University

of Bristol Trans-Continental Expedition 1960 — 61 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Published 10th March 1961 | ||||||||

The village of Pusegaon, the centre of our observations, is 90 miles south of Poona, itself 110 miles inland from Bombay. This group of villages, Pusegaon, Koregaon and Aundh, thus lies on the upland plateau immediately to the east of the beautiful mountain range of the Western Ghats. The

climate from the view point of holidaymaking or relaxation is nearly perfect;

the days not too hot, the evenings delightfully warm, and every night there are

superb technicolour sunsets over the distant blue hills. But as far as farming

goes there is not enough rain around 20 in. a year and most of that at one time

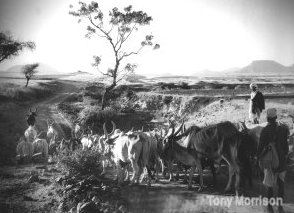

in the monsoon season. Our district lies on the fringe of the easily cultivable land in fact is classed as semi-barren; water and irrigation are the chief concerns. Moving away from the few parched rivers the differences in type and quality of the crops can be seen, from the profitable sugarcane and potato, to wheat and greater millet, then these in poorer quality and yield, and to spiked millet and other hardier but less valuable grains. Driving east for only a few hours one can see the whole pattern of cultivation change as the land becomes more parched until it can no longer support crops and the only life is the occasional herd of half-fed goats.

Begging rare The people of this area are the Marathis, whose history is as interesting as any in India.Once they were a warrior people with a large Empire; the tradition of militarism has remained. Recruiting was very heavy here in both the first and the second world wars and one can detect a typical inheritance from the years of discipline in that the people are cheerful and hardy and uncomplaining. Although there is much poverty, begging is rarely seen in these villages. Also, as we were soon to discover, they are most friendly and hospitable. Due, I suspect, to a fine piece of work by the Central Office of Information, an article announcing our coming and describing our project was published in the local-language newspaper five or six weeks before we actually arrived. Thus everybody was prepared and eager for our coming. We were able to make contact immediately with the Government officers, such as District Magistrate, Development Officers, Social Workers and with the Field Research Supervisor from the Economic Institute at Poona, Mr Jogiekar, and with teachers, doctors, landowners, farmers and all the people of the village. Plans had already been made, there was a great determination that we should miss nothing. In India there is a system of Inspection Bungalows for the use of travelling Government officers. Having established ourselves on a semi-official basis, we occupied on of these in Koregaon, 10 miles from Pusegaon, where there is no such Bungalow and the people are too poor to offer alternative Accommodation. Also we need privacy in which to work, and somewhere safe to store our equipment. Our days consisted of sorties out from this base, visits to local industries and schools, interviews with Government officers, local agriculturists, teachers, school children etc. Conservation Pusegaon was our main interest. It is a village of 2,500 people. As with all Indian villages, its physical size is much less than expected, but, of course, Hindus live a family life in its extremest form three or four generations under one roof and for a poor family, a small roof has to suffice. We

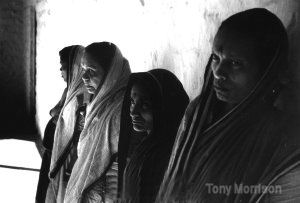

approached Pusegaon over a bridge. The river-bed is wide, but much of it is pebbles,

little water flows. What does exist has been conserved by irrigation channels

Across the river the village starts, the huts coming down almost to the water. But the bank rises steeply and there is an immediate right-angled bend; thus little can be seen of the village. The houses are simple. Most are built of rough stone or wood slats covered with an earth and dung mixture, many of the roofs are thatched, with straw or plaited palm leaves and often this too is spread with dung. There is no glass to be seen, where there are windows these are merely barred and shuttered; but most buildings have none and must use the doorways for light and ventilation. Illumination is by oil lamps, some free burning and some under pressure; many accidents are caused by continuing to use old and rusty equipment, the thatch burns easily and the loose and flimsy clothes are hazardous. On one side of the square is the Dispensary used by the doctor for consultation and treatment. It is an old, low building with a thatched roof (unsanitary thought our doctor), its walls were once whitewashed and now carry posters about tuberculosis and family planning. On the other side of the road is the Police Station, a single-storied building with a tiled roof that sweeps down over the verandah in front of which are steps and flowers. Over beyond it is a large circular well surrounded by a 2ft. stone wall and with the usual drum, rope and bucket; just adjacent a pile of dung is drying in the sun, and nearby is a loose heap of wood in which rats can be seen. Animals are all over the place, walking, straying, sleeping bulls, cows, bullocks, sheep and goats and many unhappy looking dogs. The riverbed is wide, but much of it is pebbles, little water flows. What does exist has been conserved by irrigation channels and artificial pools, and in these, and in the river itself, people are washing their clothes, their cattle and themselves. On the left are many tall trees in which peach-coloured flags are flying indicating that a temple is close by, and down the road towards us, flooding around the many led and wandering beasts, was a flock of sheep guided casually by a shepherd in an impressive red turban and a small boy with a long stick. Weekly bazaar We nudged our way through the sheep and up into the village. The road jinks left and right around some two-storied houses (one belonging to the leading doctor, we discovered), then runs straight for about a quarter of a mile. It is lined with low huts and a few shops and half way along is a square with some important looking buildings, beyond this there are huts on one side only until the road divides and a new concrete bus shelter marks the end of the village. The road is a narrow ribbon of tarmac with wider strips of dirt and stones on either side; on these, and in the square, the weekly bazaar is held, often overflowing onto the road itself. On these occasions all necessary goods and articles can be bought, and even a few luxuries; kitchen utensils in a great variety of shapes and sizes, mainly in earthenware, but also some of aggressively shining brass; cloth for saris and dhotis (loose garment for masculine legs); small articles such as mirrors and combs, gaudily painted; and many different kinds of fruits and vegetables. On bazaar day the village is crowded with people from the surrounding district, all in their brightest clothes, the food sellers sit crosslegged behind their pile of red chilis, and colourful fruits which are laid out on rugs with the handscales ready for measurement, gaily dyed rope decorations swing in the breeze, the mirrors and the pots and pans catch the sun, and piles of cloth compete with each other for attractiveness everything is bright and colourful and noisy, and the mixture is smells is amazing! Shuttered But today there is no bazaar and the village is on normal working duty. It looks very brown and drab, particularly in contrast with the clothes of the villagers. This is partly caused by dust, but mainly because the building materials are mud bricks. Mischievous But the children of the village were a constant delight. They never tired of the cars. On every occasion that we entered the village they would pursue us, screaming with excitement; when we stopped they would crowd around, hands out for the boiled sweets and mints that we carried. But apart from the crowds that followed the cars, children are everywhere. Small boys play in the dust, naked except for a silver chain around the waist (this is the earliest gift, at the time of name-giving, and is always worn when older, around the neck), little girls, giggling behind their sistersí skirts, eyes round and shining their pixie-like faces have not yet attained the near-classical serenity that comes with maturity to the women of India: when young, and excited, the girls look like mischievous monkeys. Babies in their sistersí arms ogle you solemnly from eyes ringed with black paste in the manner unfortunately so common in India. The schoolboys wear a uniform of white shirt and khaki shorts, with white khaki. Caps (as worn by leaders of the Congress Party), but without shoes. It is extremely difficult to judge their age. A boy guessed as nine will frequently be 14; undernourishment is all too common, but also the stock tends to be slight and wiry. The young girls wear blouses and skirts, Western style and very colourful, their hair is tightly scraped back into plaits and on the way to school they carry large slates and look very serious. At 13 they begin to wear blue saris over the white chotis or short bolero blouses, and suddenly achieve all the dignity and grace of their mothers and sisters, and inherit the beauty of movement characteristic of women who can carry two brass jars full of water on their heads and a baby on their hip with no suggestion of instability. Love mark They smile shyly, but laugh easily and delightedly, the dark serious eyes suddenly bubbling: their long plaits are woven with flowers or fern, and many coloured bangles glitter on their wrists. On their foreheads is the love mark, a red spot, or tear-shaped mark. All the little girls wear these as a general sign of family affection, but in girls of 15, 16 and 17 it may have reverted to the traditional meaning, that is of a specific loved-one, namely a fiance. In India marriages are still arranged, but they will proudly tell you that the system is much relaxed "nowadays we see our wives before marriage." At

first sight it appears that the whole village is built on this one street, but

in fact it spreads out over a rough circle. The back lanes are narrow, dirty and

rutted; here are the meanest huts and the lowest castes, the potters, the rope-makers

here the huts are interspersed with tiny dusty paddocks for small animals and

fowl and there are many low trees. It reminded me of a bunched up allotment area on a hot, lazy summerís day, but with pigs and hens largely replacing the flowers and vegetables adjacent to the potting shed - and with the important exception that here it was no potting shed, it was the living place of a whole family. Not big enough On the fringe of the village are the schools, primary and secondary. These are in stone buildings built by the villagers, and they are very proud of them. Equipment is very scarce. The junior children sit on the floor as they recite their lessons, and all articles for demonstration, wall-charts etc. are home-made. Also, the schools are far from big enough. Pusegaon High School serves 12 villages. In spite of education being compulsory up to 13, one frequently sees school-age children working in the fields. They even pass school waving cheerfully to their classmates. But until the schools are made large enough to hold all the pupils no action can possibly be taken by the authorities. CONTINUE TO OUR LIFE IN THE VILLAGE [ REPORT 8] © Malcolm T McKernan, 1960 Photographs © Tony Morrison | ||||||||

|

The

villages

The

villages

and

artificial pools, and in these, and in the river itself, people are washing their

clothes, their cattle and themselves. Scores of six-yard lengths of coloured sari

cloths lie parallel on the banks, drying in the hard bright sun, looking like

banners awaiting flying; in a pool on the right a bull is being manhandled and

a small boy washes its back; a truck has been driving into the river and its driver

is at work on it with a long brush; and wherever we looked men were washing themselves,

sometimes, quite comprehensively, making a form of privacy by their total disregard

of onlookers. And children were everywhere, some playing, some watching, some

just being. All of them were excited at our approach, none of them too shy to

crowd around the cars.

and

artificial pools, and in these, and in the river itself, people are washing their

clothes, their cattle and themselves. Scores of six-yard lengths of coloured sari

cloths lie parallel on the banks, drying in the hard bright sun, looking like

banners awaiting flying; in a pool on the right a bull is being manhandled and

a small boy washes its back; a truck has been driving into the river and its driver

is at work on it with a long brush; and wherever we looked men were washing themselves,

sometimes, quite comprehensively, making a form of privacy by their total disregard

of onlookers. And children were everywhere, some playing, some watching, some

just being. All of them were excited at our approach, none of them too shy to

crowd around the cars.