University

of Bristol Trans-Continental Expedition 1960 — 61 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Published Tuesday November 29th 1960 | ||||||||

Well, we never expected that our good luck would last for ever! So far we had kept good time. But that was Europe; ahead lay the Middle East and Asia. And there we disembarked. Our original plans had included a journey of great historical interest around Iraq, the Lebanon, Syria, etc. but this had to be revised regrettably, in the hurry to reach our work in India. So our route lay straight across Turkey, through the centre of Iran into Afghanistan and down into Pakistan. One leaves Istanbul along the coast of the Sea of Marmora, a very impressive run. Across the bay of dark water are the enclosing hills with the haziness of early morning obscuring their details. They appear to climb straight out of the water and this, combined with their mysterious vagueness, gives a feeling of northern mountains, th Isles of Scotland. And then across the highlands to Ankara. Created capital This is a "created capital" and lacks the historical fascination of Istanbul. It is built on and among several excessively steep hills - steeper than Park Street! Its chief beauty is at night when the Turkish passion for electric light fills the city valley with flickering patterns of different colours and intensities. The countryside of Eastern Turkey is very beautiful, though not in our conventional northern sense. The contours are those of rolling down-land skirted by low swirling hills looking like overgrown sand-dunes. Grain stubble diffuses a golden glow and through this strike the reds and browns of the earth. The hills are completely smooth. Often there is not a tree in sight, just the rolling hills in their subtle varieties of shads, speckled with herds of black and brown cattle, black and white goats and sheep. Where rocks show through, purples and greys are added in a marble pattern and in the distance the mountains frame the scene. Set against these hills, and almost camouflaged into them, are the villages of mud and dung-covered huts. Flat toped and closel grouped together they look like something straight out of "Beau Geste" - on expects to see Legionaires on guard. Overhead circle buzzards and kestrels. Most photogenic Down in the watered valleys the trees have the fresh tints of an English spring and there is a rich green groundcrop of the alfalfa type. Then up into the mountains high above massive gorges with the sheer rock faces and sudden drops. Epithets are thrown about …Grand Canyon country …Chinese Wall …Tibet … etc. This is undoubtedly our mot photogenic day - except that a photograph could hardly do justice to this type of landscape, the colour gradations are too subtle, the shapes difficult to define. As we drive into the evening the bases of the mountains become bluer and their peaks are caught in the pink light of the low sun. No one could imagine a more complete scene - beauty, serenity and strength; and, in the winter, I am sure, power and danger. Object lesson In the mist and clouds, 6,000ft. up in the pass, we met a New Zealander who was driving alone back to his home. His schedule was very austere, eating a minimum of food and sleeping in the car with his sheath knife handy. Later we heard more of him. We was refused the southerly route through Afghanistan - lack of a cholera certificate - and mistrusting the northerly track which is considered unsuitable for cars, had plunged into the unmapped centre of the country. He eventually emerged the other side - having spent many sleepless night alone in his car - ready to defend himself against numerous unknown horrors and dangers - with nerves in shreds and having no idea of the passage of days. An object less to would-be solo travellers. The next night we camped near the Iranian border and in the morning woke to find ourselves overlooked by Mount Ararat. We had never seen a photograph of this famous mountain and were delighted to find that with its snow-capped peak and perfect symmetry it could pass as a model for all mountains. We were no driving east into the tailend of a cholera epidemic. Naturally we had been inoculated and vaccinated against almost everything and were carrying International Certificates of Vaccination. Without these it would have been quite impossible to get through. The epidemic had spread from Pakistan through south Afghanisatan into eastern Iran. The Iran-Afghanistan border was closed in the east-west direction. From Iran onwards we were compelled to produce the certificates four or five times a day - often to people unable to read a word! We had passed through the thousand-odd miles of Turkey without mishap and negotiated the Turko-Iranian customs without trouble. All we were asked for was firearms - "Bang, bang," said the officer, pointing into the air; being assured we carried none he had little further interest. Then came Iran. Dust and ridges Immediately the roads settled down to the conditions were to recognise and suffer during the next two weeks and dream about for much longer. They are covered in dust - and soon so is everything else! The car ahead appears as though rocket-propelled, and the safest driving distance is about a mile apart. This cannot apply to incoming traffic, of course. Every time something passes the world goes grey for several minutes. The taste is terrible. We carry canvas water bags and drink pints per day - water that must be carefully and laboriously boiled and chlorinated. But worse than the dust is the vibration. These roads consist of a succession of ridges at right-angles to the direction of travel. They say this was caused by the wheels of the heavy lorries, but sometimes it seems it must have been deliberate; how else could it be so uniform - and so uniformly unpleasant? The correct technique is to skim the surface at speed, but since the road frequently drops four feet into the dry bed of a stream this is much too dangerous. Consequently the vehicles shudder and bounce along; the drivers fight the wheel, which seems alive, and think morosely of our delicate electrical apparatus and cameras which will soon be as good as dead. Things happen The roads are often reasonably staight, a fortunate circumstance since the cars frequently travel crab-fashion for considerable periods and maintaining direction in a straight line is difficult enough. When the driving wheel is turned anything can happen. Even the slightest bend becomes and adventure. Under these circumstances for day after day with heavily loaded vehicles something had to collapse. In fact, two things did - the rear shock-absorbers of one of the vehicles. So we limped into Teheran. We saw little of this cty, spending most of our time in repair work - trying to achieve an equitable distribution of shock-absorbers between the two cars.

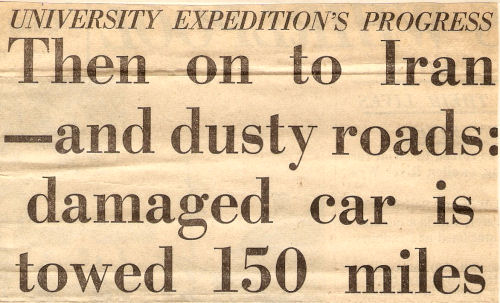

The next day we crossed our first desert - the Great Salt Desert of Khorassan - and saw our first snake. Fortunately its main desire was to get away from us! And today, also, we lost another shock-absorber! But then we had a stroke of good fortune. We called at the camp of an American pipe-laying company outside Shahrud for water, and they put us up for two whole days while we worked on the suspension of the cars. They also gave us the services of an expert welder. In return our doctor was able to perform a small operation on one of their men who had badly gashed his arm in a fan-belt. This was some slight return for their typically warm hospitality. Near Mount Damarvand 5670 m in the Alborz / Elberz rang bordering the southern shore of the Caspian Sea - Roger and Peter

Sheer bad luck

There was nothing for it but to tow. Over those dreadful roads we towed our second vehicle 150 miles to the town of Mashad. It took the equivalent of a whole day to do it and is some reflection on the strength of the cars that it was possible - after all one wouldn't feel kindly disposed to towing a vehicle from Bristol to London and further, and that on good English road! The driver of the second vehicle was in a dreadful position; tied fifteen yards behind the first car when he would prefer to be fifteen hundred, choked and blinded by the dust, and unable to do much to control his powerless vehicle which slid and leaped and rattled, seeking out all the worst bumps.

Radio link to Mashad But we reached Mashad, Mr Merlin Jones (from Cardiff), the British Council Representative there, was very kind; and although looking after homeless nationals is no part of the work of the Council, allowed us to camp in the grounds of the house. He also gave us invaluable assistance in arranging for a replacement radiator to be sent from Tehran. There is only one connection between Mashad - the third largest city in Iran - with Tehran, its capital; that is a radio-link, naturally in great demand. One gentleman had been trying to contact his office in Tehran for three whole days, and this was not considered exceptional. By badgering the manager we managed this difficult feat in one day. Then we had to wait another three to receive the replacement sent by train. Mashad is a holy city, full of pilgrims, with muezzins calling prayers many times a day. So we had an interesting, although frustrating, time. Out in a hurry Then we were out on those roads again. And, incredibly within 40 miles the bolt in a suspension component sheered fracturing a bracket, and one of the cars was on three wheels! These things can happen; one thing we were very thankful for, however was the relative absence of punctures. A recent Expedition had 17 on this stretch - we had only four, a tribute to the gentleness of the suspension. So we removed the offending bracket, returned to Mashad - which by now we knew quite well - and persuaded a young Iranian to weld a new part. Each time into and out of Mashad we were inspected at a Cholera Check Post - we thought they would begin to recognise our faces. By noon the following day the repair was completed and we hurried out of Iran as fast as we dared; 1,400 miles had taken us 14 days. Iran

was unlucky; and ahead lay Afghanistan. But we pushed on happily still having

confidence in our cars - even in their now sub-standard condition. | ||||||||

|

We

never expected...

We

never expected... Shortly

after leaving Tehran we discovered another hazard; this was the almost total lack

of signposts - even in Persian, which would have been virtually useless anyway.

So we made our first wrong turning and were rewarded by seeing accidentally Iran's

highest mountain - Damavand, 19,000 ft.

Shortly

after leaving Tehran we discovered another hazard; this was the almost total lack

of signposts - even in Persian, which would have been virtually useless anyway.

So we made our first wrong turning and were rewarded by seeing accidentally Iran's

highest mountain - Damavand, 19,000 ft. Now

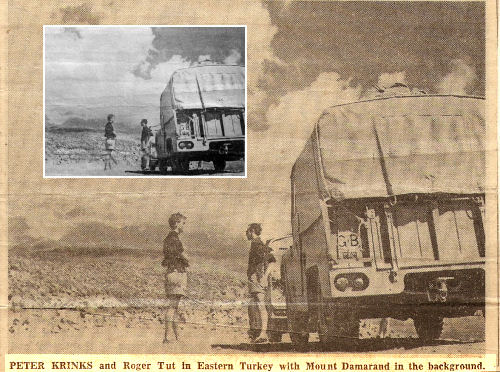

four days late we pressed on as quickly as the roads would allow. But again disaster!

This time a piece of sheer bad luck. A stone jumped up from the road and bent

a blade of the fan, this turned into the radiator and tore a deep circular hole

in it. Inside seconds all the water drained away and we were left high and very

dry well over a hundred miles from civilisation.

Now

four days late we pressed on as quickly as the roads would allow. But again disaster!

This time a piece of sheer bad luck. A stone jumped up from the road and bent

a blade of the fan, this turned into the radiator and tore a deep circular hole

in it. Inside seconds all the water drained away and we were left high and very

dry well over a hundred miles from civilisation.