University

of Bristol Trans-Continental Expedition 1960 — 61 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

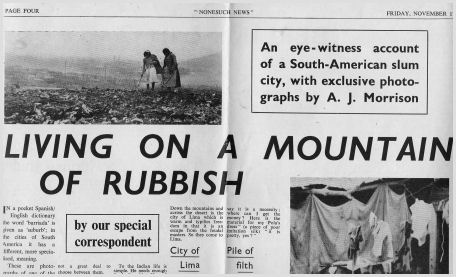

Living

on a Mountain of Rubbish | ||||||||

This feature story appeared soon after the Expedition returned to Bristol and Malcolm was looking for a job. He decided to publish the report anonymously as he was concerned that his views on the pitiful life in the Lima slum could reflect badly on a country he had enjoyed visiting. But at the same time he knew that as a writer he had to make a comment. Back in 1961 journalism critical of governments was rare - today it is taken for granted to the point of overkill. So here is a report on a way of life by a man who was sensitive to the appalling conditions for the poor who lived on a mountain of rubbish created by the wealthy. Perhaps it is worth reflecting that in 1961 the population of Lima was 1.6 million. By 2014 the year of Malcolm's death the number had risen to 9.7 million. El Montón the Mountain of Rubbish has gone only to be replaced by others. Tony Morrison co-founder of Nonesuch Expeditions and Editor was the photographer | ||||||||

In

a pocket Spanish/English dictionary the word 'barriada' is given as 'suburb';

in the cities of South America it has a different, more specialised meaning. [now

the name is pueblos jovenes - 'young towns] In

a pocket Spanish/English dictionary the word 'barriada' is given as 'suburb';

in the cities of South America it has a different, more specialised meaning. [now

the name is pueblos jovenes - 'young towns]These are photographs of one of the several barriadas on the outskirts of Lima; it is the largest, it is probably the most unpleasant, but there is not a great deal to choose between them. The people who live here - 50,000 seems to be a conservative estimate - come from the country, from the mountain plateaux and valleys. To the Indian life is simple. [the Quechua people of the Peruvian Andes] He needs enough food for himself and family, and he is beginning to appreciate the concept of freedom. But on the mountain plateaux (above 13,000 feet) the climate is cold and unkind to crops, and there is not enough food. Down the mountains and across the desert is the city of Lima which is warm and typifies freedom in that it is an escape from the feudal masters. So they come to Lima. City of Lima Lima, by popular accord, is one of the most pleasant cities in South America. It lacks the superb geographical setting of Rio de Janeiro and the history of Cartagena, but it is … pleasant; there are dignified squares, long avenidas, with trees and gardens all well watered. The sun shines almost all the year; it never rains. Costs are not so prohibitive as in many South American cities, it is possible to enjoy oneself for a moderate sum … moderate to us, that is. So the Indians come to Lima looking for some release from their drudgery, one presumes. But certainly looking for work. And not finding it. Houses are even more difficult to find; so they live in the barriadas, on the very edge of the city, in between the city and the desert. Metal sheet The barriada shown here is known as 'El Montón', it takes its name from the enormous city refuse dump which is its dominant feature.

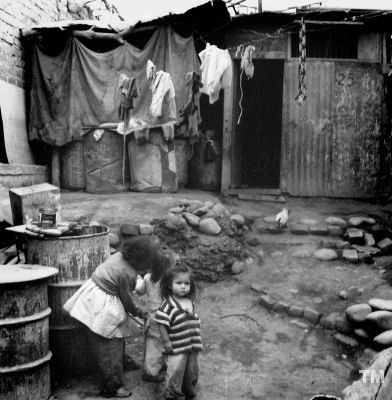

One day only The mother in one of the homes - otherwise a happy and determined woman - bewailed that her son must have a uniform for school - "for one day only, but they say it is a necessity; where can I get the money? Here is the material form my Pola's dress" (a piece of poor imitation silk) "it is pretty, yes?" Pile of filth Deeper into the settlement, the house walls are now made from scraps of wood, sheets of metal, hessian, plaited leaves, the roofs are of hessian, cardboard or rags. They look like battered cardboard boxes with strips half torn off and hanging over the edges. The smell in the streets is becoming more unpleasant, we are nearing the dump, El Montón, itself. The houses are smaller, even poorer, some of them backing onto the pile of filth. Odds and ends Everywhere are heaps of 'saleable' metal and other odds and ends rescued from the rubbish. Rags extracted from the dump, have been washed and are hanging to dry on close set lines; later they will be torn into shreds and sold for pulping. If actual clothes should be hanging nearby it is difficult to tell the difference; when the rags are draped over the flat roofs to dry it is impossible to tell where roof ends and rags begin. Pigs and dogs

The pigs belong to a wealthy man who has bought the rutting rights; it is hard to see why the people do not kill and eat them. El Montón is now being cleared. Part of a socially conscious scheme, perhaps, like the provision of occasional water taps in the streets? But the people of the barriada do not see it that way - "They are taking away our only livelihood," they say. "A millionaire has bought it to make fertiliser"; an improbable story, but indicative of their frame of mind. Clean air Of all underdeveloped countries it is possible to say that the conditions of such people in the cities, deplorable though they may be, are hardly worse than those in the villages. Yet it is neither romantic nor reactionary to say that the differences are great. In the villages, though the peasants are exceedingly poor, they breathe clean air. In countries such as India and Bolivia they own their own land even if it be of little value; and they live a traditional life, a life they understand. Progress is inevitable, in fact absolutely necessary, but the improvements must be made where the people live and within the existing framework. To dangle a carrot before the nose of a donkey is a cruel form of coercion (Dante used it as a torment in hell), but at least there is intention of feeding the poor animal eventually. Way of Life Our carrot is our way of life, a tenuous thing and available only under certain strict conditions. The Indians do not qualify. We turn them into unskilled labourers, or at best servants. What is more, to the uneducated, ours is a wholly materialistic philosophy, a rickety prop for a new life. Our clear duty Not to put too fine a point on it, these people, and millions like them, have been betrayed. Perhaps the mistake was originally in the past, but its effects remain. Devoted

work is being done by individuals to whom the 'white man's conscience' is an intolerable

burden. Surely it should not be necessary. It is our clear duty to expiate the

'mistakes' of our ancestors; and it is the duty of our civilisation as a whole | ||||||||

|

The

streets are of earth strewn with rubble and unwanted scrap and the houses mean

and flimsy. On the edge the aspect is reasonable (at least, seems so on the way

out), because the houses are of brick - mud brick, one layer thick, and erected

by the owner, but nevertheless, brick. Here one even sees an occasional television

aerial, some of the people actually have jobs - but the roof on which it is erected

will be, at the best, loose corrugated metal sheet, and is much more likely to

be hessian sacking.

The

streets are of earth strewn with rubble and unwanted scrap and the houses mean

and flimsy. On the edge the aspect is reasonable (at least, seems so on the way

out), because the houses are of brick - mud brick, one layer thick, and erected

by the owner, but nevertheless, brick. Here one even sees an occasional television

aerial, some of the people actually have jobs - but the roof on which it is erected

will be, at the best, loose corrugated metal sheet, and is much more likely to

be hessian sacking. Here

is the mountain of filth; and there are the scavengers … human and animal.

Men, women, children, dogs, monkey, pigs, fowl, all scratching together at their

only sour of income or food. The pigs are large and nasty, the dogs thin and nasty,

the stench is virtually unbearable, the pickings are very small.

Here

is the mountain of filth; and there are the scavengers … human and animal.

Men, women, children, dogs, monkey, pigs, fowl, all scratching together at their

only sour of income or food. The pigs are large and nasty, the dogs thin and nasty,

the stench is virtually unbearable, the pickings are very small.