University

of Bristol Trans-Continental Expedition 1960 — 61 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| published Thursday October 6th 1960 | ||||||||

Here is their first progress report, written as they journeyed overland to India, driving their own vehicles and sleeping in tents. The report comes from MALCOLM McKERNAN leader of the expedition and the society's public relations officer.

Out of England in one day Out of England in one day (from Council House to Customs shed)… through France in a day … across Germany in a day… and Austria. All these places we had long desired to visit. All were hurried through with scarcely a regretful thought.` Travelling at speed emphasises the contrasts of the surroundings, but it also picks out strange similarities. For example, we have had three police escorts. One was in Bristol, by kind permission of the Chief Constable. Another was out of Alexandropolis, in Greece. Because we could not read the signposts or establish contact in English, French German or Italian, the Greek patrolman rode with us on an American motor-cycle - rather like Highway Patrol, but without the siren. The third escort was in Maku in Iran, and was a police sergeant riding his own bicycle. Yet the stateliness of this procession was perhaps more impressive than the greater efficiency of the others. This policeman, in his musical-comedy royal blue uniform, with gold stripes and enormous gilt badges, was escorting us to a petrol station - and incidentally preparing to "oblige us" by exchanging Turkish money for Iranian. Hazards of travelling are many. The greatest are the dangers of insect bites and the possibilities of road accidents. The latter vary, of course, from country to country and often depend upon the road surface. The fast roads are not necessarily immune. On an autobahn it is almost more important to look behind than in front, for the overtaking car on your tail may well be doing 100 m.p.h. If you pull out in front of him, he can't stop. Greatest concern On the dust tracks one can hardly go fast enough to have a serious accident, but equally it may become impossible to go straight enough to avoid a minor one. Under bad conditions the behaviour of the other road users is one's greatest concern. We discovered this while grimly negotiating a mountainous detour in Turkey. A hazard far worse than that offered by the road surface was the standard of driving among the local bus drivers - and there are a lot of buses. Perhaps their schedules are impossibly tight (no revision in spite of the detour?), but they give the impression of being joined in a universal suicide pact. To be behind them is bad enough; their enormous tyres throw up impenetrable clouds of grey dust into which the huge, gaping exhaust pipes emit filthy black smoke, London has nothing on this! One all-too-frequently is behind them because their technique is never circumscribed by the bounds of safety. They possess horns as powerful as their engines and give both free play. Madman's leapfrog One hears the klaxon and on they come - neither the desires of the preceding driver, nor the particular circumstances, in any way influence them. It is commonplace to see them overtaking each other on hairpin bends enveloped in obscuring dust, with their offside tyres within a couple of feet of a terrible drop. On they go, taking and overtaking - blue first, now red, playing at madman's leapfrog. The memory of their horns remains, a mixture of an urgent foghorn with a diesel locomotive hooter, overlaid with a mournful howl like the Hound of the Baskervilles. Incongruous The greatest contrasts are in road conditions and methods of transport. These can present incongruous pictures. As on a German autobahn, where two lines of super-modern cars and strings of high-tension cables were passing under a bridge over which was passing an oxcart. The autobahns carve their way across valleys and through forests with complete impartiality. They are densely populated, with lorries and trailers as well as private cars. These lorries are enormous and the trailers equally so, each equivalent in size to an old pantechnichon. They have three drivers and the cab is equipped with a bed for the man not on duty. The ox-carts, naturally, are restricted to the secondary roads. So are the horse-drawn carts, of which there are a great number. These horses are an engaging sight - they wear hats! They are ear-muffs, presumably for protection against flies and they take the form of two neat ear caps attached to a small skull cap. There is considerable variety in these garments. Sometimes they are of plain material, and the horse has a straight-forward, no-nonsense, working appearance. But other owners show greater originality and use meshed material which looks like coloured string dishcloths. Wearing, say, two blue ear-caps attached to a red dishcloth, a horse can look surprisingly frivolous even when pulling an ordinary, unpainted cart.

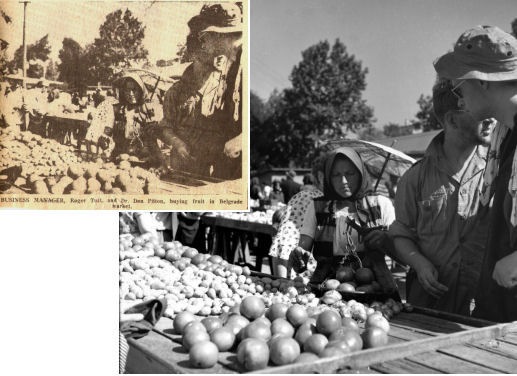

From Yugoslavia onwards oxcarts drawn by two or sometimes four oxen are a common means of transportation. They must be the slowest in the world, but have tremendous power. They frequently have to take their loads up or down a ten foot drop on to the "major" roads. This they do in a great rush - the bells jangle, the cart judders and groans, the driver shouts - then the dust settles and the equipage is proceeding along its normal placid way as though something else had achieved the feat and caused all the commotion. Right - Roger and Don in a market in Belgrade, Yugoslavia Personal transport is very varied. Horses and carts are used, landaus in some Yugoslav, Greek and Turkish cities. In the country it is the donkey. The riders perch on the rump of these animals in a position clearly impossible to maintain yet not showing the slightest signs of falling off even at full gallop down the dusty tracks. And of course in Turkey we saw our first camel. Some members of the team were quite satisfied and could have returned home there and then! The camel's walk has a strange rhythm, to watch the rider only, one would think the animal was proceeding using dance steps - forward, side, together. So snooty Watching the whole performance the animal's dignity (self believed) is seen, and from certain angles this remarkable beast takes on a pre-historic air, caused by the carriage of the long neck and the humped back. Perhaps their air of antiquity gives them the right to be so snooty. We found Yugoslavia extremely interesting and often unusual. Our entry to Zagreb was down a wide, tree-lined road. In each of the gutters ran the tram service, a sensible method of ensuring that passengers do not alight in the middle of the road. But what of the slow traffic? Cyclists hate tramlines. This problem has been solved by sending the cyclists, scooters, handcarts and so on in their two streams down the CENTRE of the road, and forcing the more powerful vehicles to negotiate the tramlines and gutters. This is all very well, but when a cyclist wishes to go into a shop he has no alternative but to park his machine in the very centre and skip across. Colourless We had difficulty with another, and much longer stretch of road in Yugoslavia. We can report that in a couple of years the road system will be among the best in Europe; and we were in at its birth, so to speak. We travelled miles of half-made modern, or genuinely ancient, roads with loose surfaces. The countryside is all colourless. It seems to have given up in the fact of the onslaught of the dust. We drove through old villages with many small houses that cluster together as though for protection, giving a feeling of an ancient community. One almost expects to find the village barricaded against the marauders of the night. The vehicles jog and jolt through and the dust settles everywhere. Even under these trying conditions the people seem perfectly happy and friendly, and they and their houses are unbelievably neat and clean. This day's journey extended into the night, a practice we try to avoid. Through small towns with lights in barbers' shops and a few neon signs that looked incongruous in Yugoslavian script, as though some of the tubes had broken and fallen into incorrect angles to make them incomprehensible - a state of affairs not unknown in England. Challenge met As darkness fell, the road was travelling evidence of its own impending construction. Piles of gravel and sand at the edges, heaps of beautifully cut stones for walling. Darkness, mountain passes and bad roads. But we had set ourselves a target and after a period of disgruntlement at the roads, the opposite effect developed in the team. We were determined that these handicaps should not be allowed to upset our plans. In the end the contest resulted in a draw between us and our surroundings, but we had kept reasonably close to our schedule and had learned a lot about the capability of our vehicles and ourselves. THOUGHT FOR TODAY. One of the last things we saw as we left Bristol was a large poster reading: "Next time go by Rail." | ||||||||

|

Towards

the end of August the University of Bristol Expeditions Society's Trans-Continental

Expedition (1960-61) left Bristol on a journey which is taking them to two main

regions of study - Central India and Bolivia.

Towards

the end of August the University of Bristol Expeditions Society's Trans-Continental

Expedition (1960-61) left Bristol on a journey which is taking them to two main

regions of study - Central India and Bolivia. Slow,

powerful

Slow,

powerful