University

of Bristol Trans-Continental Expedition 1960 — 61 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Published on 17th February 1961 | ||||||||

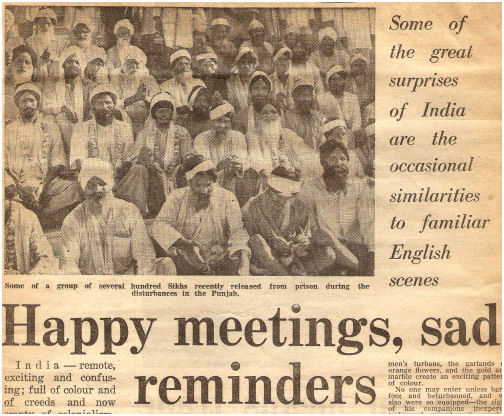

India - remote, exciting and confusing; full of colour and of creeds and now empty of colonialism. So for us today India is double interesting, a new country with an ancient history. All previous knowledge of the country - from books or at first or second-hand from travellers - has emphasised the differences between the East and the West, the romantic and unexpected aspects of Indian life. So it is for strangeness that the traveller looks. And, of course, he finds it. The colours and the contrasts, the differences in life and beliefs are duly noted and some personal meaning extracted from them. Due to this conditioned approach some of the greatest surprises are caused by the occasional similarities that one stumbles upon. Like home After passing through a typical Indian village with its huts straggling along the road, its small tea-houses roofed with banana and palm leaves, the fruit and vegetable sellers squatting on the ground with their goods, the naked children playing, the women washing saris in the stream with scores of five-yards lengths of coloured cloth drying on the rocks and pebbles - after commenting on this, and perhaps taking a few photographs, you could drive out of the village on to a road that might be in rural England. Everything green; green English-looking trees by the roadside and out on the hills; pastureland, sometimes with smaller bushes and shrubs like a parkland scene; even the crops could be English if not examined too closely. And over the trees in the distance is a tower like that of a country church. You stop and wonder about it. Then suddenly a monkey drops from a nearby tree, or a green and red parakeet swoops across the road, and the mood is broken. It is not England. But nevertheless, an important point has been made; it is the same world and perhaps looking for differences is not the most rewarding approach to it. Hazardous Our route through India missed all the beauties and grandeur of the northern states such as Kashmir. We travelled through Amritsar and Delhi, to Indore and over the Western Ghats to the coast and Bombay. The great hazards on the roads are the carts and the animals. India has the largest animal population in the world, our geographer tells us, and none of us would dream of doubting him. After a few hundred miles of Indian main roads, a motorist would not only agree but insist that they had all appeared in front of his wheels. They come in all shapes and sizes and most colours; they are hitched to cars, are led in twos and threes, wander entirely on their own, and are driven in large herds; there are sheep and goats (very aristocratic, with high bridged noses down which they peer rather like camels), water buffalo and, of course, cows. The cow is an important religious symbol and it may not be killed, or even, in theory, ill-treated. An unbiased observer would swear that they appreciate this and abuse the privilege, their road manners being careless to the point of suicide. These are "zebu" cattle with the high hump on the shoulders, very strong and disease-resistant; they are fine-looking animals (on the rare occasion when sufficiently well fed) and are beautifully coloured in white, creams and fawns. Brainless But a greater nightmare to the motorists is the water buffalo, who appears to be totally brainless. He is not very tall, but is exceedingly solid and heavy - they say you can hit one full-on at a respectable speed and emerge from the wreckage of your car to find the animal blinking placidly down on you. They lunge along with the head craned forward, the ears lying flat, and the long, slightly curved horns flatter still; this gives them a permanent injured expression and it gets very monotonous. Looking at them it is easy to see where the expression "cowed" comes from. Our first Indian city was Amritsar, the city of the Sikhs. It was also our introduction to one of the two greatest problems in India - the many different languages and cultures of its varied people. (The other, of course, is that of population which we will come to later). The

Indian Government, in an attempt to integrate the country and create a feeling

of one nationality has decreed that there shall be But this also means that it must replace the regional languages, and this is not popular - to the southern Indian, such as the Tamil, Hindi is considered a foreign language (perhaps even more than English) and one that must be learned. Fearing that their ancient languages and cultures will be swamped, the people are demanding that the States should be decided on a language basis. Difficulties Last May, Bombay State was divided into Maharashtra and Gujerat states, where the people are Marathis and Gujerathis and speak those languages. Hence in the schools of Maharashtra, Marathi is taught, then Hindi, and then English; this makes difficulties for the student who wishes for further education since the use of English text books would then be essential. The Sikhs of the Punjab are now demonstrating for a reorganisation of their state and the use of Punjabi as its language. They are using the method of non co-operation and courting arrest which was used with such devastating effect by Mahatma Gandhi[s followers during the time of the British Raj. This weapon is proving just as awkward when used against their fellow-countrymen. We saw such a demonstration in Amritsar. Thousands of turbaned Sikhs - women and children included - were parading through the streets of their holy city, shouting, capering and singing slogans. At that time 41,770 had been arrested, by now it must be many more. Just recently their religious leader, Sant Fateh Singh, was with difficulty persuaded to break an avowed fast-unto-death on this question; it is reported that he is still unsatisfied with the Governmental negotiations, and there is a danger that he may recommence his fast. Dispassionate Amritsar has a history of turmoil. We were firmly, although politely, taken to the Jallian Walla Bagh where in 1919 Brig.-Gen. Dyer, A total of 1,650 rounds were fired, 379 people were killed and 1,137 wounded; 1,516 casualties for 1,650 shots - a record of the tragic vulnerability of the crowd rather than the accuracy of markmanship. Our guide was remarkably dispassionate in recounting the terror and futility of the victims, and in no way appeared to link us with it - for which we were very grateful. However, the once disused area is now being turned into a public ground with a memorial to the martyrs in the form of a flame carved out of a blood red stone. Perhaps the occurrence may be forgiven, but it can never be forgotten when such a memorial remains. Using the ills of the past to inculcate a feeling of unity in the present is one of the more distressing tendencies in newly independent countries. Altogether the reinforced reminder of the old bad days was an unfortunate introduction to the new India. No idols The following day was happier. We were shown round the Golden Temple of Amritsar, the holiest of Sikh temples. Sikhism was founded in the 15th century. The Sikhs believe in one God - "He is the truth. Evermore shall truth prevail". They use no idols, only a religious book, the Grant Sahib, which is unique since it also incorporates writings of Hindu and Muslim saints. They have been made into a community by certain outward signs, such as never cutting the hair or the beard and always wearing a turban. The men have one surname Singh (Lion) and the women one prefix, Kaur (Princess). Their religion is based on love, self-sacrifice and self-denial (no tobacco or alcohol), but they also hold that goodness and truth are worth fighting for. The Golden Temple is a remarkable building. It is a large compound with four doors (indicating that people may enter from any direction, faith or creed); inside this is a small rectangular lake of holy water in which ablutions are performed; set in this, and approached by a causeway is the temple itself. It is decorated with gold and with beautiful mosaics and patterns in marble and semi-precious stones, it gleams in the sun and casts glittering reflections in the surrounding water. The building is not very large, the system of worship being to visit rather than to remain. Cash gifts Religious music is performed continuously and the Grant Sahib is read; the Sikhs make donations of money (at least one tenth of the income), and give flowers for which they receive in return flowers that have been blessed. There is a very great feeling of life and warmth; women worship with the men (a rarity in Eastern religions), and their saris, the men's turbans, the garlands of orange flowers, and the gold and marble create an exciting pattern of colour. No one may enter unless barefoot and be-turbanned, and we also were so equipped - the sight of his companions inexpertly turbaned caused each member of the expedition great amusement (and opportunity for photography!), and this amusement was echoed with great good humour by the crowd. This is a place where religion seems to be alive; at the height of the season it is not extraordinary for 10,000 people to come here in a day. We spent the night in a room in the temple - they are forbidden to turn away any suppliant - and were most impressed by the teachings of the religion and by the people themselves who are extremely clean in appearance and seem dignified and gentle. This being the case we were astonished to find that in no other part of India could we find anyone to say a good word for the local Sikhs. Prejudice In Bombay, where many migrated after the division of the Punjab, the population regards them as an undesirable community clique, very rapacious and forward in all shady dealings; the fact that one never sees a Sikh begging seems to tell heavily against them rather than be a point in their favour. Sikhs make good mechanics, and the current scornful remark is to contend that they are fit for nothing but lorry-driving. This reminded us of the type of community prejudice that we have known only too well in England and Europe, and, without wishing to take any sides, we were unhappy to see it in India. By contrast our next stop was at the Taj Mahal at Agra. (We had passed quickly through New Delhi with no time to see very much - except that we were most impressed with the United Kingdom High Commission building, a fine and dignified piece of modern architecture.) The Taj Mahal was built in the 17th century by Shah Jehan as a mausoleum for his favourite wife; it now contains both her body and his. Made of white marble with dome and minarets, its proportions are so excellent that the size cannot be appreciated except at close quarters. Then the size and simplicity are awe-inspiring and the beauty of the marble carvings and the delicate floral patterns of inlaid coloured stones are most moving. Remoteness But its perfection is perhaps a little inhuman. Set on a wide terrace of white stone, with the river behind and below, in the bright sunlight it seems to float above the earth as though not really a part of it. Compared as a religious building with the Sikhs' temple, with it's warmth of colour and humanity, the Taj Mahal is cold and remote. But this is a memorial to a great love, and perhaps it is fitting that it should convey this feeling of purity and the impression of wishing to rise from earth to heaven. Then we had a long all-night drive from Indore down over the steep Western Ghats to the coastal plain and Bombay. All that remains with us of that drive is a confused memory of trees in the darkness and innumerable hair-pin bends; and, as the dawn turned into day, the relentlessly mounting heat and humidity. In fact Bombay was not terribly hot - 85 degrees - but the humidity of that first day was 95 per cent. Bombay begins 23 miles from the coast and there is only one way in or out - a road so congested that it is easy to believe that half the world's animal population, most of its carts, vans, buses and trishaws, and all too many of its people, are there with you. In the city, this impression is continued; by day it is literally filled with people - thousands upon thousands of white-clad men, this monotony relieved by the coloured saris of the women; and at night the pavements are so full of sleeping figures that one must walk in the roads. This is a city in which the cliché "teeming millions" really takes on a meaning.

| ||||||||

|

India

- remote, exciting and confusing

India

- remote, exciting and confusing