University

of Bristol Trans-Continental Expedition 1960 — 61 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Published 1st February 1961 | ||||||||

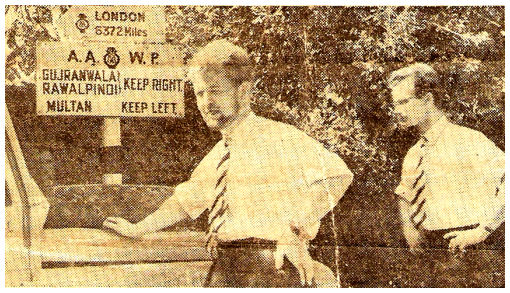

Pakistan is very unlike the Britain we left behind. In fact, it is much more like war-time Britain. Afghanistan, admittedly, had appeared to be a country in a state of preparedness, with armed soldiers swarming near the frontier and jet planes warmed up on the airstrips; but Pakistan gives the impression of a country under siege. Immediately inside the frontier is the Khyber Pass. It is all in Pakistan - and it is a formidable obstacle. What are one's expectations of this famous landmark? Very vague in most people, I imagine; having put aside childhood phantasies of rocky defiles and betopeed soldiers being spied upon by lurking tribesmen, it is difficult t visualise an alternative picture. Since it is the way of adults to over-compensate for the exuberant imagination of their childhood, most people would say, resignedly; "It's probably more like a moor than a gorge." Well, perhaps it is; yet it still succeeds in being impressive. It is quite wide, of course - after all, armies used to march through it - and the walls are not precipitous. Incongruous But the road has to be quite tenacious to hang on to the sides and it performs all the convolutions one would expect as it doubles around military pill-boxes cut out of the rock face or plunges into short tunnels, rattling over the pits dug for land mines. Down in the valley there is the occasional incongruous sight of a flourishing farm with its terraced and irrigated lands. Incongruous, because the whole area is given over to military preparations. It is impossible to proceed through it without using the road, since from wall to wall the valley is illed with succeeding waves of concrete anti-tank teeth and rolls of barbd wire. Itreminds one of the beaches of Britain during the war, but in its concentration is even more depressing. The emphasis on military power in such countries as Greece (to a smaller extent), Turkey, Afghanistan and Pakistan has been the most saddening feature of this journey. Isolation In the Khyber photography is strictly forbidden, there is the constant feeling of being watched - and this time not by wild tribesmen, but by the citizens of the British Commonwealth; and Shagai Fort, a few miles into the pass, must surely house tens of thousands of troops. So we were glad to leve this gloomy prospect behind. But we couldn't escape from the feeling of tension. Pakistan is a poor country and an isolated one. She has borders with Afghanistan, Russia and China, through the disputed territory of Jammu, and India, all of whom she considers hostile; only Iran in the West is not so regarded. The newspapers are full of accounts of the intrusions of Afghan tribesmen and the activities of the Indians in their half of Kashmir. Also of the necessity to promote friendly relations with the new African States. One feels that any offer of friendship would be welcomed; yet one that has been received - of help with armaments from America - has bred greater suspicion in Pakistan's neighbours No doubt Pakistan is the largest Muslim State in the world and this is emphasised for its solidifying effect and perhaps this breeds a certain intractability in its politics. "We are not a 'neutralist State,'" declared President Ayub Khan. "There can be no doubt as to where we stand on the question of Communism." Field Marshal (then general) Ayub Khan took over the Government in 1958 in order to fight corruption and inefficiency; Pakistan had shown she was not ready for full democracy, he declared; he would restore democracy, but "of a type that the people can understand and work." He has introduced a system called the "Basic Democracies." In this manner it is hoped gradually to bring the country3to a realisation of the responsibilities of full democracy. Dark hints Meanwhile, an 11-member commission has been appointed to "frame constitutional proposals for the establishment of democracy, the consolidation of national unity, and a firm and stable Government." And across the border Indians, from the moral superiority of their own positions with an elected Government, hint darkly about the dangers of military dictatorship. There is a strong nationalistic feeling prompted both by international "incidents" and by internal propaganda. Sometimes it seems that they are trying to convince themselves. Probably this is realised, for Ayub Khan said recently; "We must work more and talk less." Exhortations This verbal emphasis on hard work is echoed at the Bata shoe factory. The boundary wall - at least 100 yards long - is painted white and covered with a string of red slogans: "Every day contains 86,400 seconds"; "More speech, more quarrels"; "An ambitious wife, a hard-working husband," and other philosophical gems straight out of a Western sales director's exhortation to his staff. Our stay in Pakistan was not a long one, so most of our views on the country are based on quick impressions. Crossing the Indus river, for example. We did this not by day, as the photographers had hoped, but more romantically by night - in fact, under the largest, most yellow, moon I can remember. The bridge of great strategic importance, is entered through a guardroom; armed soldiers examine your credentials. The bridge is closed to commercial vehicles at dusk; a great iron reinforced door opens to allow access and closes behind the cars. Agreement

Some of the cities of Pakistan have a strong English feeling - as of a prosperous country town. Peshawar was one, exceedingly neat and tidy with plenty of shade from tall trees. A great contributor to the "At home" feeling was a 1934 Baby Austin happily bowling down the road (just like any English university town!) We found Lahore in a state of great jubilation having just welcomed home the victorious Pakistani Olympic hockey team - its success having been made all the sweeter since it was over India , who had held the title for something like 32 years. Here we delivered a letter of greeting from the Lord Mayor of Bristdol Ald. A. Hugh Jenkins, to Mr Massood, the chairman of the Municipal Committee. Memories Under the new regime Mr Massood is an appointed administrator, an ex-Army officer who had been though Dunkirk and served in Africa with the British forces. He had many memories of England and was very interested to hear of life and conditions there now. We also made the very English the very English pilgrimage to see Kim's gun and visited the Civil Military Gazette which Kipling had once edited. | ||||||||

|

Pakistan

Pakistan

Underneath

flow the waters of the Indus, essential for irrigation intwo countries. But you

cannot lock up a river and to everyone's relief an agreement was reached last

September in thelatest of many attempts to solve this bitter proble.

Underneath

flow the waters of the Indus, essential for irrigation intwo countries. But you

cannot lock up a river and to everyone's relief an agreement was reached last

September in thelatest of many attempts to solve this bitter proble.