University

of Bristol Trans-Continental Expedition 1960 — 61 | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Fortress The nearby fortress of Sacsayhuaman is a superb example of the even older monumental style. It is built on a mound with three concentric circular walls of white granite and promenades in between.The outer wall is of zig-zag design and is a good 20 ft high; some blocks have been estimated to weigh 361 tons. Legends say that during the construction a block weighing 1000 tons ran amok and killed 300 indians.

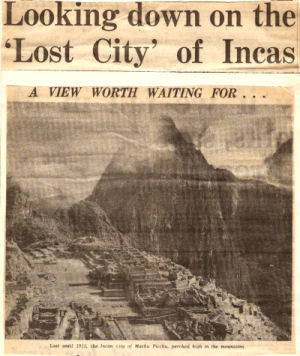

Machu Picchu was the ultimate justification of this type of scenery, it was lost until 1911, and it is something of a wonder that it was found at all. It is perched on a densely wooded hill, 1000 feet up (the road has 14 hairpin bends), and is within an almost circular sweep of the river. From below little can be seen except some of the agricultural terraces but above are the remains of a small city, rows of houses and workshops, temples, palaces and watchtowers. It was a place for a mountain race - there are 109 different flights containing over 3000 steps. Two of us took a tent along and camped overnight among the terraces overlooking the city. This was no place to stroll around in the dark, sheer drops of 1000 feet presenting themselves at most corners. Worthwhile But

the morning's view was worth it. We awoke at five and set up our cameras. The

city was a hundred feet or so below and on its far side rose the sheer pinnacle

of Huaynapicchu 1000 feet , higher with its lookout place. People have lived in

this eyrie of a city food that made the city self-sufficient was planted on the

walled terraces (from six to 15ft wide, cut out of near vertical slopes), water

flowed through the 17 channels in the Fountain District and in the Temple (thought

Hiram Bingham the discoverer tame snakes performed oracle according to which exit

they chose from a chamber.

But the essential character cannot be changed, Machu Picchu and all it has meant is not to be destroyed by mere tourism. To get a good look at it we climbed Huaynapicchu. No mountaineering was necessary since paths and steps have been cut; but these are often very steep and moss-covered and are rarely more than 15 inches wide. Through the bushes, growing on the verge less than a foot wide we could see the river way below; by the time we reached the top the sheer drop must have been 2000 feet. The altitude ranged from nearly 9000 to 10000 ft, so the climb was somewhat onerous(particularly when carrying several cameras each), our muscles needed frequent rests. We were all the more surprised there fore to be overtaken at a gallop by 15 men talking volubly in Spanish as they went (we had hardly enough breath to keep our lungs working!).

Machu Picchu to Lima... where we met two more intrepid fellows, an Englishman and a Canadian, Robbie and Ray who had teamed up in Panama and walked through the Darien Gap. This 250 miles of jungle and swamp has successfully defied all attempts to cross it by car - one did get through but the expedition cost £17,000 and the car was carried most of the way by 250 native porters.

We saw

a little more of Lima this time than during our trip up to Bolivia. It is a booming

city set in a country of great poverty and potential unrest. There are many contrasts;

Lima is virtually an oasis only eight miles from the coast and surrounded on all

other sides by the Atacama desert. Conspiracy In the largest, 50,000 people are calculated to live, it is called 'El Monton' since it is built onto a gigantic exposed refuse dump of that name.The disgusting odour of this heap permeates the whole area, dogs, pigs, donkeys and fowl scratch in it, and many jobless people root through seeking saleable or edible refuse. "El Monton" is now being cleared; the people say it is a conspiracy to deprive them of their only source of income. Among the worst slums we found a devoted group who were members of "Emaeus" the society to help less fortunate people, and inspired by the work and example of Abbe Pierre in France. The accent is on understanding the problems; really to understand one must live with the people, live their problems and their hardships. The leaders are a married Canadian couple but many of the workers are from s Swedish society called "The Swallows" Ran homes Most

were young girls; one Marianne, was engaged to an Italian boy and had worked as

a teacher and a mental health nurse, she was to stay in Lima for at least a year

in charge of a house filled with 61 children whose parents either could not, or

would not, support them. Editorial note: The Spanish climbers were from the Expedición Espanola a los Andes 1961 - from Barcelona | ||||||||||

| NEXT REPORT 18 | ||||||||||

1961

FILM of MACHU PICCHU | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

On

leaving Bolivia our first stop was in Cuzco, the old capital of the

Inca Empire. In Cuzco the remains of Incan and pre-Incan architecture still stand,

the only destruction has been caued by man, not by time. During the 1950 earthquake

many Spanish colonial buildings were demolished, but not the old wall on to which

the Christian churches and palaces were often built. The church of San Domingo

for example is virtually in ruins but the superb, curved outer wall of 'Inticancha'

(the Sun's yard) on to which it was built still stands.

On

leaving Bolivia our first stop was in Cuzco, the old capital of the

Inca Empire. In Cuzco the remains of Incan and pre-Incan architecture still stand,

the only destruction has been caued by man, not by time. During the 1950 earthquake

many Spanish colonial buildings were demolished, but not the old wall on to which

the Christian churches and palaces were often built. The church of San Domingo

for example is virtually in ruins but the superb, curved outer wall of 'Inticancha'

(the Sun's yard) on to which it was built still stands.