useful. At first Evelyn and his colleagues refused, believing the isolated store could be unsafe overnight, for bandits and robbery were common in those remote parts of Peru. 'She was very persistent and begged us to lend a room', Evelyn said. 'It was no place for a lady but she was prepared to take the risks and in the end we gave in'. The one room Maria chose at the rear of the store was dark with an earthen floor and badly fitting door. But in every other way it was perfect. At last she was ready to stay until she found the answer to the desert mystery.

TO BE CONTINUED....

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

changed.

Peru even prospered.

changed.

Peru even prospered. Once

across the desert the old road climbed the desolate Santa Cruz range before descending

abruptly to the broad Rio Grande, which takes the Nasca river. The rugged Andean

foothills, a barren stony desert, and valleys filled with neat orange groves were

Maria's first taste of this part of Peru and she immediately sensed it could be

her next home. But there were drawbacks, and the hotel in Nasca where she stayed

she remembers well as 'the original Royal - a filthy and noisy dump'. Nights

in the Hotel Royal were so disturbed that, after a short rest, Maria always left

her room in the middle of the night to look for a passing truck to take her to

the desert pampa for sunrise. 'The drivers were kind to me', she said,

'they had to drive more than six hundred miles across the desert from Arequipa

to Lima on such poor roads, yet they still bothered to take me to the pampa'.

Once

across the desert the old road climbed the desolate Santa Cruz range before descending

abruptly to the broad Rio Grande, which takes the Nasca river. The rugged Andean

foothills, a barren stony desert, and valleys filled with neat orange groves were

Maria's first taste of this part of Peru and she immediately sensed it could be

her next home. But there were drawbacks, and the hotel in Nasca where she stayed

she remembers well as 'the original Royal - a filthy and noisy dump'. Nights

in the Hotel Royal were so disturbed that, after a short rest, Maria always left

her room in the middle of the night to look for a passing truck to take her to

the desert pampa for sunrise. 'The drivers were kind to me', she said,

'they had to drive more than six hundred miles across the desert from Arequipa

to Lima on such poor roads, yet they still bothered to take me to the pampa'. The

writer gave the Incas, a mountain people, the credit for the desert markings,

apparently forgetting that Nasca itself had a perfectly respectable history to

call on: '18 December - Miss Maria Reiche a mathematics teacher is in Nasca

to take measurements. The work will offer people everywhere some completely new

ideas about the degree of Inca civilisation'. The next edition of the paper,

Number 191, price ten centavos, continued the Inca theme, describing the lines

as astronomical studies of the Incas: 'Paul Kosok found clear signs of the

rudiments of Inca astronomical control on the hilltops and then on the pampa'.

The writer went on to explain how Maria Reiche had studied the hitos or boundary

marks which were known to exist in the surrounding hills. These hitos are heaps

of stones resembling cairns dating from long ago and were well-known landmarks

to the Nasca people. The mere fact that two foreign experts had bothered to take

an interest in the local relics added weight to the news.

The

writer gave the Incas, a mountain people, the credit for the desert markings,

apparently forgetting that Nasca itself had a perfectly respectable history to

call on: '18 December - Miss Maria Reiche a mathematics teacher is in Nasca

to take measurements. The work will offer people everywhere some completely new

ideas about the degree of Inca civilisation'. The next edition of the paper,

Number 191, price ten centavos, continued the Inca theme, describing the lines

as astronomical studies of the Incas: 'Paul Kosok found clear signs of the

rudiments of Inca astronomical control on the hilltops and then on the pampa'.

The writer went on to explain how Maria Reiche had studied the hitos or boundary

marks which were known to exist in the surrounding hills. These hitos are heaps

of stones resembling cairns dating from long ago and were well-known landmarks

to the Nasca people. The mere fact that two foreign experts had bothered to take

an interest in the local relics added weight to the news.

The first of many thousands of SAN aerial pictures were taken over the Nasca desert

in 1944 and, together with those taken by various photographers travelling on

Faucett flights, they have become a permanent record of the desert.

The first of many thousands of SAN aerial pictures were taken over the Nasca desert

in 1944 and, together with those taken by various photographers travelling on

Faucett flights, they have become a permanent record of the desert.

The

pampa was cool and the air wonderfully clear. The Noticias of 27 June was

headlined: 'Interesting archaeological revelation discovered by Miss Reiche'

and the article, signed by Maria, talked of 'being close to the solution,

or at least a partial solution, to the secret of the Inca Roads and the geometric

figures found by Mr Kosok…' She continued by explaining how many lines pointed

to the sun around the important date of 21 June. 'One day we expect to decipher

the puzzle - if God so wishes'.

The

pampa was cool and the air wonderfully clear. The Noticias of 27 June was

headlined: 'Interesting archaeological revelation discovered by Miss Reiche'

and the article, signed by Maria, talked of 'being close to the solution,

or at least a partial solution, to the secret of the Inca Roads and the geometric

figures found by Mr Kosok…' She continued by explaining how many lines pointed

to the sun around the important date of 21 June. 'One day we expect to decipher

the puzzle - if God so wishes'. However,

in the next issue of Noticias she wrote a letter to the editor, Agustín

Bocanegra, expressing her thanks to the people of Nasca and apologising because

she had not been able to call personally and tell the newspaper about her discoveries.

She went on to say that the results of her research were positive and that she

had seen the sun rising exactly at the end of one of the Inca solstice lines.

'I hope to return very soon - Hasta la vista, Maria Reiche'.

However,

in the next issue of Noticias she wrote a letter to the editor, Agustín

Bocanegra, expressing her thanks to the people of Nasca and apologising because

she had not been able to call personally and tell the newspaper about her discoveries.

She went on to say that the results of her research were positive and that she

had seen the sun rising exactly at the end of one of the Inca solstice lines.

'I hope to return very soon - Hasta la vista, Maria Reiche'.

Some

of the previously silent critics began to voice opinions. Among them was Father

Rossel Castro, who wrote to Noticias saying that in her work Maria was

to some extent changing names of local places. If this continued it could make

future studies difficult.

Some

of the previously silent critics began to voice opinions. Among them was Father

Rossel Castro, who wrote to Noticias saying that in her work Maria was

to some extent changing names of local places. If this continued it could make

future studies difficult. valley,

famed locally for its rich dairy products. The cool climate suits the almost European

way of life set among colourful Quechua Indian homes. The Spanish invaders settled

there after Francisco Pizarro and his small band took control of the Inca Empire.

Atahualpa was ambushed and

captured just outside the town.

valley,

famed locally for its rich dairy products. The cool climate suits the almost European

way of life set among colourful Quechua Indian homes. The Spanish invaders settled

there after Francisco Pizarro and his small band took control of the Inca Empire.

Atahualpa was ambushed and

captured just outside the town.